Climate secrets of the world's most remote island

- Published

The world's loneliest island can help us better understand the winds blowing around Antarctica

"It's impressive, beautiful and scary as hell to work on."

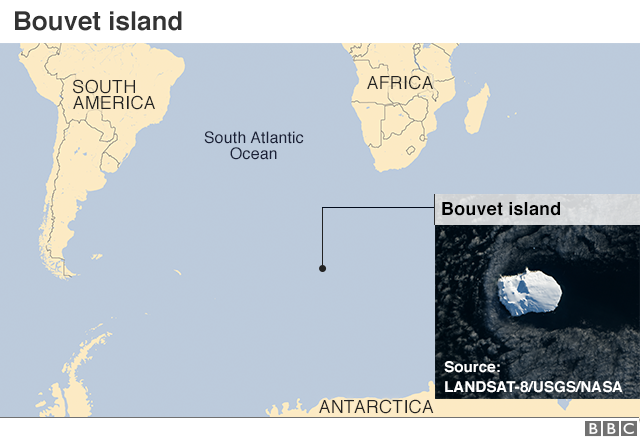

Welcome to Bouvet Island, a small volcanic rock in the South Atlantic.

The Sub-Antarctic territory is thousands of kilometres from civilisation, and its high cliffs and ice-cap mean very few people have ever put a foot on it.

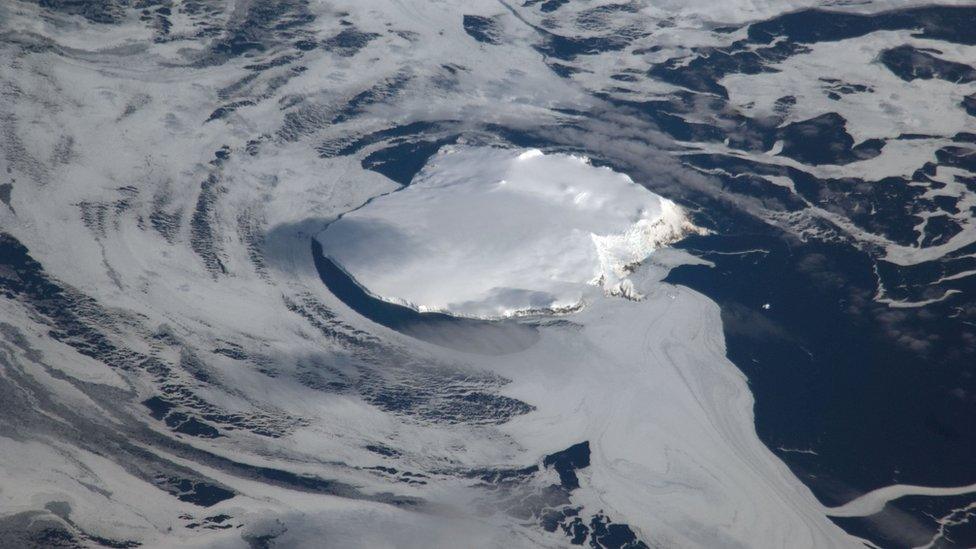

The weather doesn't help. Sticking out of the ocean the way it does means conditions can deteriorate very fast. One minute the skies are clear, the next you're surrounded by cloud.

No wonder sailors call Bouvet the world's most remote island; no wonder writers and science fiction movie-makers keep using it in their storylines.

Other stories from the AGU meeting you might like:

But this loner is drawing increasing scientific interest for what it could tell us about the past climate of Antarctica.

Bouvet is in a unique position by virtue of the fact that it sits out in the belt of westerlies that hurtle around the continent.

And these winds are really important to the way the continent has been changing of late.

They've been driving ocean upwelling, for example; pulling up warm waters from the deep that are then getting under coastal glaciers and melting them. The process is adding to global sea-level rise.

"We know from the recent observational record that these winds have been strengthening but those records only go back 30 or 40 years," says Liz Thomas from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).

"What we're interested in is whether this strengthening is part of natural variability. Do they just do this? Do they speed up and slow down? Or is this something unusual - a human-made impact on the climate."

