SpaceX: World record number of satellites launched

- Published

Watch: Rocket launch containing record breaking number of satellites

A new world record has been set for the number of satellites sent to space on a single rocket.

The 143 payloads, of all shapes and sizes, rode to orbit on a SpaceX Falcon rocket that launched out of Florida.

The number beats the previous record of 104 satellites carried aloft by an Indian vehicle in 2017.

It's further evidence of the major structural changes taking place in space activity that are allowing many more actors to get involved.

This shift is the result of a revolution in robust, miniaturised, low-cost components - many taken direct from consumer electronics such as smartphones - that mean pretty much anyone can now build a capable satellite in a very small package.

And with SpaceX offering to transport those packages to orbit for just $1m, the commercial opportunities will continue to open up.

Guatemala's Santa María volcano: Planet is imaging the entire Earth daily with its Dove satellites

SpaceX itself had 10 satellites on the Falcon - the latest additions to its Starlink telecommunications mega-constellation, which is going to deliver broadband internet connections around the globe.

San Francisco's Planet company had the most satellites of all on the flight - 48.

These were another batch of its SuperDove models that image the Earth's surface daily at a resolution of 3-5m. The new spacecraft take the firm's operational fleet now in orbit to more than 200.

"Internet of things": SpaceBees will connect to all manner of objects on the ground

The SuperDoves are the size of a shoebox. Many of the other payloads on the Falcon rocket were little bigger than a coffee mug, however; and some were smaller even than a paperback book.

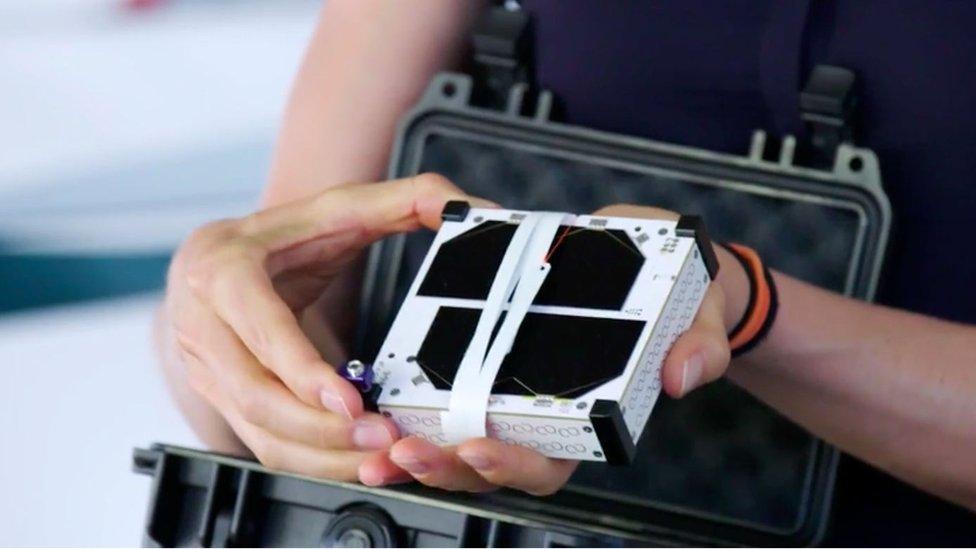

Swarm Technologies is rolling out what it calls the SpaceBees. They're just 10cm by 10cm by 2.5cm.

They'll act as telecommunications nodes to connect devices that are attached to all manner of objects on the ground, from migrating animals to shipping containers.

