A68 iceberg on collision path with South Georgia

- Published

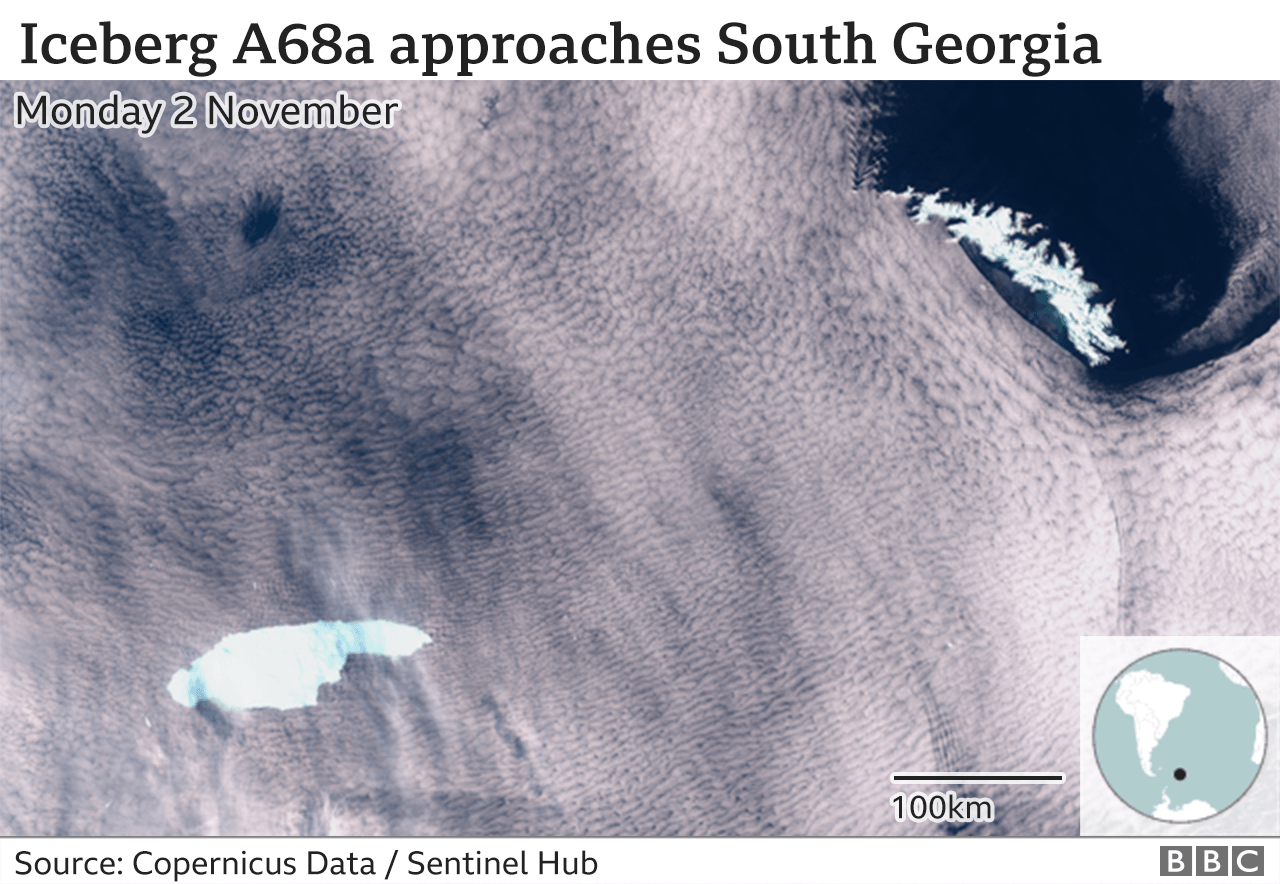

Pointing the way: Viewed from space, A68a has the look of a hand with an outstretched index finger

The world's biggest iceberg, known as A68a, is bearing down on the British Overseas Territory of South Georgia.

The Antarctic ice giant is a similar size to the South Atlantic island, external, and there's a strong possibility the berg could now ground and anchor itself offshore of the wildlife haven.

If that happens, it poses a grave threat to local penguins and seals.

The animals' normal foraging routes could be blocked, preventing them from feeding their young properly.

And it goes without saying that all creatures living on the seafloor would be crushed where A68a touched down - a disturbance that would take a very long time to reverse.

"Ecosystems can and will bounce back of course, but there's a danger here that if this iceberg gets stuck, it could be there for 10 years," said Prof Geraint Tarling from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), external.

"And that would make a very big difference, not just to the ecosystem of South Georgia but its economy, external as well," he told BBC News.