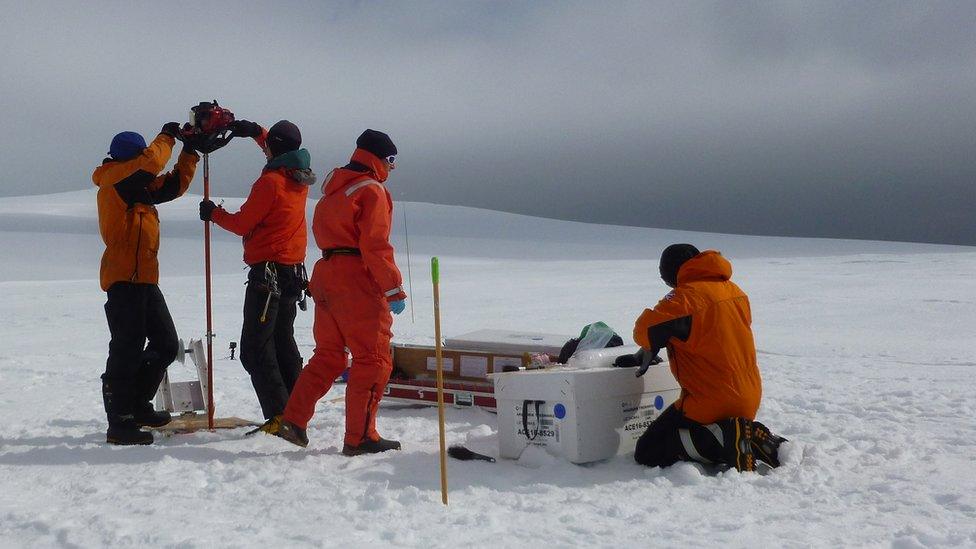

Dr Thomas and colleagues recently dropped on to the island by helicopter - the only way - to drill an ice core. Its compacted snows are like a tape recorder on the past.

The faster and harder the winds blow, the more dust should get incorporated into the core. But there are other markers, too.

Diatoms (tiny algae) that live at the surface of the ocean are whipped up in sea spray. The windier it is, the more concentrated their presence will be in the layers of snow settling on Bouvet.

Liz Thomas: "Bouvet is really the only place we can get this data"

And it's not just a record of winds that Dr Thomas's team can extract.

The group also wants to know how far the annual sea-ice has been extending from Antarctica. In some years, the floes can push out nearly all the way to Bouvet.

PhD student Amy King is examining the core for a suite of particular organic compounds blown on to the island that could serve as a proxy for past sea-ice conditions.

The only way on to the island is by helicopter

These are chemicals associated with the algae, which bloom in the ocean when sea-ice retreats and the water is once again filled with light.

The BAS researcher explains: "The more sea-ice we get in the winter, the greater the extent. When this then melts back in spring, we have more area for phytoplankton growth.

"The more phytoplankton, the more of these fatty acid compounds and methanesulfonic acid we're then going to see in the ice core. So, if we're seeing more ice core compounds from these sources, it means there was more sea-ice in that year."

Amy King: "We had to have luck on our side to get on to Bouvet"

Dr Thomas has been reporting the results from the ice core investigation at the American Geophysical Union, external (AGU) Fall Meeting - the world's largest annual gathering of Earth and space scientists.

The 14m segment of ice the team took off Bouvet only records wind and sea-ice conditions back to 2001. But the scientist is convinced that if the group can return to the island, it will find a drill site with a much deeper history.

She says: "We were only on Bouvet for a matter of hours, because we could only work in a weather window that was good and we had to get off the island quickly when the cloud started to descend. But I definitely think there is the possibility to go back there and drill a very deep core that records several hundreds, if not thousands, of years of climate variability."

The BAS work was undertaken in conjunction with the universities of Maine (US) and Copenhagen (Denmark). It was conducted as part of the Antarctic Circumpolar Expedition led by the Swiss Polar Research Institute.

Bouvet creates its own weather: Cloud develops and disappears very quickly