Thomas Becket: Alpine ice sheds light on medieval murder

- Published

The murder of Thomas Becket in 1170

Ancient air pollution, trapped in ice, reveals new details about life and death in 12th Century Britain.

In a study, external, scientists have found traces of lead, transported on the winds from British mines that operated in the late 1100s.

Air pollution from lead in this time period was as bad as during the industrial revolution centuries later.

The pollution also sheds light on a notorious murder of the medieval era; the killing of Thomas Becket.

The assassination of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, in 1170 in his cathedral was a gruesome event that made headlines all over Europe.

The King, Henry II, and Becket were once very close - Becket had been Henry's chancellor before he was made Archbishop.

Henry believed the appointment would allow the crown to gain control over the rich, powerful and relatively independent church.

Colle Gnifetti on the Swiss-Italian border is the source of the ice core data

Becket, though, had other plans.

Henry's growing irritation with his Archbishop led the King to reportedly utter the infamous phrase: "Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?"

Unfortunately for Becket, a group of knights loyal to the King decided to make Henry's wish come true.

Becket was beheaded in a brutal attack at Canterbury cathedral on 29 December 1170.

Now scientists have found physical evidence of the impact of the dispute between Henry and Becket in a 72-metre-long ice core, retrieved from the Colle Gnifetti glacier in the Swiss-Italian Alps.

In the same way that trees detail their growth in annual rings, so glaciers compact a record of the chemical composition of the air, trapped in bubbles in the yearly build-up of ice.

Peveril Castle in the Peak District served as the administrative centre of lead mining in the area

Analysing the 800 year-old ice using a highly sensitive laser, the scientists were able to see a huge surge in lead in the air and dust captured in the 12th century.

Atmospheric modelling showed that the element was carried by winds from the north west, across the UK, where lead mining and smelting was booming in the late 1100s.

Lead and silver are often mined together and in this period, mines in the Peak District and in Cumbria were among the most productive in Europe.

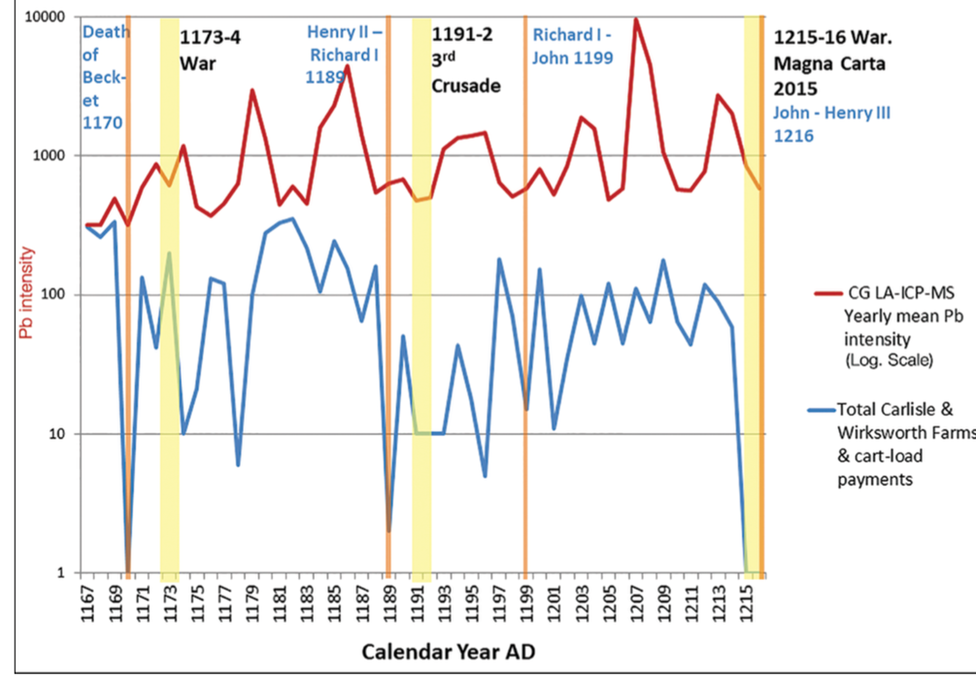

The researchers were able to match the physical records from the ice with the written tax records of lead and silver production in England.

Lead had many uses in this time, from water pipes to church roofs to stained glass windows.

But production of the metal was clearly linked to political events according to the authors of this latest research.

"In the 1169-70 period, there was a major disagreement between Henry II and Thomas Beckett and that clash manifested itself by the church refusing to work with Henry - and you actually see a fall in that production that year," said Prof Christopher Loveluck, from Nottingham University.

A graphic from the study showing the rise and fall of lead production in the late 1100s

Excommunicated by the Pope in the wake of the murder, Henry's attempt at reconciliation is detailed in the ice core.

"To get himself out of jail with the Pope, Henry promised to endow and build a lot of major monastic institutions very, very quickly," said Prof Loveluck.

"And of course, massive amounts of lead were used for roofing of these major monastic complexes.

"Lead production rapidly expanded as Henry tried to atone for his misdemeanours against the Church."

The researchers say their data is also clear enough to show the clear connections between lead production rising and falling during times of war and between the reigns of different kings in this period between 1170 and 1220.

"The ice core shows precisely when one king died and lead production fell and then rose again with the next monarch," said Prof Loveluck.

"We can see the deaths of King Henry II, Richard the Lionheart and King John there in the ancient ice."

The scientists say the scale of mining and smelting of lead in this time period caused the same levels of lead pollution as seen in the 17th century and in 1890.

They argue that the idea that atmospheric pollution started with the industrial revolution are incorrect.

The study has been published, external in the journal Antiquity.

Follow Matt on Twitter., external