Giant Antarctic iceberg A68a is not done yet

- Published

See how the keel of the giant iceberg has changed over time

It might have suffered a big break-up this week, but the iceberg A68a is still carrying substantial bulk.

The latest satellite analysis indicates this Antarctic colossus maintains a thickness that could yet see it catch in the waters surrounding the South Atlantic island of South Georgia.

If that happens, then worries about the effects the berg could have on the territory's wildlife will resurface.

Penguins and seals might be obstructed as they forage for fish and krill.

And these predators need to feed not only themselves, but their young as well. South Georgia is entering peak breeding season.

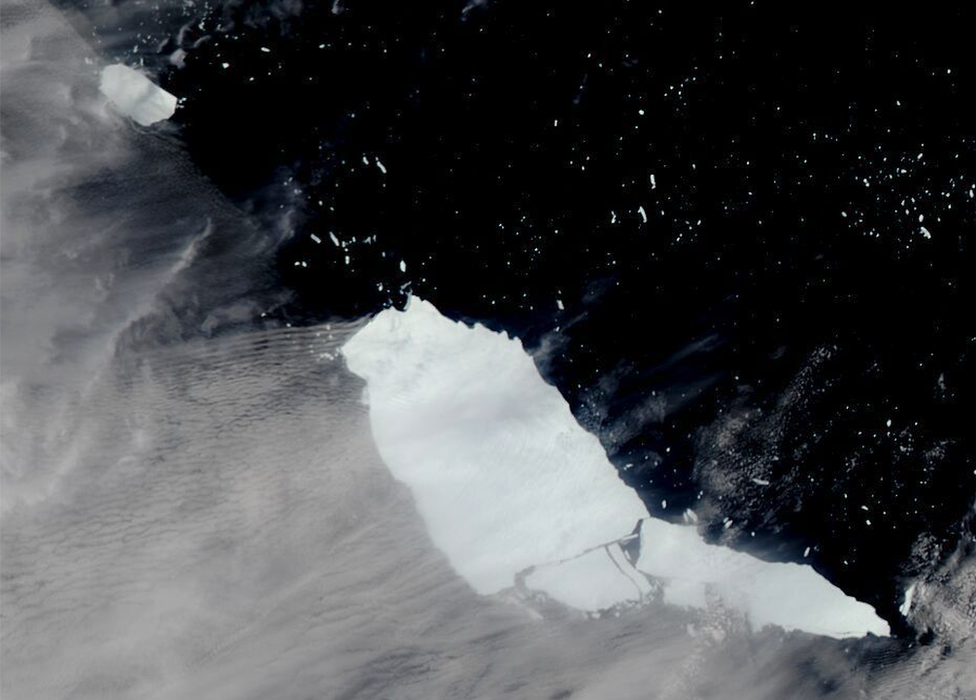

The Royal Air Force flew another sortie over A68a on Monday to assess the situation. This page features video and stills from this reconnaissance mission.

The RAF flew over the iceberg as it moved around South Georgia

The military flight occurred just after a new chunk, A68d, broke from the main block - but before the major fragmentation event on Tuesday.

This saw A68a split into three substantial segments.

What had looked like "a pointing hand" snapped its "index finger and knuckles".

