Coronavirus: A hunt for the 'missing link' host species

- Published

A number of early cases in the pandemic were linked to the Wuhan Seafood Market

It was a matter of "when not if" an animal passed the coronavirus from wild bats to humans, scientists say.

But it remains unclear whether that animal was sold in the now infamous Wuhan wildlife market in China.

The World Health Organization says that all evidence points to the virus's natural origin, but some scientists now say it might never be known how the first person was infected.

Trade in wild animals is under scrutiny as source of this "spillover".

But when wildlife is bought and sold in almost every country in the world, controlling it - let alone banning it - is far from straightforward. Tackling it on a global scale could be the route to stopping a future pandemic before it starts.

The virus originated in bats and was probably passed to humans via an 'intermediate host'

Global health researchers have, for many years, understood how the trade in wild animals provides a source of species-to-species disease transmission. As life-changing as this particular outbreak has been for so much of the global population, it is actually one of many that the trade has been linked to.

As the WHO's technical lead on Covid-19, Dr Maria Van Kerkhove, told the BBC: "We were preparing for something like this as it's not a matter of if, it is a matter of when."

How it began

Infectious disease experts agree that, like most emerging human disease, this virus initially jumped undetected across the species barrier.

Prof Andrew Cunningham, from the Zoological Society of London, explained: "We've actually been expecting something like this to happen for a while.

"These diseases are emerging more frequently in recent years as a result of human encroachment into wild habitat and increased contact and use of wild animals by people."

Officials seize civet cats in Xinyuan wildlife market in Guangzhou to prevent the spread of Sars

The virus that causes Covid-19 joins a murky list of household name viruses - including Ebola, rabies, Sars and Mers - that have originated in wild bat populations.

Some of the now extensive body of evidence about bat viruses, and their ability to infect humans, comes from seeking the source of the 2003 outbreak of Sars, a very closely related coronavirus. It was only in 2017 though that scientists pinned down the "rich gene pool of bat Sars-related coronaviruses" in a single cave in China., external - the possible source of the pandemic.

These viruses have resided in the bodies of bats for millennia, but are pre-programmed with the ability to infect a humans; the key that unlocks some of our cells, where they can replicate.

"In the case of Sars-CoV-2 the key is a virus protein called Spike and the main lock to enter a cell is a receptor called ACE2," explained Prof David Robertson, a virologist from the University of Glasgow. "The coronavirus is not only able to fit that ACE2 lock, "it's actually doing this many times better than Sars-1 [the virus that caused the 2003 outbreak] does", he said.

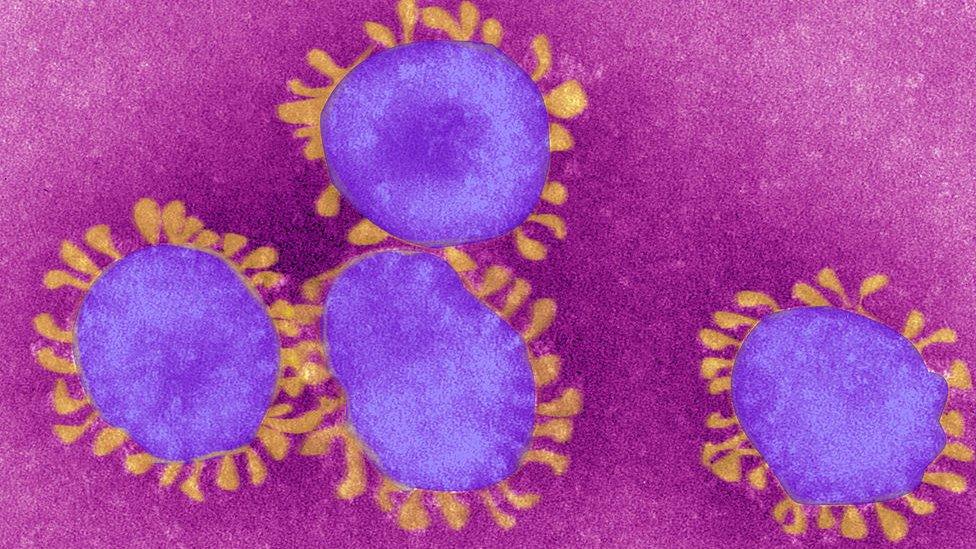

Coronaviruses under the microscope

That perfect fit could explain why the coronavirus is so easily transmitted from person to person; its contagiousness has outpaced our efforts to contain it. But bringing the bat virus to the door of a human cell is where the trade in wildlife plays an important role.

A risky trade

Most of us have heard that this virus "started" in a wildlife market in Wuhan. But the source of the virus - an animal with this pathogen in its body - was not found in the market.

"The initial cluster of infections was associated with the market - that is circumstantial evidence," explained Prof James Wood from the University of Cambridge.

"The infection could have come from somewhere else and just, by chance, clustered around people there. But given that it is an animal virus, the market association is highly suggestive."

Prof Cunningham agreed; wildlife markets, he explained, are hotspots for animal diseases to find new hosts. "Mixing large numbers of species under poor hygienic and welfare conditions, and species that wouldn't normally come close together gives opportunities for pathogens to jump species to species," he explained.

Animals rescued from the exotic pet trade often have to be protected from human disease

Many wildlife viruses in the past have come into humans via a second species - one that is farmed, or hunted and sold on a market.

Prof Woods explained: "The original Sars virus was transmitted into the human population via an epidemic in Palm civets, which were being traded around southern China to be eaten.

"That was very important to know because there was an epidemic in the Palm civets themselves, which had to be controlled to stop an ongoing spillover into humans."

In the search for the missing link in this particular transmission chain, scientists found clues pointing to mink, ferrets and even turtles as a host. Similar viruses were found in the bodies of rare and widely trafficked pangolins, but none of these suspect species has been shown to be involved in this outbreak. What we do know is that our contact with, and trading of, wild animals puts us in the path of new diseases that are silently seeking a host.

Camels can harbour the novel coronavirus, Mers

"Trying to make sure that we are not bringing wildlife into direct contact with ourselves or with other domestic animals is a very important part of this equation," said Prof Wood.

"And there have been various campaigns to ban all trade in animals and all contact with wildlife," he added, "but what you do then is penalise some of the poorest people in the world. In many cases, by introducing measures like that you drive trade underground, which makes it far harder to do anything about."

The WHO has already called for stricter hygiene and safety standards for so-called wet markets in China. But in many cases - such as the trade in bush meat in Sub-Saharan Africa, which was linked with the Ebola outbreak - markets are informal and therefore very difficult to regulate.

"You can't do it from an office in London or in Geneva; you have to do that locally on the ground in every country," added Prof Wood.

Dr Maria Van Kerkhove agreed: "It's very important we work with population and people who are working at the animal/human interface - people who work with wildlife."

What that will be is a truly global and highly complicated effort. But the Covid-19 outbreak appears to have shown us the cost of the alternative.

The BBC's Victoria Gill looks at the wildlife species enjoying lockdown

Follow Victoria on Twitter, external

- Published1 May 2020

- Published25 February 2020