Beirut blast was 'historically' powerful

- Published

The blast that devastated large parts of Beirut in August was one of the biggest non-nuclear explosions in history, experts say.

The Sheffield University, UK, team says a best estimate for the yield is 500 tons of TNT equivalent, with a reasonable upper limit of 1.1 kilotons.

This puts it at around one-twentieth of the size of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, in 1945.

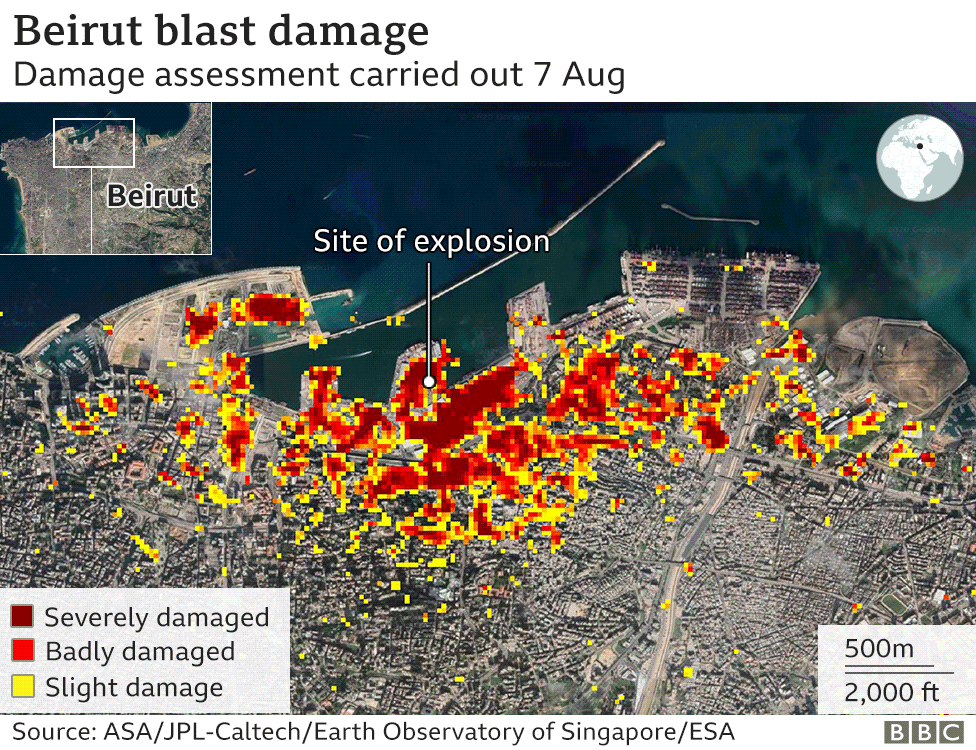

The team mapped how the shock wave propagated through the city.

The group hopes its work can help emergency planners prepare for future disasters.

"When we know what the yield is from these sorts of events, we can then work out the loading that comes from that. And that tells us how to construct buildings that are more resilient," said Dr Sam Rigby from Sheffield's Blast and Impact Engineering Research Group.

"Even things like glazing. In Beirut, glazing damage was reported up 10km away from the centre of the explosion, and we know falling glass causes a lot of injuries."

The 4 August explosion was the result of the accidental detonation of approximately 2,750 tonnes of improperly stored ammonium nitrate. The blast led to some 190 deaths, as well as more than 6,000 injuries.

Starting with the epicentre, we follow how the 4 August blast ripped through the city, bringing life to a halt

The Sheffield team arrived at its estimate by studying videos of the event posted on social media.

When the group did this in the immediate aftermath of the blast, it produced an initial estimate in the range of 1.0-1.5 kilotons of TNT.

But this was based on only a limited set of videos, which the team discovered may have dropped frames either when being uploaded to social media or when being pulled down.

The group has now had the chance to review many more videos from the event (16 in total) to generate a broader set of data points from which to make the calculations. This has resulted in the yield estimate being revised downwards slightly.

"Think of it like a kid on a swing," said Dr Rigby. "If you push the child and see how far they go, you can then work out how hard the push was. That's essentially how we work out the yield."

In a matter of milliseconds, the explosion released the equivalent of around 1GWh of energy. This is enough to power more than 100 homes for a year, say the researchers.

The nuclear device dropped on Hiroshima was in the range of 13-15 kilotons of TNT equivalent. By way of comparison, one of the US military's biggest conventional weapons, the GBU-43/B MOAB ("Massive Ordnance Air Blast") device, has a yield of around 11 tons.

"The Beirut explosion is interesting because it sits almost directly in a sort of no-man's land between the largest conventional weapons and nuclear weapons," said Dr Rigby

"It was about 10 times bigger than the biggest conventional weapon, and 10 to 20 times smaller than the early nuclear weapons," he told BBC News.

Dr Rigby said Beirut was in the top 10 in terms of the most powerful accidental non-nuclear explosions in history (neglecting much more energetic natural occurrences like volcanoes, asteroid impacts, etc); and probably just outside the top 10 when some nuclear mock-up tests (such as "Minor Scale" - the largest ever man-made non-nuclear explosion, which was around 3.2 kilotons of TNT) are included.

Beirut was about a third of Minor Scale.

The largest accidental non-nuclear explosion in history occurred in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1917, when two ships (one carrying explosives) collided. That was nearly 3 kilotons of TNT equivalent, so again Beirut was around a third this size, give or take. More recently, the 2015 explosion in Tianjin (China) was only around half the yield of Beirut. This again involved ammonium nitrate.

"Beirut's certainly the most powerful non-nuclear explosion of the 21st Century," said Dr Rigby.

The new analysis is published in the journal Shock Waves., external

Other scientists have also estimated the yield of the Beirut explosion.

The BGR group in Germany used seismic, infrasonic, and hydroacoustic data from the event; and Dr Jorge Díaz studied the physics of the evolution of the explosion fireball using Twitter videos.

"Remarkably, we all used publicly available data and found consistent results by implementing completely different methods," said Dr Díaz, who is affiliated to Indiana University, Bloomington, US.

An ammonium nitrate explosion can release toxic gases