Europe moves ahead with Ariel exoplanet mission

- Published

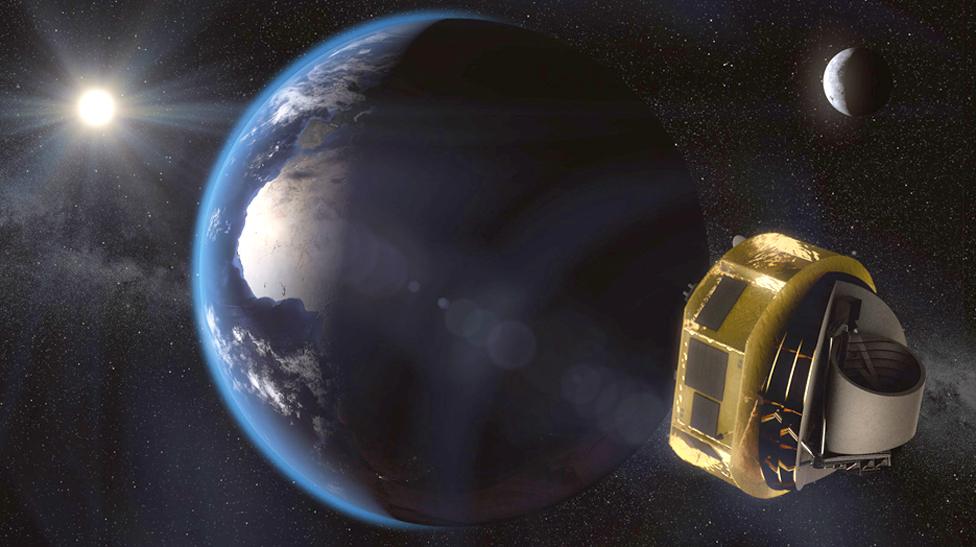

Artwork: The Ariel space telescope will be about a tonne and a half at launch

The Ariel space telescope, which will study the atmospheres of distant worlds, has the green light to proceed.

European Space Agency (Esa) member states formally adopted the project on Thursday, signing off two years of feasibility studies.

The near-billion-euro observatory is now clear to launch in 2029.

Ariel will probe the gases that shroud exoplanets to try to understand how these objects formed and how they have evolved through time.

The findings are expected to help put the nature of our own Solar System in some wider context.

While it is undoubtedly a grand endeavour for the whole of European space research, Ariel is of particular importance to the UK.

Scientifically, the mission will be led from University College London by principal investigator Prof Giovanna Tinetti. But on the technical front, too, Britain will play a major role.

The "business end" of the observatory - its mirror system and instrumentation - will be assembled and tested at RAL Space on the Harwell Campus in Oxfordshire.

"We're very good at exoplanet research in the UK; we've got one of the largest science communities in the world. So, yes, we want to have a big part in Ariel," said Dr Caroline Harper, the head of science at the UK Space Agency.

"And, of course, in RAL Space we have world-class system engineering, with the expertise and facilities in one place to do the assembly, integration and testing," she told BBC News.

Atmospheric Remote-Sensing Infrared Exoplanet Large-survey

Artwork: The mission will cost in excess of half a billion euros

Launch year: 2029

Mission lifetime: 4 years

Payload mass: 500kg

Launch mass: 1,500kg

Ariel will be despatched to a special observing position that is about 1.5 million km from Earth

The Atmospheric Remote-Sensing Infrared Exoplanet Large-survey (Ariel) telescope was selected as Esa's fourth "Medium Class" mission in its Cosmic Vision series of projects back in 2018.

As is customary, however, member states demanded a period of assessment following this choice to ensure the necessary finances and technology were available to carry the venture through to completion.

Thursday's decision signals that no showstoppers have been identified.

The Ariel consortium will now move forward with the build phase, which will involve the fabrication of various test artefacts, leading eventually to the production of all the flight hardware.

One of the big challenges will be in making an all-aluminium telescope system. This includes the 1.1m by 0.7m primary mirror, which is to be coated in silver.

It's challenging because this system will have to work in space at very low temperatures, at below minus 230C.

"It's the first time they've built quite such a large telescope out of aluminium," said Dr Rachel Drummond, the Ariel national project manager at RAL Space.

"The reason you choose mainly one metal is so it all shrinks together, as it goes cold, so the whole thing stays in focus, even when it's getting smaller.

"When we come to put it into a thermal-vacuum (test) chamber and cool it down to about 40 kelvins, we'll want to see that we don't get any sort of deformation, that things don't bend or move such that the light we're observing isn't actually going into the instrumentation."

Ariel plans to observe up to a 1,000 exoplanets during its main mission phase.

It will do this by watching these worlds as they move in front and behind their host stars. Information about the chemistry of the planets' atmospheres will be imprinted in the starlight coming towards us, and Ariel will extract this detail using its spectroscopic technologies.

RAL Space has a deadline of late 2026 to deliver the science payload.

This will be incorporated into a spacecraft chassis, which will be built either by Thales Alenia Space France or Airbus France. The two aerospace companies are currently in competition and a down-selection to one prime contractor is likely to occur in about a year's time.

Giovanna Tinetti: "What is the 'standard model' of planets?"

Ariel is one of three Esa exoplanet missions. Already launched, last year, is the Swiss-led Cheops telescope, which is refining the size measurement of known worlds (important if you want to say something about the properties of those bodies).

Then comes the Plato space telescope, which is also expected to launch in the second half of the 2020s. Plato's goal is to detect and characterise true Earth-like rocky planets.

The Ariel team says it will have an open science policy whereby data will be made available immediately to the wider science community. It's hoped this will accelerate the insights that emerge from the mission.

"Ariel will enable planetary science far beyond the boundaries of our own Solar System,” said Prof Günther Hasinger, Esa’s director of science. "The adoption of Ariel cements Esa’s commitment to exoplanet research and will ensure European astronomers are at the forefront of this revolutionary field for the next decade and well beyond."