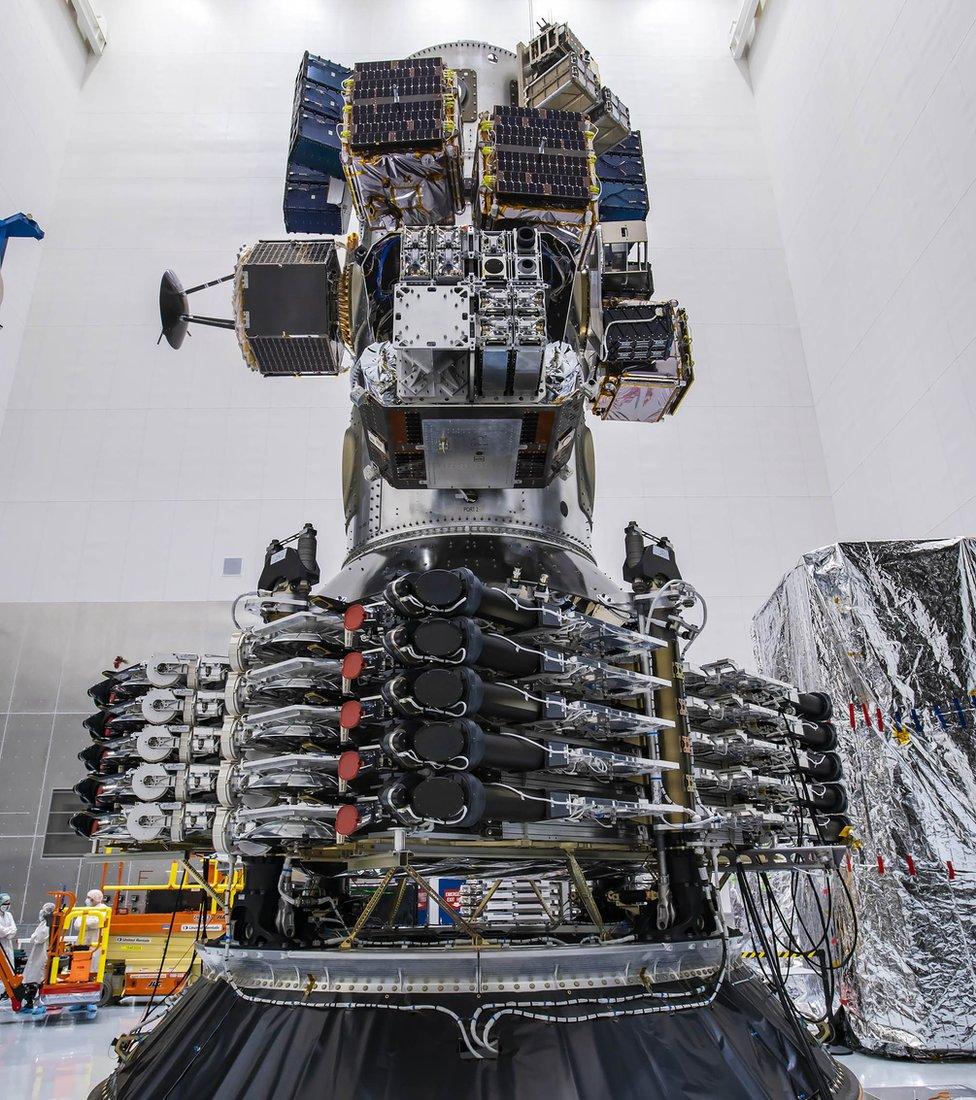

The satellites were mounted on a dispenser that ejected them in sequence

Some of the larger items on the Falcon rocket were suitcase-sized. Among these were several radar satellites. Radar has been one of the major beneficiaries of the revolution in componentry.

Traditionally, radar satellites were big, multi-tonne objects that cost hundreds of millions of dollars to fly, which essentially meant only the military or major space agencies could afford to operate them.

But the adoption of new materials and compact "off the shelf" parts have dramatically shrunk the size (to under 100kg) and price (a couple of million dollars) of these spacecraft.

