Climate change: Pressure on big investors to act on environment

- Published

Investors are facing scrutiny like never before

Ever wondered if your bank or insurance company is funding the coal industry? Or whether your pension fund is backing oil companies drilling new wells in the Arctic?

Investors are facing scrutiny like never before about what they're doing to tackle climate change. And the Bank of England has now launched a push to engage the entire business world.

The aim is to get every company, large or small, to think about global warming as a normal part of their decision-making. And the hope is this will encourage them to come up with plans to become carbon neutral or "net zero".

This comes amid a flurry of climate announcements from some very big corporate names.

The oil giant BP has pledged to be net zero by 2050 and the world's largest asset manager, Blackrock, has warned companies that it won't invest in them unless they try to decarbonise.

There's a series of moves to involve private finance in the run-up to the crucial COP26 climate summit in Glasgow later this year.

Public exposure

The diplomatic focus at that event will be on whether the world's governments commit to deeper cuts in the gases that are heating the planet.

But it's also seen as vital to persuade business to take action in ways that avoid the most dangerous effects of rising temperatures.

One plan is to boost the number of banks, insurers and pension funds signed up to be more open about their carbon footprints and plans to improve them.

Known as the TCFD - or Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures - the project already has the backing of companies with balance sheets worth a total of $135tn.

Under this system, there are no obligations on business leaders to come up with plans to go net zero, but if a company is not taking much action, that fact will be exposed to public gaze.

And already investors with $5tn in assets have committed to making sure their portfolios are carbon neutral by 2050.

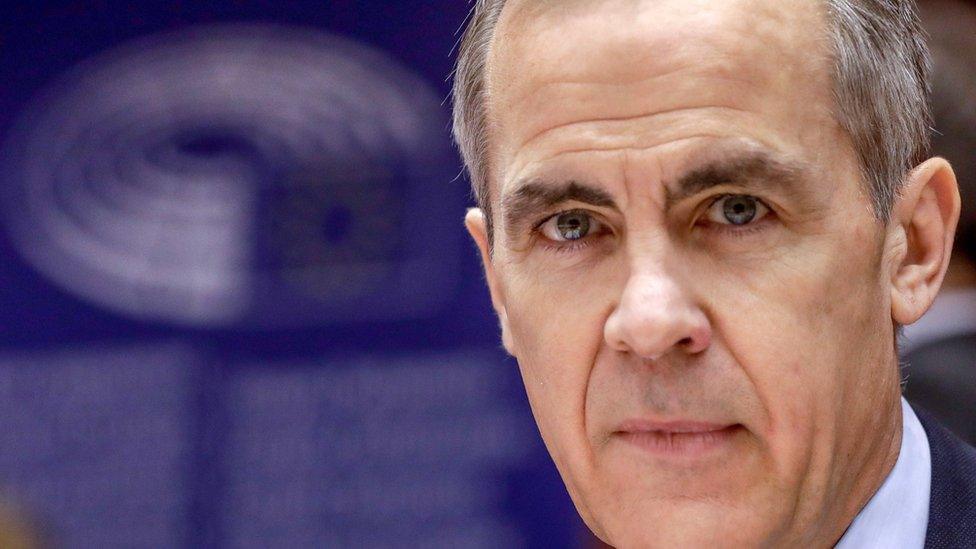

Mark Carney says climate risk management must be "transformed"

Another initiative was launched last year for banks to "stress test" the risks they face of losing money as the world moves away from fossil fuels.

For example, loans to coal-fired power stations could turn bad if a government decides to phase out coal power sooner than expected, leaving the bank with what are called "stranded assets".

Central to this process is Mark Carney, the governor of the Bank of England, who is the prime minister's finance adviser for the climate summit and also a special envoy for the UN secretary-general.

Speaking at an event to launch this agenda, he said: "Given the scale of the climate challenge and the rising expectations of our citizens, 2020 must be a year of climate action where everybody's in, and that includes the world's leading financial centre.

"To identify the largest opportunities and to manage the associated risks, disclosures of climate risk must become comprehensive, climate risk management must be transformed, and investing for a net zero world must go mainstream."

In his first public comments as business secretary and president of the summit, Alok Sharma echoed the appeal for the corporate world to support the move to net zero.

Describing this year as "pivotal for the planet", he told the gathering that dealing with climate change was not just for governments.

"We are calling on action from everyone - businesses, civil society and each part of the global financial system to meet the Paris agreement goals."

- Published12 February 2020