Nasa's new 'megarocket' set for critical tests

- Published

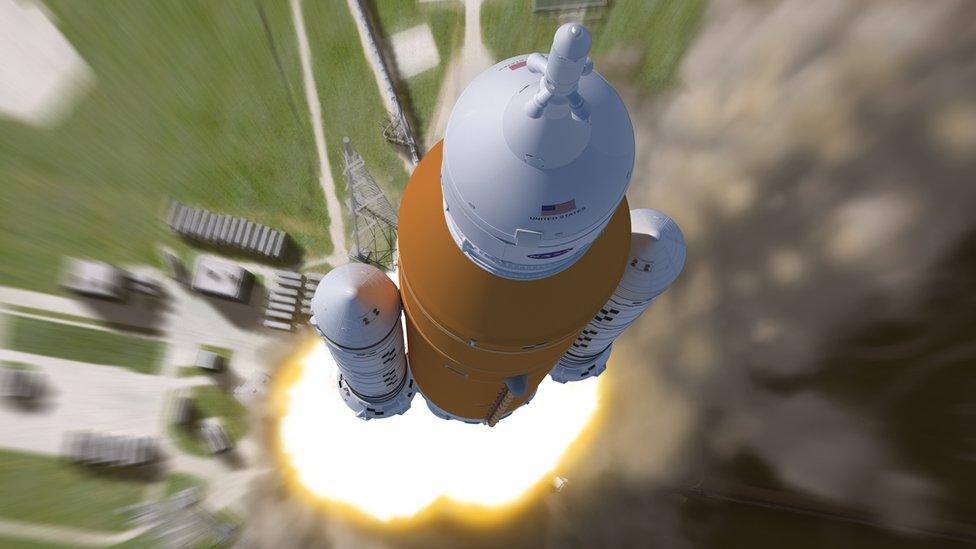

The orange SLS core stage is being tested on the B-2 test stand at Stennis Space Center

Nasa has been developing a "megarocket" to send humans to the Moon and, eventually, Mars. The last critical tests of the giant launcher's core section are expected to take place within the next few weeks. Sometimes compared to the iconic Saturn V, can the Space Launch System (SLS) help capture the excitement of lunar exploration for a new generation?

In southern Mississippi, near the border with Louisiana, engineers have been putting a remarkable piece of hardware through its paces.

A giant orange cylinder is suspended on an equally imposing steel structure called the B-2 test stand on the grounds of Stennis Space Center, a Nasa test facility outside the city of Bay St Louis.

Measuring about 65m (212ft) from top to bottom, the cylinder represents the core of a space vehicle more powerful than anything the world has seen since the 1960s.

It's called the Space Launch System (SLS) and it consists of the liquid-fuelled core stage - with four powerful RS-25 engines at its base - and two solid fuel boosters which are strapped to the sides.

The fully assembled vehicle provides the massive thrust force necessary to blast astronauts off the Earth and hurl them towards the Moon. Under Nasa's Artemis programme, the next man and the first woman will be despatched to the lunar surface in 2024. It will be the first crewed landing on Earth's only natural satellite since Apollo 17 in 1972.

It may use technology developed for the space shuttle, but in many ways, the SLS is a modern heir to the Saturn V, the gigantic rocket that lofted the Apollo lunar missions.

After a decade of development, the SLS is now approaching a critical stage. A year-long programme of testing for the core stage is coming to an end. Called the Green Run, it's designed to iron out any issues before the rocket's maiden flight, scheduled for November 2021.

On 12 January this year, the first SLS core stage was shipped to Stennis on a barge from the New Orleans factory where it was assembled. It was then lifted by cranes and installed in a vertical position on the B-2 test stand.

Ryan McKibben, SLS Green Run test conductor at Stennis Space Center, told BBC News: "When you actually see the real deal, with the real avionics, the real tanks - the liquid hydrogen tank which holds 500,000 gallons and the liquid oxygen tank with over 200,000 gallons - it is an incredible vehicle."

In New Orleans, the core stage is guided towards a barge for transport to Stennis Space Center in January this year

The Green Run is split into eight parts - or test cases. Since the beginning of the year, engineers from Nasa and Boeing, the rocket's prime contractor, have been working through these individual tests. They have included powering up the avionics (flight electronics), evaluating the performance of different systems and components, and simulating problems.

"We're very fortunate to be able to put it through its paces: power it up, do leak checks, even pressurise some systems," says Ryan McKibben.

"One of the test cases, test case five, we ended up gimballing the engines - that's when we move them around hydraulically so that you can do course corrections during flight. It's been a lot of fun."

During its first mission next year, known as Artemis-1, the SLS will launch an uncrewed Orion capsule on a loop around the Moon. It will allow Nasa to evaluate the capsule before astronauts are allowed on.

