Climate change: Earth's deepest ice canyon vulnerable to melting

- Published

Other space data indicates Denman shed 270 billion tonnes of ice between 1979 and 2017

East Antarctic's Denman Canyon is the deepest land gorge on Earth, reaching 3,500m below sea-level.

It's also filled top to bottom with ice, which US space agency (Nasa) scientists reveal in a new report, external has a significant vulnerability to melting.

Retreating and thinning sections of the glacier suggest it is being eroded by encroaching warm ocean water.

Denman is one to watch for the future. If its ice were hollowed out, it would raise the global sea surface by 1.5m.

"How fast this can happen? Hard to say, since there are many factors coming into play, for example the narrowness of the channel along which Denman is retreating may slow down the retreat," explained Dr Virginia Brancato, from Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and a former scholar at the University of California at Irvine (UCI).

"At present, it is critical to collect more data, and closely and more frequently monitor the future evolution of the glacier," she told BBC News.

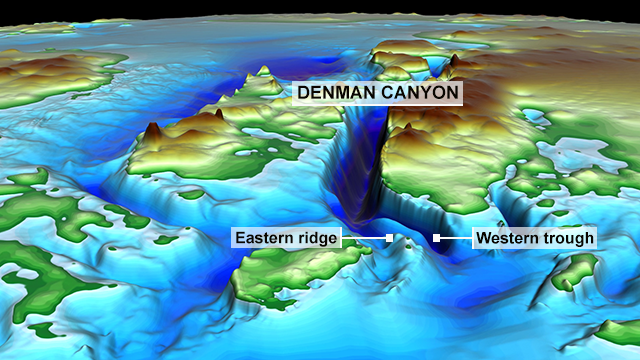

The shape of the bedrock under Denman can explain the asymmetric retreat

Most people recognise the shores around the Dead Sea in the Middle East to have the lowest visible land surface elevation on Earth, at some 430m below sea level. But the base of the gorge occupied by Denman Glacier on the edge of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet (EAIS) actually reaches eight times as deep.

This was only recently established, and it has made Denman a location of renewed scientific interest.

Dr Brancato and colleagues used satellite radar data from 1996 to 2018 to show there's been a marked retreat in the glacier's grounding line. This is the point where the ice stream lifts up and floats as it flows off the land and enters the ocean.

The line has reversed 5-6km in 22 years.

What's interesting about this reversal, however, is that it's asymmetric; it's occurring pretty much all on the western side of the glacier.

The reason, the scientists can now determine, is a buried ridge under the eastern flank which is pinning and protecting that side of the glacier. In contrast, the western flank features a narrow but sizeable trough that would allow warm ocean water to erode the grounding line and push it backwards.

This potentially is an Achilles heel. The further inland the glacier reaches, the deeper its bed - which is a geometry that has been demonstrated to favour more and more melting. If a lot of warm ocean water can find its way to the front of Denman, the opportunity is there to melt out its ice in a significant way.

Denman has an enormous "ice tongue" that floats on the ocean

Most of the ice loss in Antarctica is occurring in the west of the continent. Glaciers in East Antarctica have generally been thought of as stable, as being quiescent. It's only a relatively few ice streams that have been marked out for special attention.

Key among these is Totten Glacier, a colossus that is thinning at a rate of about half a metre a year. But Nasa and UCI researcher Prof Eric Rignot believes Denman is probably the more vulnerable of the two right now. He told BBC News: "I think in terms of the geometry, Denman is more of an Achilles heel than Totten, because it has this deep trough with a retrograde slope that is sort of a perfect crime in the making - as opposed to Totten which has 50km on a prograde slope, of a bed going uphill, before you get into the very deep stuff."

What's lacking currently is better information about the movement of warm water coming from the deep ocean. For the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS), it has been shown there are clear paths for it to get up on to the continental shelf and attack glaciers.

For Denman, this is really a supposition at present - the simplest, best way to explain the observations.

There is some insightful data from instruments mounted on seals that have dived in the area. The marine mammals' information points to routes warm water could take, but the investigations need to be much more extensive.

Dr Emma Smith, recently of the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany, commented: "We need to make more observations beneath the ice shelves and margins of East Antarctica.

"The glaciology community assumed for some time the EAIS was relatively stable compared to WAIS and didn’t worry about it too much. Now that view is slowly shifting as we start to see the vulnerability of certain areas of the EAIS and understand more about the ice-ocean interactions in these areas."

The Nasa-UCI-led team’s assessment of Denman Glacier is published in the American Geophysical Union journal Geophysical Research Letters, external.