A68a: World's biggest iceberg is fraying at the edges

- Published

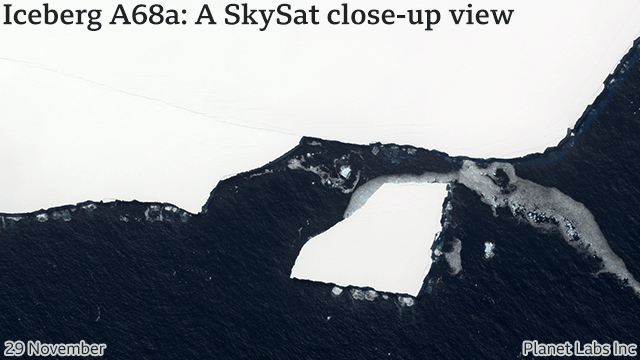

This is the first high-resolution image of the berg's condition in months

Iceberg A68a has been imaged at high resolution for the first time in months - and it's in a ragged condition.

The world's biggest berg is riven with cracks. Battered by waves and under constant attack from warm waters, it's now shedding countless small blocks.

A68a, which broke away from Antarctica in 2017, is on a direct heading for the South Atlantic island of South Georgia, external.

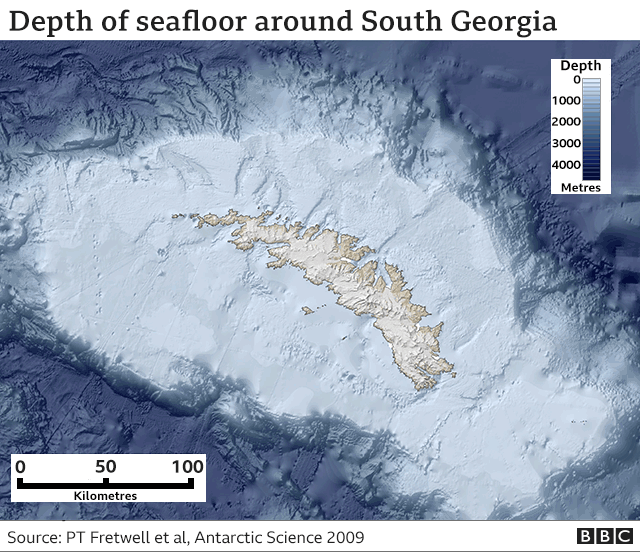

If it grounds there in the shallows, it could cause immense problems for the British Overseas Territory's wildlife.

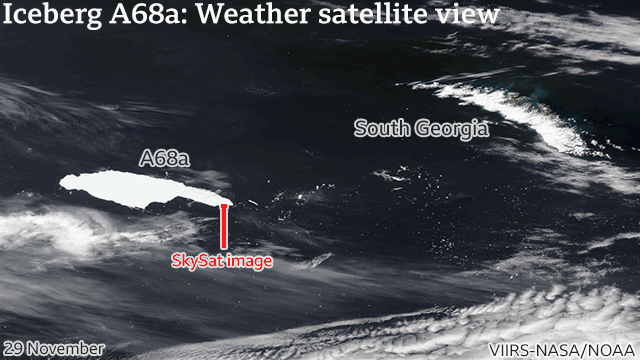

This context image comes from the American polar-orbiting weather satellite Noaa-20

The detailed new picture comes from the San Francisco-based company Planet, external.

It has a fleet of orbiting spacecraft called SkySats that can resolve details at the Earth's surface as small as 50cm across.

It's been a challenge getting a clear view of the 150km-long iceberg because so often it is covered by cloud.

But on Sunday, Planet finally got a beautiful acquisition right over the tip of A68a's "ice finger" (the berg has the shape of a hand with its index finger outstretched, as if pointing).

A68a: A weather satellite sequence from 27 November until 1 December

This movie from the high-orbiting American weather satellite Goes-16 was processed by Dr Simon Proud from Oxford University and the UK's National Centre for Earth Observation (Credit: NOAA/Simon Proud/NCEO)

"The detail of some of the cracks running across the berg are really clear and will be the main controls of the larger bits that break off," explained the British Antarctic Survey's, external Dr Andrew Fleming, who's examined the new picture.

"The edges look really dynamic - including several places where the image seems to have caught the wash as bits have fallen off and collapsed into the sea. It looks more than just waves breaking against the base of the cliffs."

The BAS remote sensing manager continued: "There is an obvious 'ice foot' - essentially an underwater protrusion of the ice that can be seen as lighter-coloured water at the base of the ice cliff in a lot of places. It is very apparent on the main berg at the right side of the image. It is caused by increased melting at the waterline due to wave erosion and warmer surface waters.

"Unsurprisingly, there are huge numbers of smaller bergs. Some bigger fragments have rolled over to expose a cross section of the berg - I can almost make out layers in the ice. But it's not full thickness - they only measure about 60m."

Iceberg A68a is now living on the ragged edge

It might be possible, said Dr Fleming, to gauge the current draft of A68a from the height of its cliffs and the position of shadows. When measured by satellites back in 2017, the draft - the depth of ice below the waterline - was calculated to be roughly 200m.

This gave A68a quite a thin profile by the standards of some Antarctic bergs. Imagine something wide, flat and thin - not unlike a credit card. The fact that the block has been able to maintain much of its bulk for so long in the open ocean has therefore surprised many observers. When it calved from the Larsen C Ice Shelf on the Antarctic Peninsula, it had a surface area a little over 5,800 sq km. About 70% is still intact.

What happens next is anyone's guess. For the moment, the 4,200-sq-km berg is travelling in a stream of water known as the Southern Antarctic Circumpolar Current Front.

When this hits the continental shelf at South Georgia (the coast is 250km away), the berg may well turn with the front and scoot around the southern edge of the island, before then spinning north.

Scientists will be watching to see if A68a's keel gets stuck on the seabed at any point, anchoring it in position.

Should that happen, it would present an enormous obstacle to South Georgia's penguins and seals as they go out to forage - especially if the berg becomes stuck in position for a number of years.

With a draft of about 200m, A68a has the potential to catch on the shallow shelf around the island

The iceberg is now about 250km from the coast of South Georgia

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external