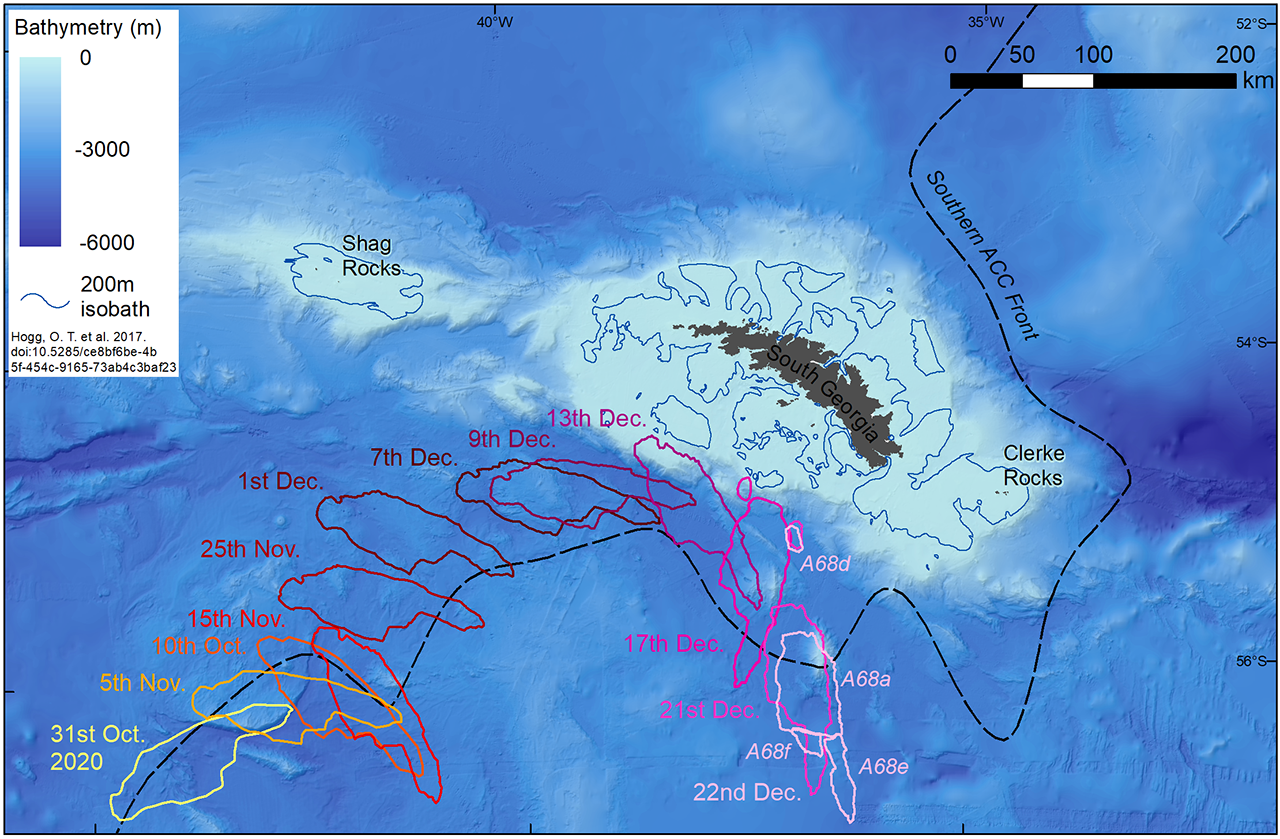

The breakages occurred along predictable lines of weakness that have been evident ever since the berg fist calved from Antarctica in 2017.

Staff at the Nerc Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling (CPOM) at the University of Leeds, UK, have examined A68a's changing shape over its three-and-a-half-year history.

They've used four separate satellite systems to examine not just the evolving area of the frozen block but its thickness, too.

