Mud wasps used to date Australia's aboriginal rock art

- Published

All the research has been conducted with the active participation of traditional owners

When the veteran telecoms engineer Damien Finch went on a three-week bush walk in Australia's Kimberley region, he became enthralled with its rock art.

On his return home, he tried to find out more about these enigmatic aboriginal paintings and engravings.

"I couldn't believe how little was known about them; we didn't even know how old they were," Damien said.

"It seemed disrespectful that scientists hadn't studied this stuff more; it was downplaying the importance of the culture," he told BBC News.

Now, 10 years on and in his 60s, Damien is putting that right.

He's approaching the end of his doctoral research on the topic, and in this week's Science Advances journal, external, has published his own efforts to age the Kimberley's so-called Gwion figures.

Watch a mud wasp build a nest and entomb its prey

These feature finely painted human forms, often in elaborate ceremonial dress and carrying spears and boomerangs.

It was thought they were painted some 16,000 years ago, but the University of Melbourne investigator has been able to show the likely age is nearer in time - at about 12,000 years ago.

Dating rock art is really hard. Aboriginal artists use iron oxide pigments (ochre) which contain no organic material and are therefore resistant to any radiocarbon analysis.

Damien has got around this by studying instead the scraps of organic matter stuck on top of and underneath the paintings.

And for this, he's working with wasps. In particular, the ones that build nests out of mud. There's a wide group of these.

Some will enclose their prey - such as a paralysed spider or caterpillar - inside an earthen box. Before sealing the lid, the wasps lay an egg on the unfortunate victim. The developing larva then consumes the immobile spider or caterpillar, eventually digging its way out of the nest as an adult to carry on the cycle.

From Damien's point of view, when the female wasp gathers her mud supplies she inevitably picks up fragments of charcoal from the Kimberley's fire-prone landscape. And this charcoal can be radiocarbon dated.

He's examined the remains or more than 20 ancient nests at various rock art sites.

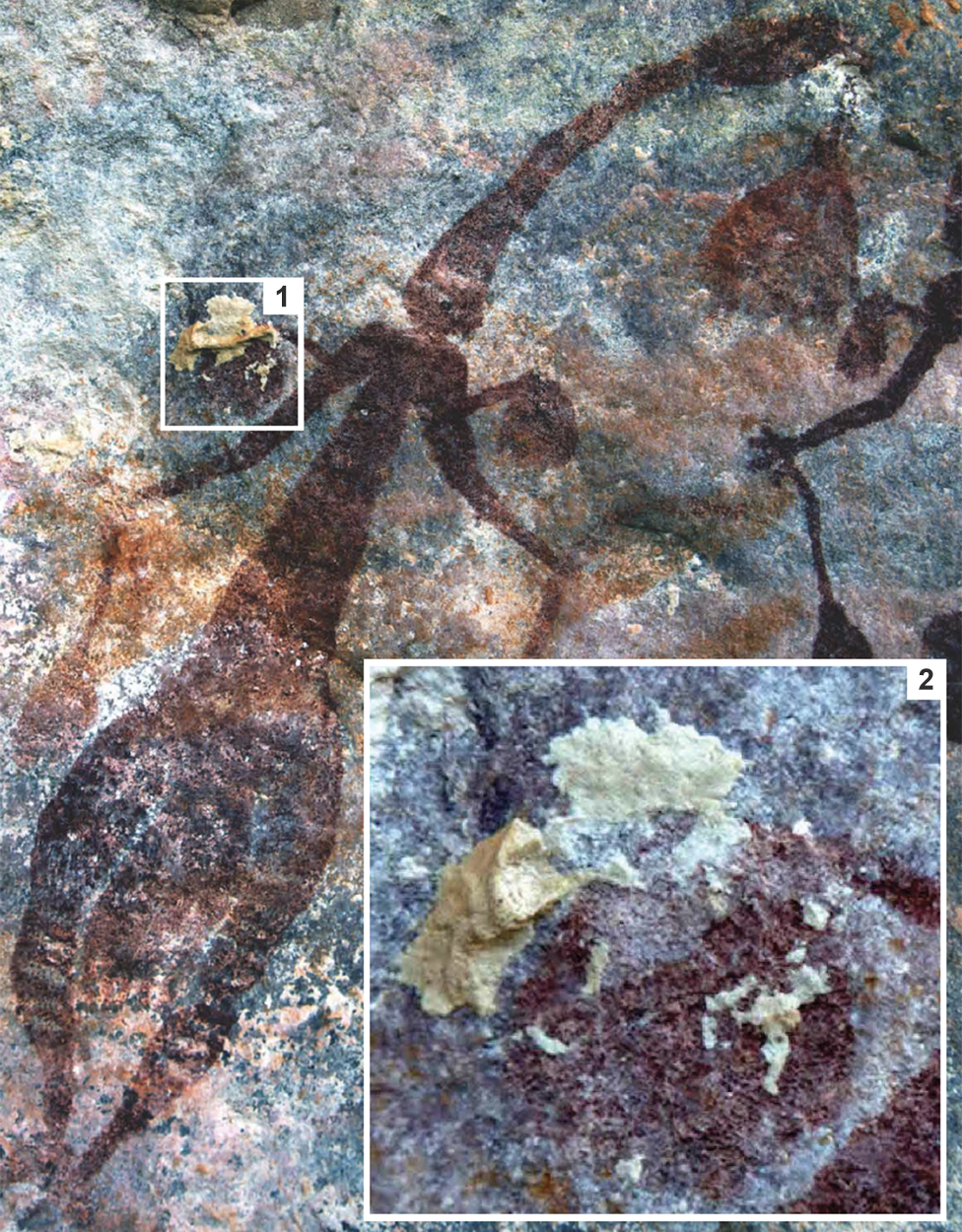

The nests go hard and mineralise over time. (1) Dating nest material on top of the paintings gives a minimum age only. (2) A view of the underlying pigment after the nest's removal

Material that smothers pigment gives a minimum age; underlying material provides a maximum age.

A distribution of dates from many locations enables an estimate to be made for when the Gwion style was in vogue.

"All this is important because we can now begin to match the rock art with other types of information we are getting in the Kimberley, such as the stone tools that are uncovered by archaeologists and what we understand was happening with the climate and sea-levels. Things like that."

The Kimberley likely hosted some of the very first modern humans to reach Australia

The paintings he and his team have been working on are, of course, sites of immense cultural significance.

All the sampling was guided and approved by representatives from the traditional owners of the artwork.

"We couldn't have done what we did without their active support and encouragement," Damien told BBC News.

He's hopeful the mud-wasp dating technique can now be used at more locations right across the north of Australia, and perhaps at other rock art locations in the Americas and Europe.

Gavin Broad is the principal curator in charge of insects at London's Natural History Museum. He described the Australian research as "very smart".

"There was a paper about this some years ago, but the techniques seem to have improved since then," he told BBC News.

"In this study, the nests are made by Sceliphron, which are wasps of the family Sphecidae, superfamily Apoidea.

"These are well-known mud-daubers in much of the warmer parts of the world.

"However, the real diversity of potter wasps is in the Eumeninae, a subfamily of Vespidae (superfamily Vespoidea). Their nests range from holes in mud to simple cells (like Sceliphron) to ornate little pots.

"There are also some spider-hunting wasps (family Pompilidae), which represent at least a third evolution of making clay nests."

Glorious mud: Wasps will build all manner of nest structures using wet soil

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external