Climate change: Satellites find new colonies of Emperor penguins

- Published

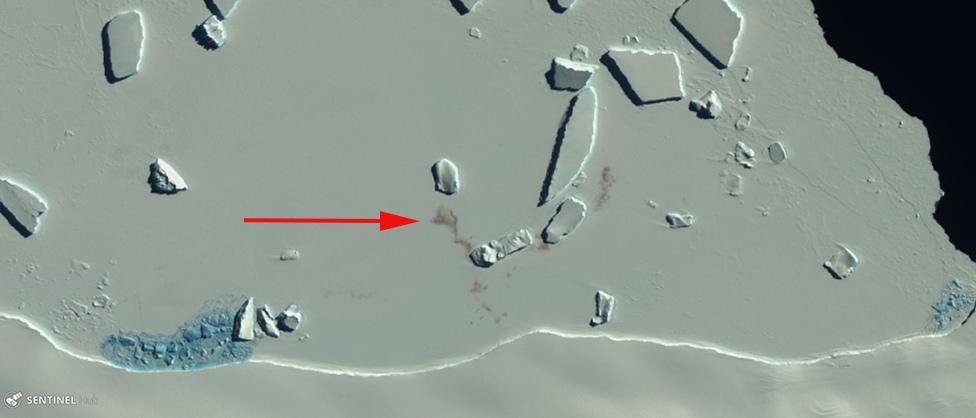

Guano stains: A new colony on fast ice that has formed around grounded icebergs

Satellite observations have found a raft of new Emperor penguin breeding sites in the Antarctic.

The locations were identified from the way the birds' poo, or guano, had stained large patches of sea-ice.

The discovery lifts the global Emperor population by 5-10%, to perhaps as many as 278,500 breeding pairs.

It's a welcome development given that this iconic species is likely to come under severe pressure this century as the White Continent warms.

The Emperors' whole life cycle is centred around the availability of sea-ice, and if this is diminished in the decades ahead - as the climate models project - then the animals' numbers will be hit hard.

One forecast suggested the global population could crash by a half or more under certain conditions come 2100.

Artwork: Sentinel-2 satellites frequently image Antarctica's margin where the Emperors live

The British Antarctic Survey (BAS) used the EU's Sentinel-2 spacecraft to scour the edge of the continent for previously unrecognised Emperor activity.

The satellites' infrared imagery threw up eight such breeding sites and confirmed the existence of three others that had been mooted in the era before high-resolution space pictures.

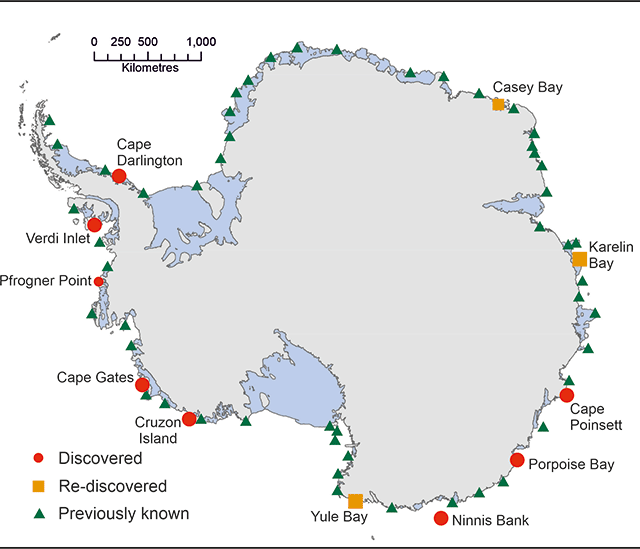

The new identifications take the number of known active breeding sites from 50 to 61. Two of the new locations are in the Antarctic Peninsula region, three are in the West of the continent and six in the East.

They are all in gaps between existing colonies. Emperor groups, it seems, like to keep at least 100km between themselves. The new sites maintain this distancing discipline.

Emperor penguins need a reliable and stable platform of sea-ice

It's impossible to count individual penguins from orbit but the BAS researchers can estimate numbers in colonies from the size of the birds' huddles.

"It's good news because there are now more penguins than we thought," said BAS remote-sensing specialist Dr Peter Fretwell.

"But this story comes with a strong caveat because the newly discovered sites are not in what we call the refugia - areas with stable sea-ice, such as in the Weddell Sea and the Ross Sea. They are all in more northerly, vulnerable locations that will likely lose their sea-ice," he told BBC News.

Breeding success for Emperors rests upon the presence of so-called "fast ice". This is the sea-ice that sticks to the edge of the continent or to icebergs.

It's low and flat, and an ideal surface on which to lay an egg, incubate it and then raise the subsequent chick in its first year of life.

But this seasonal ice needs to be long-lived, to stay intact for at least eight or nine months to be useful.

If it forms too late or breaks up too early, the young birds will be forced into the sea before they're ready, before they've lost their down and grown water-proof feathers.

Likewise for the adults. They undergo a dramatic moult in the summer months of January and February. They too risk drowning if the fast ice melts away and they don't have the right plumage to resume swimming.

Antarctic sea-ice trends in recent decades have been pretty stable, albeit with some big regional shifts. But the climate models foresee significant losses this century.

Even under the Paris Agreement's best-case scenario with a global temperature increase of no more than 1.5C above pre-industrial times, the population is likely to decrease by at least a third over the next three generations, the experts say.

The largest of the new colonies is at Cape Gates with several thousand breeding pairs

It's this troubling outlook that led researchers last year to call for the conservation status of Emperors to be upgraded.

At the moment, they are classified as "Near Threatened" by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the organisation that keeps the lists of Earth's endangered animals.

A proposal has now been submitted to put Emperors into the more urgent "Vulnerable" category.

Details of the Sentinel search for Emperors is reported in the journal Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation, external.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published7 July 2020

- Published9 October 2019

- Published25 April 2019