Evidence found of epic prehistoric Pacific voyages

- Published

Discussions of contacts between the Americas and Polynesia have often focused on Easter Island

New evidence has been found for epic prehistoric voyages between the Americas and eastern Polynesia.

DNA analysis suggests there was mixing between Native Americans and Polynesians around AD 1200.

The extent of potential contacts between the regions has been a hotly contested area for decades.

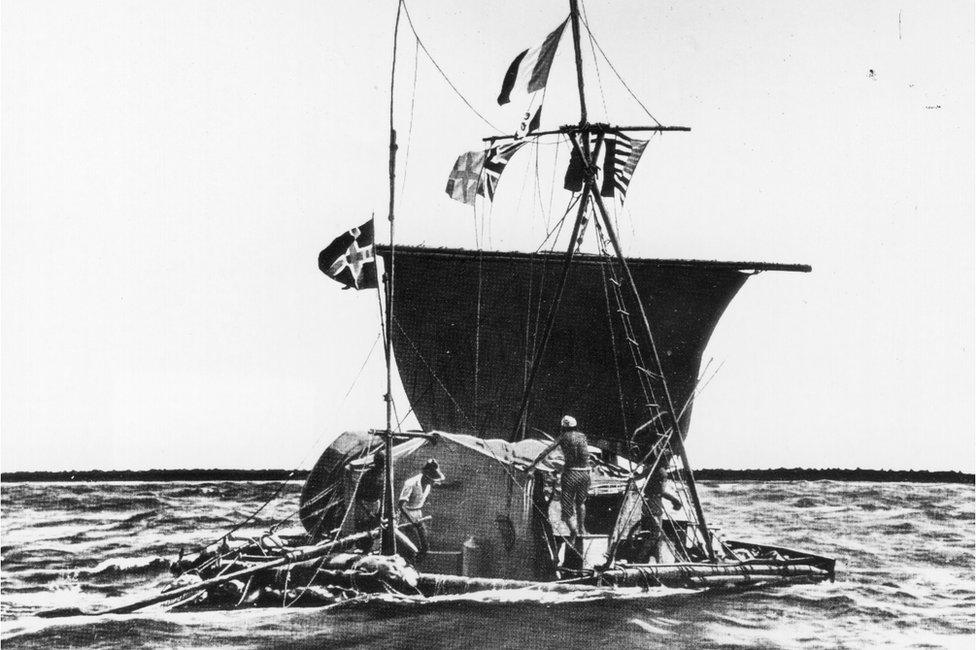

In 1947, Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl made a journey by raft from South America to Polynesia to demonstrate the voyage was possible.

Until now, proponents of Native American and Polynesian interaction reasoned that some common cultural elements, such as a similar word used for a common crop, hinted that the two populations had mingled before Europeans settled in South America.

Opponents pointed to studies with differing conclusions and the fact that the two groups were separated by thousands of kilometres of open ocean.

Alexander Ioannidis from Stanford University in California and his international colleagues analysed genetic data from more than 800 living indigenous inhabitants of coastal South America and French Polynesia.

They were looking for snippets of DNA that are characteristic of each population and for segments that are "identical by descent" - meaning they are inherited from the same ancestor many generations ago.

"We found identical-by-descent segments of Native American ancestry across several Polynesian islands," said Mr Ioannidis.

"It was conclusive evidence that there was a single shared contact event."

Thor Heyerdahl made a Pacific journey on a balsa raft to show the voyage was possible

In other words, Polynesians and Native Americans met at one point in history, and during that time children with both Native American and Polynesian ancestry were born.

Statistical analyses confirmed the event occurred around AD 1200, at about the time Pacific islands were originally being settled by Polynesians.

Asked who he thought made contact first, Mr Ioannidis ventured that it may have been Polynesian navigators reaching South America.

"Because the timing is exactly at the time that the Polynesians were embarking on their longest voyages of discovery and soon after they discovered Easter Island, which is extremely remote, and also later settling New Zealand and Hawaii, they had no idea there was going to be a continent eventually and they were going to run out of islands, so I think they probably did find a continent," he said.

"They would sail upwind when they were trying to discover new islands, the anthropologists I believe say this, because if they didn't find an island they could return home - that way, they could return home swiftly. They were sailing across 1,000km of open ocean here."

The team were also able to localise the source of the Native American DNA to indigenous groups in modern-day Colombia.

Previous studies of the genomes (the full complement of DNA in the nuclei of human cells) of people from these regions have focused around contact on Easter Island - famous for its giant stone faces - because it is the closest inhabited Polynesian island to South America.

However, the study in Nature journal, external supports the idea that first contact occurred on one of the archipelagos of eastern Polynesia - as proposed by Heyerdahl.

Wind and current simulations have shown that drift voyages departing from Ecuador and Colombia are the most likely to reach Polynesia, and that they arrive with the highest probability in the South Marquesas islands, followed by the Tuamotu Archipelago.

Both of these archipelagos lie at the heart of the region of islands where the researchers found an ancestral genetic component from Colombian Native Americans.

Previously, researchers had noted superficial similarities between monolithic statues in Polynesia and others found in South America.

But other evidence comes from a correspondence between the word for sweet potato (a crop that originated in South America), which is "kumala" in Polynesia and "cumal" in, for example, the language used by the Cañari people of Ecuador.

Heyerdahl embarked on his "Kon-Tiki" raft expedition from Callao, Peru, on 28 April 1947 with five companions. They sailed on the raft for 101 days, traversing 6,900km (4,300 miles) of ocean before smashing into a reef at Raroia in the Tuamotus on 7 August 1947.