Heirloom plants: Saving the nation's seeds from extinction

- Published

A young girl holds mangolds grown in Cornwall in the 1930s

The battle of the Somme in 1916. A British soldier fighting in France is given seeds as a memento of happier times. When he returns home, he plants them in the soil. His family and friends carry on the tradition, and, today, you can still find the Blackdown Blue pea growing somewhere in Somerset.

Catrina Fenton, head of the Heritage Seed Library in Coventry, rests the seeds in her hand. "People like to grow something that's got a bit of history behind it," she says. "A lot of the varieties in our collection have got wonderful stories; they relate to a particular place, or they taste a bit like the tomatoes their grandfather used to grow."

She shakes black and cream beans from another envelope on to her palm. Legend has it that seeds of the Brighstone bean were salvaged from a shipwreck off the Isle of Wight. "Nobody can quite agree what century that happened. But, because those seeds were then in the hands of the local population, they continued to grow them for generation after generation and therefore it's been associated with that particular place and time, which is really rather charming."

Giant cabbage shown at the Harrogate Show in 2017

Catrina has an encyclopaedic knowledge of the hundreds of curious-sounding vegetables that have been grown locally for centuries. The seeds of these heirloom, or heritage plants, are conserved at their facility near Ryton. Part seed library, part museum, part botanical garden, the organisation distributes seeds to members interested in helping to save local plants at risk of disappearing.

"The seeds that we're distributing to our members we know has been grown in the UK in UK-growing conditions," says Catrina. "And, of course, that's not necessarily the case for your standard packet of seeds. You might not know where they come from but the vast majority of seeds may well be imported from other countries and that provenance of where your seeds come from I think is as important as your food."

Named after Uncle Joe

When I visit early in the year, brown envelopes of seeds sit in pigeon holes waiting to be posted out to members. Black jack kale is lined up next to purple podded best, Ray's butter bean, giant stringless and parfree's dragon. The oldest variety in the collection, a kind of field bean, was first recorded in 1293. Others have connections with local places and people. "Their [true] names have got lost in the midst of time and they're now named after Uncle Bert or Aunty Madge or Uncle Joe or something like that," says Catrina.

Two young girls with a marrow grown at at allotment in Surrey in 1941

There's no strict definition of a heritage variety, but the plant must be pollinated naturally, with pollen spread from one plant to another by insects or the wind. In one of the polytunnels, the heads of leeks poke up out of the soil. Catrina explains how later in the year, a beautiful flower head will appear, which will be pollinated to produce seeds.

The seeds will carry the parents' genetic material, which will be passed faithfully down to future generations. In contrast, most commercial seeds are F1 hybrids deliberately created by crossing two different parent varieties. Saved seeds may not germinate and if they do, the new plants will not breed true. "A big important part of what we do is to make sure that we conserve by continuing to grow varieties that might otherwise be lost," explains Catrina.

The rise of seed swapping

You can still find a few heritage varieties on sale in supermarkets, such as little gem lettuce, which has been cultivated for more than a hundred years. Many, though, have disappeared from the shelves. Today, three companies control about half of all seeds grown on the planet, many of which are patented.

As a reaction against the increasing control of the supply of seeds by a handful of large companies, local seed swapping events have sprung up. The biggest such event is Seedy Sunday, which takes place in Brighton every year.

A prize leek from 1949

"The idea is to get people to grow and to keep their own seeds and to then swap their excess with other people," says Ros Loftin, who has been a committee member for 10 years. "When I started going to Seedy Sunday just to swap or to get some local seeds it was, shall we say, quite an alternative event, whereas now there seems to be quite a few youngsters who come, and families. They have a window box or they have a little bit of a back garden and they would like to grow some food or some flowers."

This year, she is growing no less than 32 varieties of heritage tomatoes at her two allotments. "I try and keep some of the old ones that date back to the 19th Century for historical reasons, and also for taste and colour," she says, pointing out that as well as saving varieties from the past that might otherwise no longer exist, heritage plants are important in a changing world. "The fact that the plants are different allows some degree of adaptable resistance to disease and stress," says Ros. "That's where the seed exchanges are important because they are local events. They bring back to the locality the different varieties that are adapted."

Catrina Fenton echoes her views. "We know anecdotally and also with our work looking at some of these varieties more specifically that they will have certain resistances and resiliencies, whether it's environmental or pests and diseases, that of course are going to be really important to us as a genetic resource particularly under the challenges of climate change, for example."

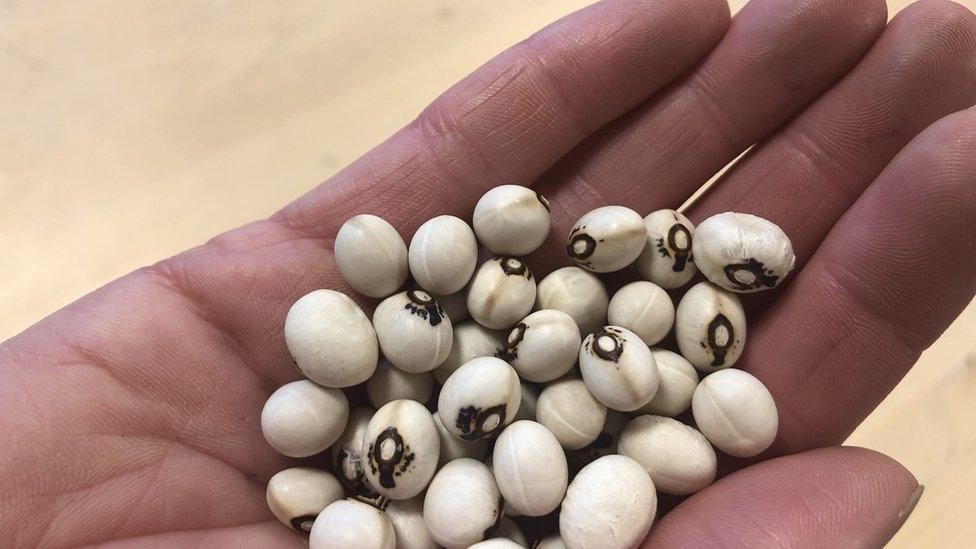

The markings on this seed give it the name - angel bean

Before I leave, I ask her a particularly tricky question. Which is her favourite variety in the collection? She settles on the angel bean, with its distinctive mottled seeds, which was traditionally eaten at Christmas time. "This an old German variety where they took the pods off, podded them around Christmas time - to reveal, with a little bit of imagination, a little angel on each of the seeds. There's a whole load of reasons why people save seeds, including how beautiful the seeds look."

Follow Helen on Twitter, external.