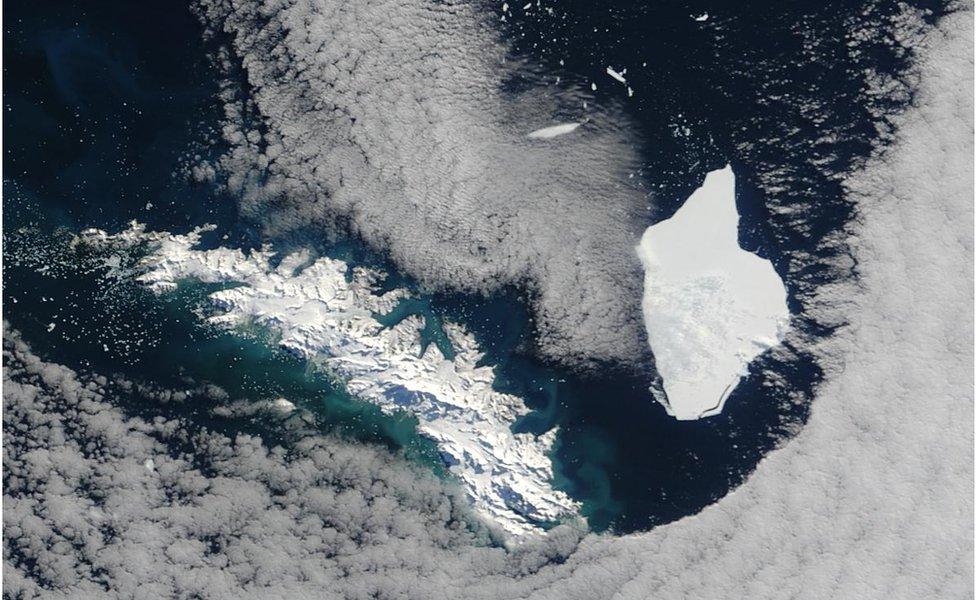

South Georgia is famous for its abundant wildlife

The British Overseas Territory is something of a graveyard for Antarctica's greatest icebergs.

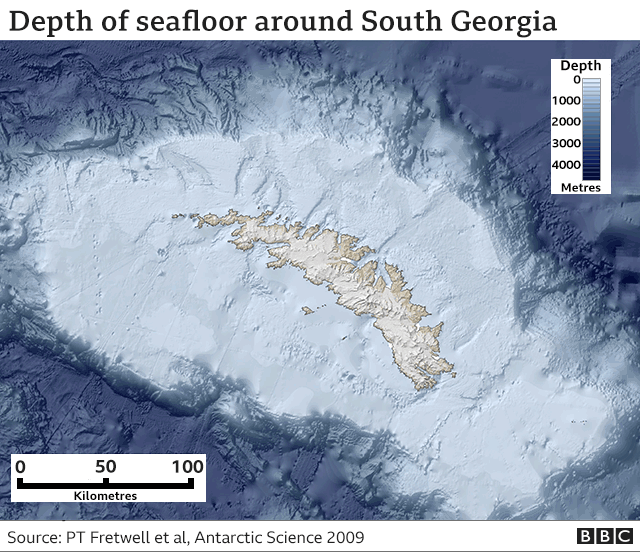

These tabular behemoths get drawn up from the White Continent on strong currents, only for their keels to then catch in the shallows of the continental shelf that surrounds the remote island.

Time and time again, it happens. Huge ice sculptures slowly withering in sight of the land.

A68a - which has the look of a hand with a pointing finger - has been riding this "iceberg alley" since breaking free from Antarctica in mid-2017. It's now just a few hundred km to the southwest of the BOT.

The graveyard of giants: Icebergs routinely anchor offshore

Roughly the size of the English county of Somerset (4,200 sq km), the berg weighs hundreds of billions of tonnes. But its relative thinness (a submerged depth of perhaps 200m or less) means it has the potential to drift right up to South Georgia's coast before anchoring.

"A close-in iceberg has massive implications for where land-based predators might be able to forage," explained Prof Tarling.

"When you're talking about penguins and seals during the period that's really crucial to them - during pup- and chick-rearing - the actual distance they have to travel to find food (fish and krill) really matters. If they have to do a big detour, it means they're not going to get back to their young in time to prevent them starving to death in the interim."

When the colossus A38 grounded at South Georgia in 2004, countless dead penguin chicks and seal pups were found on local beaches.

With a draft of about 200m, A68a has the potential to catch on the shallow shelf around the island

The BAS researcher is in the process of trying to organise the resources to study A68a at South Georgia, should it do its worst and ground in one of the key productive areas for wildlife and the local fishing industry.

The potential impacts are multi-faceted - and not all negative, he stresses.

For example, icebergs bring with them enormous quantities of dust that will fertilise the ocean plankton around them, and this benefit will then cascade up the food chain.

Although satellite imagery suggests A68a is on a direct path for South Georgia, it might yet escape capture. Anything is possible, says BAS remote-sensing and mapping specialist Dr Peter Fretwell.

"The currents should take it on what looks like a strange loop around the south end of South Georgia, before then spinning it along the edge of the continental shelf and back off to the northwest. But it's very difficult to say precisely what will happen," he told BBC News.

Colleague Dr Andrew Fleming said a request was going into the European Space Agency for more satellite imagery, particularly from its pair of Sentinel-1 radar spacecraft, external.

These imagers work at wavelengths that allow them to see through cloud, meaning they can track the iceberg no matter what the weather conditions are like.

"A68a is spectacular," Dr Fleming said. "The idea that it is still in one large piece is actually remarkable, particularly given the huge fractures you see running through it in the radar imagery. I'd fully expected it to have broken apart by now.

"If it spins around South Georgia and heads on northwards, it should start breaking up. It will very quickly get into warmer waters, and wave action especially will start killing it off."

When A38 turned up in 2004, it caused immense difficulties for foraging seals and penguins

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external