Aeolus: Weather forecasts start using space laser data

- Published

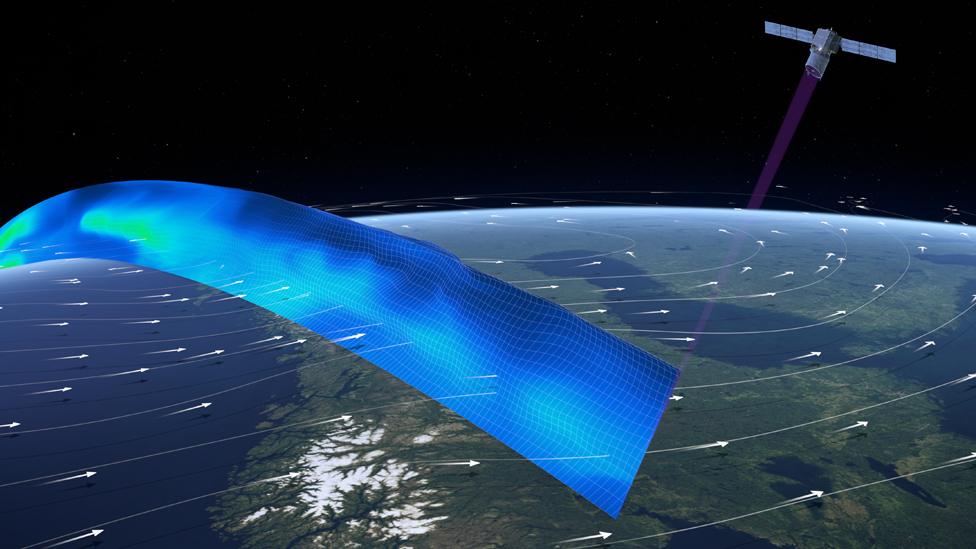

Artwork: Aeolus circles the Earth at an altitude of 320km

Europe's novel wind-measuring satellite, Aeolus, has reached a key milestone in its mission.

The space laser's data is now being used in operational weather forecasts.

Aeolus monitors the wind by firing an ultraviolet beam down into the atmosphere and catching the light's reflection as it scatters off molecules and particles carried along in the air.

The European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts says the information is now robust enough for routine use.

The Reading, UK-based organisation is ingesting the data into its numerical models that look from one to several days ahead.

Forecast improvements are most apparent for the tropics and the Southern Hemisphere.

Meteorologists are constantly trying to increase their skill level; they want to see a certain performance being achieved further and further into the future.

And on one important measure - the eight-day look-ahead - the ECMWF says the Aeolus data enables conditions in the Southern Hemisphere to be forecast with the same level of accuracy an additional 3.7 hours into the future.

"This is just one experimental instrument but it suggests that if you had many more of them in space you would have an even greater impact," the centre's Dr Michael Rennie commented.

"Aeolus shows us there is a lot of promise from this type of direct wind measurement," he told BBC News.

More and better wind data has long been sought by meteorologists

The UK Met Office is likely to start ingesting Aeolus data routinely into its forecast models from the Summer. Meteo France and DWD (Germany) are expected to follow too. The Americans have also been running simulations to assess the benefits, and the Japanese are about to start. The Chinese have investigated the quality of the data through comparison with other satellite wind observations.

The European Space Agency's Aeolus satellite is regarded as a breakthrough concept.

Wind measurements have traditionally been very patchy.

You can get data from anemometers, weather balloons and aeroplanes - and even from satellites that infer air movements from the way clouds track across the sky or from how rough the sea surface appears at different locations.

But these are all limited indications that tell us what is happening in particular places or at particular heights.

Aeolus on the other hand gathers its wind data across the entire Earth, from the ground to the stratosphere (30km) above thick clouds.

How to measure the wind from space

Aeolus fires an ultraviolet laser through the atmosphere and measures the return signal using a large telescope

The light beam gets scattered back off air molecules and small particles moving in the wind at different altitudes

Meteorologists will adjust their numerical models to match the information gathered by the satellite, improving accuracy

The biggest impacts are expected in medium-range forecasts - those that look at weather conditions a few days hence

Aeolus is only a demonstration mission but it should blaze the trail for future operational weather satellites that use lasers

It's been a challenge getting the technology to work. For a long time, Europe's engineers struggled to find a design for the UV laser instrument that would work in space.

And when the satellite finally launched to orbit in 2018, it did so 19 years after first approval.

So to see Aeolus working - and working well - is an enormous fillip to all the teams involved in the project's development.

It was, however, built as a one-off research mission and if the forecast benefits are to be maintained, Europe will have to consider a follow-on.

Those discussions have already started. At a meeting in Seville, Spain, in November, research ministers from the nations that make up the European Space Agency agreed to fund feasibility studies.

It's been suggested that two or three lasers might be flown in a constellation.

"Some of Esa's member states support starting preparatory activities for a potential follow-on mission," said Aeolus mission scientist, Dr Anne Grete Straume.

"Of course, we'd need to improve it and for the next generation there are a number of things we could make even better, such as the stability of the laser instrument. At the moment it looks good but for the future it would have to be absolutely solid," she told BBC News.

The Aeolus satellite was assembled from European components in the UK factory of Airbus

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external