Branson's rocket team go 'bonkers' with delight

- Published

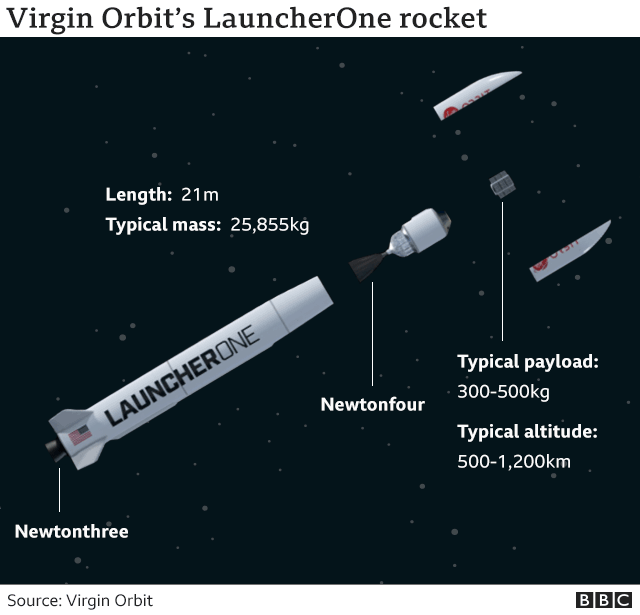

Watch: Virgin Orbit's LauncherOne rocket blasts its way to space

For three hours on Sunday, Sir Richard Branson sat glued to a computer live stream that showed his rocket company try once again to get to orbit.

He was on his Necker Island retreat in the Caribbean; they were flying out over the Pacific, attempting to demonstrate how you could deliver satellites to space using a booster released from under the wing of a jumbo jet.

It was around 19:50 GMT that success was confirmed. Ten shoebox-sized spacecraft had been taken high above the Earth.

Sir Richard's company, Virgin Orbit, immediately sent out a tweet to say everyone not on console at mission control was going "bonkers" with delight, external.

For the British entrepreneur, the feeling was exactly the same - but with a huge amount of relief mixed in there as well. A previous attempt to get to space in May last year had failed, and so it was vital this mission came through.

"If it had gone wrong - and sometimes these things go wrong four, five, six times in a row - it would have been very, very, very expensive for the Virgin Group, at a time when all our airlines are grounded, our cruise companies are grounded and fitness clubs, and so on. So there was quite a lot riding on Sunday's flight being successful," Sir Richard told BBC News.

It was the second attempt to get the LauncherOne rocket to orbit

Now, he can look forward to the future with confidence. Long Beach, California-based Virgin Orbit, external is in the vanguard of start-ups that will service a rising tide of small satellites.

There's been a revolution in robust, miniaturised, low-cost components thanks to the consumer electronics market, and it means pretty much anyone can now build a capable and affordable spacecraft in a very small package.

The major hurdle, as has always been the case, is securing a timely ride to space at a sensible price.

This is where the new dedicated small-sat launcher systems come in. And by getting out in front of all the wannabes, Virgin Orbit can plant strong roots.

"There are a lot of renderings out there; a lot of artists have been employed," Orbit's CEO Dan Hart says when he surveys the rocket start-up scene. "It takes quite a bit to get to orbit, as we've felt these last few years; there's quite a barrier to entry. But, of course, there will be competition."

Sir Richard and investors have spent hundreds of millions of dollars on the project

Hart, though, believes he has something unique to offer. By launching rockets from under the wing of a plane means in theory the Virgin system can operate anywhere in the world. The architecture has a certain flexibility not enjoyed by ground-launched rockets and their fixed pads.

The Virgin Orbit system can be taken direct to the customer; the 747 platform can fly to beat unfavourable weather; and if need be it can send up satellites beyond the sight of prying eyes - something the US DoD and UK MoD have clocked.

"The British government, the US Air Force, the Canadian government, the French government - they've all approached us because they're worried that if satellites get knocked out by a foreign power they won't be able to replace them for months and months. So they're excited that 747s can be parked around the world with satellites, waiting to replace other satellites quickly," explains Sir Richard.

We say "in theory" when talking of multiple launch locations because wherever Virgin Orbit goes it will need approvals - first, to be allowed to take its sensitive technology out of the USA, and, second, to show it can meet the safety and environmental standards required in the operating locality.

Artwork: Realistically, it's probably going to be next year before Cornish launches begin

At the moment, this all holds for California and an area just off the US state's Pacific coastline. But the island of Guam in the central Pacific will soon host a launch; and then it's just a matter of time before we see a launch from the UK.

Sir Richard and his team want to run their converted Virgin Atlantic jumbo out of Newquay airport in Cornwall. There's a lot of talk about trying to make this happen in time for the 47th G7 summit in June, also to be held in Cornwall - "wouldn't it be nice if we could", the businessman says.

In truth, the maiden flight from Britain will most probably have to wait until next year, precisely because of those regulatory demands.

"It's looking like the summer that we'll have those regulations come out and then we'll be applying for a licence to operate," Melissa Thorpe, interim head of Spaceport Cornwall, told BBC News. "Right now, we're just preparing behind the scenes so that we don't waste any time; we want to get to that first launch as soon as possible."

Newquay will be doing some strengthening works to the taxiways and apron at the airport to better withstand the weight of a rocket-carrying jumbo, and will also be building satellite integration facility at its onsite aerohub business park. But the facilities are well set up even now to begin launches.

The desire to use Cornwall isn't driven by sentimentality on the part of Sir Richard. UK companies pioneered many of the approaches that now underpin the small satellite revolution. Those companies ought to be major customers for Virgin Orbit.

"There's a lot going on in the UK in spacecraft development," says Dan Hart. "But there's so much that can be done in science and education - as well as in really driving the economy. And they're obviously going to make some big moves that will affect Cornwall.

"A whole ecosystem will form around that. Kids who would have never thought that they could be a space engineer on a launch programme or on a satellite will all of a sudden see it happening down the street, and it will change the dynamic for them."