The first SLS core is installed on the test stand in Mississippi

The remaining two core stage tests are crucial. Number seven, known as the wet dress rehearsal (WDR) involves a full loading of the core stage tanks with liquid hydrogen (LH2) - the rocket's fuel - and liquid oxygen (LOX), which makes the fuel burn. Together, these are known as propellants.

A waterway snakes through the grounds of Stennis Space Center, linking it to the nearby Pearl River. This allows heavy equipment and hardware to be shipped between different Nasa sites. A total of six barges carrying LH2 and LOX will be docked near the B-2 test stand during the wet dress rehearsal.

The cold (cryogenic) propellants will be piped from these barges to the core stage tanks. This is relatively easy with hydrogen - a very light fluid, but oxygen is heavy, and has to be pumped.

The loading will take place over about six-and-a-half hours. After the tanks are full, they will be continually topped up, because the propellants are at temperatures of several hundreds of degrees below zero and some of it boils off over time. The liquids also flow through the turbopumps - which feed propellant to the engine combustion chambers - and the engines themselves. This helps prepare the systems to be started.

Engineers will gather data and compare it against mathematical models to check that the entire system behaves as expected.

The Stennis teams will simulate a launch countdown during the WDR, taking things up to the T-minus (time remaining) 33 seconds mark.

Workers inside the huge SLS hydrogen tank use a technique called friction stir welding to plug holes

"We'll spend about two weeks looking at the data to make sure all the systems behaved as expected," John Shannon, vice president and SLS programme manager at Boeing, told journalists last month.

"We'll go out and inspect the vehicle, make sure there are no surprises."

The eighth and final test, called the engine "hotfire", will pick up from the 33-second mark. With the core stage anchored to the stand, the hotfire will see its four powerful RS-25 engines fired together for the first time.

"It's a full duration burn - that's what we're targeting," said Mr McKibben. "It's exciting to light more than one off at the same time... We haven't done that for close to 40 years at the site."

Aside from the engineering data it will generate, the test will demonstrate the awesome power of the SLS.

The engines - the same ones that powered the now-retired space shuttle orbiter - will generate a whopping 1.6 million pounds of thrust. That's roughly the same as six 747 airliners at full power.

Although the propellants are at hundred of degrees below freezing when they're fed to the RS-25 engines, the exhaust that emerges is 3,315C (6,000F) - hot enough to boil iron.

How water is used to cool rocket exhaust

"We fire down into a bucket that has a lot of water going into it. The water keeps it from burning straight through the test stand," said Ryan McKibben.

Hundreds of thousands of gallons of water are directed into the flame bucket to cool the exhaust. In addition, tens of thousands of gallons will be used to create a water "curtain" around the engines to suppress the noise generated when they fire for 8.5 minutes.

This is done to protect the core stage from vibrations while it is anchored to the stand.

"We are definitely excited, because you don't get to try out a new space vehicle very often," says McKibben.

Engineers have recently been troubleshooting an issue with a pre-valve, which supplies liquid hydrogen fuel to the RS-25 engines. But Mr McKibben says this is "something we're more than capable of handling".

The testing has largely proceeded smoothly, but there was a five-week stop due to Covid-19. In addition, work at the site also had to be shut down six times due to tropical weather, given the particularly active hurricane season.

Artwork: How the SLS will look when it launches

Originally scheduled to take place in early to mid-November, the wet dress rehearsal and hotfire are now expected to take place within the next six to three weeks.

Teams are conscious of meeting a January timeline for delivering the core stage to Kennedy Space Center in Florida, where it will undergo final processing and preparations for launch in November 2021.

McKibben says he believes teams can still meet this schedule, but adds that it depends on how the core performs during WDR.

The SLS has long been a lightning rod for those who would prefer Nasa to hand over more of its activities to commercial companies, and those who believe the government rocket, designed specifically to carry humans and based on proven technology, is the best option for deep space exploration.

The SLS will have cost more than $17bn by the end of this year, but without significant modifications, no existing commercial rocket can send Orion, astronauts and heavy cargo to the Moon in one go.

The Saturn V launches Apollo 11 in 1969. The SLS is the most powerful rocket built since the Saturn

There is no clear sign as yet of the direction in which a Joe Biden administration might take the human spaceflight programme.

The Artemis effort enjoys bipartisan support. But some Capitol Hill lawmakers may not necessarily be as wedded to the timeline, announced last year by Mike Pence, of landing humans on the Moon by 2024.

There's no doubt that the Moon programme has recaptured some of the excitement of the Apollo era. Mr McKibben says he is in awe of what the Saturn V engineers did back in the 1960s. It's not lost on him that the B-2 test stand was built to test the five engines of the Saturn's first stage.

Going mobile with his laptop, Mr McKibben shows me a car he owns: a navy Dodge Dart from 1969 - the year Neil and Buzz touched down in the Sea of Tranquility.

"It's something an old test guy that would have been testing the Saturn V would have driven," he tells me.

"I'm kind of a nostalgic person."

Follow Paul on Twitter., external