Betelgeuse: Nearby 'supernova' star's dimming explained

- Published

Artwork: Betelgeuse is a red supergiant star, nearly 1,000 times larger than the Sun

Astronomers say big cool patches on a "supergiant" star close to Earth were behind its surprise dimming last year.

Red giant stars like Betelgeuse frequently undergo changes in brightness, but the drop to 40% of its normal value between October 2019 and April 2020 surprised astronomers.

Researchers now say this was caused by gigantic cool areas similar to the sunspots seen on our own parent star.

There had been speculation that Betelgeuse was about to go supernova.

But the star instead began to recover and by May 2020 it was back at its original brightness.

Betelgeuse, which is about 500 light-years from Earth, is reaching the end of its life. But it's not known precisely when it will explode; it could take as long as hundreds of thousands of years or even a million years.

When the giant star does run out of fuel, however, it will first collapse and then rebound in a spectacular explosion. There is no risk to Earth, but Betelgeuse will brighten enormously for a few weeks or months.

It should be visible in daylight and could be as bright as the Moon during night time.

Because it takes about 500 years for the light to reach us, we would be viewing an event that had happened centuries in the past.

Various scenarios have been put forward to explain the recent changes in the brightness of the star.

Astronomers have previously considered that dust produced by the star was obscuring it, causing the steep decline in brightness.

Red giants exhibit a behaviour known as pulsation, caused by changes in the area and temperature of the star's surface layers. Pulsations can eject the outer layers of the star with relative ease.

The released gas cools down and develops into compounds that astronomers call dust.

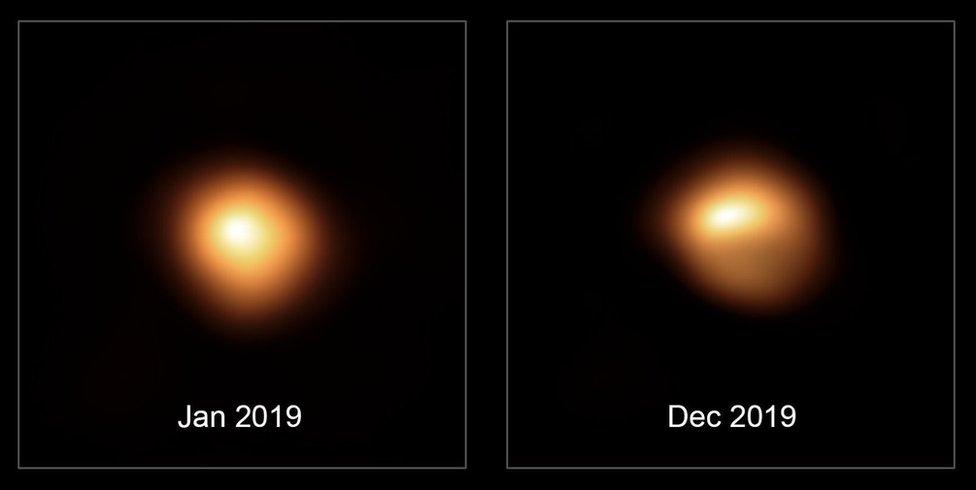

Variations in brightness on the surface of Betelgeuse before and during its darkening. The asymmetries led the authors to conclude that there are huge star spots

To test the dust idea, the astronomers used the Atacama Pathfinder Experiment (APEX) in Chile and the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT) on Mauna Kea in Hawaii. These telescopes measure electromagnetic radiation in the submillimetre wave spectral range. The wavelength of this radiation is a thousand times greater than that of visible light.

This part of the electromagnetic spectrum is particularly good for observing the distribution of cosmic dust.

"What surprised us was that Betelgeuse turned 20% darker even in the submillimetre wave range," said co-author Steve Mairs from the East Asian Observatory in Taiwan, which operates the JCMT.

According to the study, which was led by Thavisha Dharmawardena from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany, the result isn't compatible with the presence of dust.

Instead, the astronomers say, temperature variations in the photosphere - the luminous surface of the star - most likely caused the brightness to drop.

"Corresponding high-resolution images of Betelgeuse from December 2019 show areas of varying brightness. Together with our result, this is a clear indication of huge star spots covering between 50% and 70% of the visible surface and having a lower temperature than the brighter photosphere," said co-author Peter Scicluna from the European Southern Observatory (Eso).

"For comparison, a typical sunspot is the size of the Earth. The Betelgeuse star spot would be a hundred times larger than the Sun. The sudden fading of Betelgeuse does not mean it is going supernova. It is a supergiant star growing a super-sized star spot." said co-author Prof Albert Zijlstra from The University of Manchester, UK.

Compared with our Sun, Betelgeuse is about 20 times more massive and roughly 1,000 times larger. If placed in the centre of the Solar System, it would almost reach the orbit of Jupiter.

The findings are published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters., external

Follow Paul on Twitter., external