A68a: The "knuckles" and the "index finger" snapped off on Tuesday

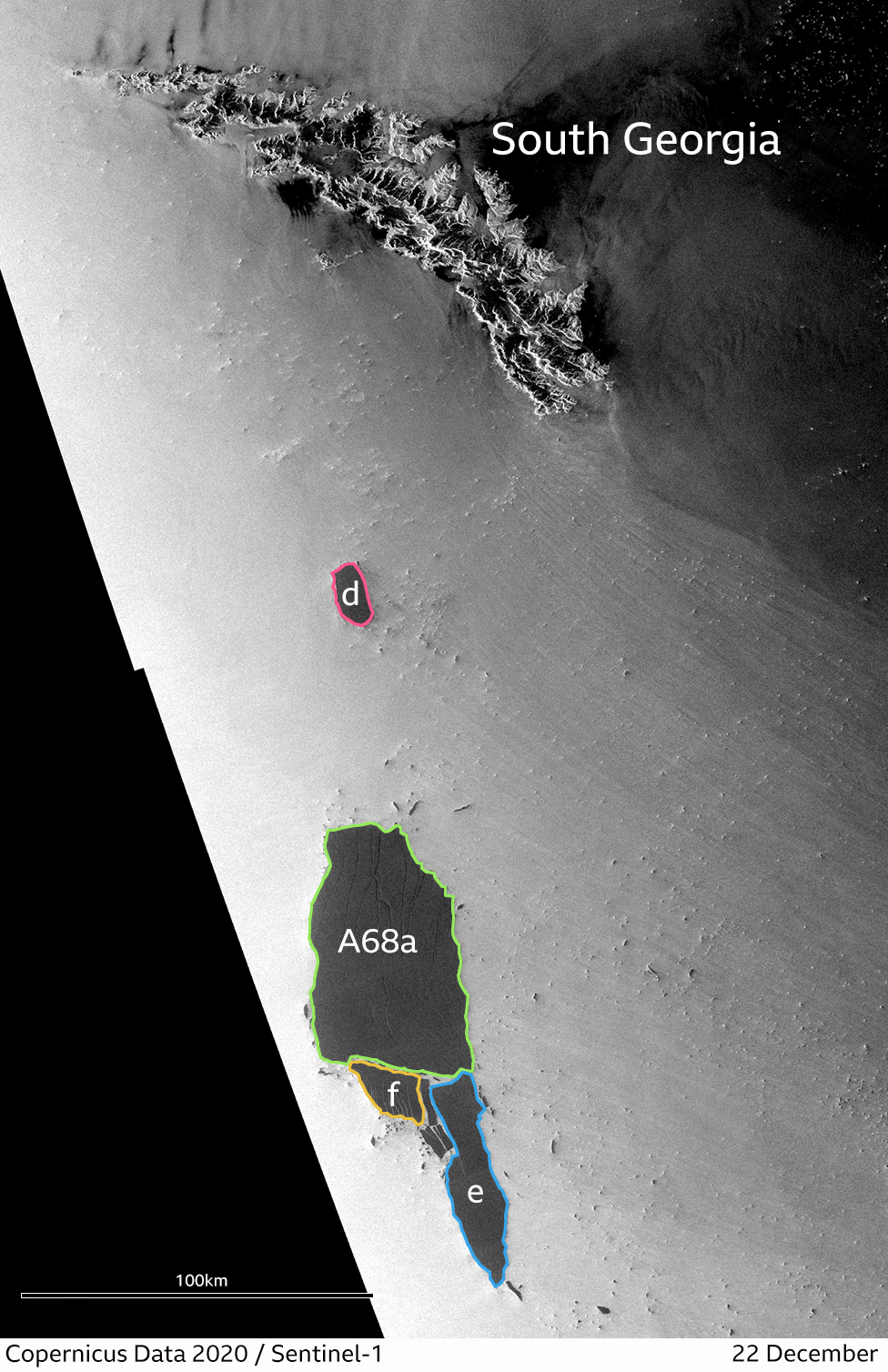

The area was tracked using Europe's Sentinel-1 satellite and America's Modis imager.

What started as a behemoth measuring 5,664 sq km (that's roughly a quarter of the area of Wales) is now down to just 2,606 sq km (about the size of the English county of Durham).

Profiles of the iceberg's height above the surface of the ocean have also been recorded by Europe's CryoSat-2 and America's IceSat-2 spacecraft. Knowing a berg's freeboard enables scientists to calculate its draught - that hidden part below the waterline.

When it first calved from the Antarctic, A68 was 232m thick on average, with its thickest section having a dimension of 285m.

Today, the remnant A68a is 32m thinner in general, although there are places where the thickness has been reduced by over 50m.

When combined, the change in area and thickness amount to a 64% reduction in the iceberg's volume - from the original 1,467 cu km to today's 526 cu km.

It's now three-and-a-half years since A68 calved from Antarctica

Lines of weakness in A68a are gradually being opened up

The big question, of course, is whether the much reduced iceberg still has the capacity to ground itself at South Georgia.

With a still existing submerged keel of 206m at its thickest point, this remains a real possibility.

At the moment, all the berg's many fragments are entrained in a fast-moving stream of water known as the Southern Antarctic Circumpolar Current Front. This is likely to sweep the chunks around South Georgia and then throw them north.

Satellites will monitor their progress as they skirt the shallow continental shelf. There are a number of locations where large ice blocks could get caught and anchor in place.

Interestingly, the measured thickness of the two major fragments that broke free from A68a on Tuesday - they're called A68e and A68f - are thinner by about 50m. This would potentially allow them to get much closer in to the island's coastline.

The submerged bench is known as "iceberg foot". It introduces buoyancy stress that aids break-up

23 December: The Modis imager on Nasa's Aqua satellite views the "broken finger"

A lot has been said about the difficulties a large object sitting offshore would present to foraging marine predators. But there are other implications of note, including the introduction of a mass of freshwater to the ecosystem as a stationary berg melted out over several months.

The CPOM team has even had a go at calculating this input.

The group says the average melting rate of A68 has been 2.5cm per day, and the berg is now shedding 767 cu m of freshwater per second into the surrounding ocean - equivalent to 12 times the outflow of England's River Thames.

For those who have followed A68a on its long journey from the Antarctic into the South Atlantic, Tuesday's significant fragmentation event had been a long time in coming.

Commentators have been surprised by the berg's longevity

Many observers had predicted it would happen months ago.

And we may yet be treated to a much more spectacular disintegration of the remaining elements of A68.

As the blocks move into warmer and warmer air conditions, copious meltwaters will be generated at the surface of the ice. These waters will then force their way down through cracks to open up the ice still further.

There may come a point where what remains of A68a lets go in one catastrophic moment.

The CPOM analysis was conducted by Anne Braakmann-Folgmann and Jamie Izzard.

Caught in the moment of another cliff collapse

Why A68a has little to do with climate change

The iceberg came from a part of the Antarctic where it is still very cold - the Larsen C Ice Shelf. This is a mass of floating ice formed by glaciers that have flowed down off the eastern side of the Antarctic Peninsula into the ocean. On entering the water, the glaciers' buoyant fronts lift up and join together to make a single protrusion. The calving of bergs at the forward edge of this shelf is a very natural behaviour. The shelf will maintain an equilibrium and the ejection of bergs is one way it balances the accumulation of mass from snowfall and the input of more ice from the feeding glaciers on land. Larsen C calves big icebergs like A68 on decadal timescales.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external