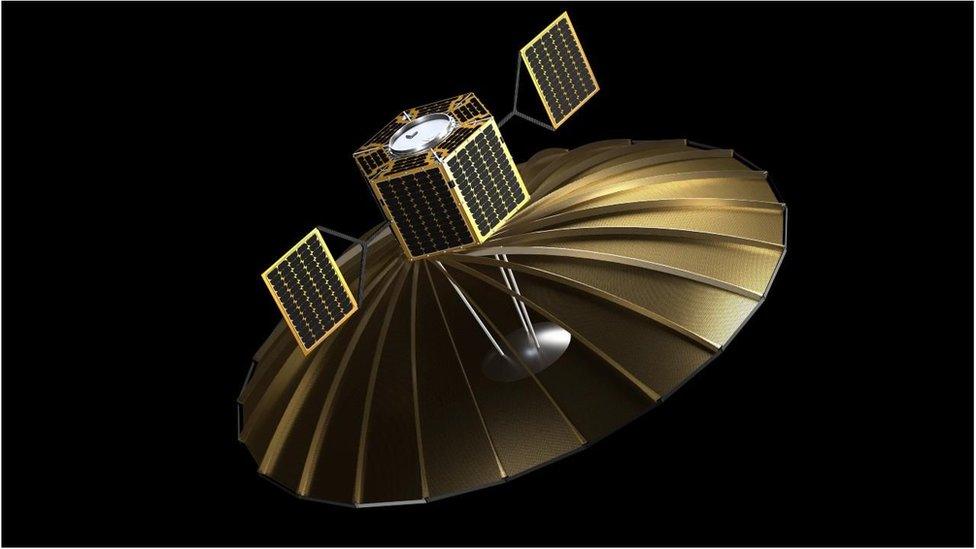

iQPS artwork: The radar satellites unfurl large antennas once they are in space

Iceye from Finland, Capella from the US, and iQPS of Japan all took the ride to orbit on Sunday. These start-ups are establishing constellations in the sky that will return rapid, repeat imagery of the Earth.

Radar has the advantage over standard optical cameras of being able to pierce cloud, and to sense the Earth's surface whether it is day or night. We're entering an age when any change on the planet, wherever it happens, will be picked up almost immediately.

The Falcon carried the 143 satellites into a 500km-high path that runs from pole to pole. This is one of the drawbacks of a big rideshare mission: you go where the rocket goes, and for some that might not be ideal.

A number of satellite missions will want an orbit that's higher or lower in the sky, or on a different inclination to the equator.

This can be achieved by mounting the satellites on "space tugs" which, after coming off the top of the rocket, modify the final parameters for their "passengers" over the course of several weeks. Sunday's Falcon carried two such tugs.

But for some missions a bespoke ride is going to be the only satisfactory solution. It's why we're now witnessing a rush to produce small rockets that can run dedicated flights.

Watch: Virgin Orbit's LauncherOne rocket blasts its way to space

These smaller rockets will not be able to compete on cost with the big vehicles, such as SpaceX's Falcon-9, but they should attract the custom of those with very specific or urgent needs.

Dan Hart, the CEO of Virgin Orbit, which has developed a small rocket that can be launched from under the wing of a Boeing 747, says the start-ups are becoming more discerning.

"These small satellites used to be points of fascination and interest, and it was a case of finding the cheapest way possible to get into space," he explained.

"That's rapidly changing. These are now businesses with critical missions that risk losing revenue if they have to wait on others or go into an unsuitable orbit. And that's why you're going to see people who will pay that little bit more to get to where they want to go when they absolutely need to go there," he told BBC News.

Will Marshall: "Our satellites 'phoned home' and they are healthy"

With the roll call of satellites going into orbit now accelerating rapidly, the issue of traffic management is becoming a hot topic.

Full-on collisions are currently rare, but a surprisingly large number (10%) of satellites will even now experience sudden, unexpected momentum changes, most probably the result of being hit by some small fragment from a previous mission.

The space sector needs to find smarter ways to track objects in orbit and to command timely avoidance manoeuvres, otherwise certain altitudes could ultimately become unusable because of the presence of dangerously dense debris fields.

Jonathan McDowell from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics is a noted historian of astronautics.

He commented: "There are now over 3,000 working satellites in orbit. The number of satellites launched last year at over 1,200 is over twice as many as in any previous year. And the ones launched today - that used to be the number you'd launch in a whole year. So it's getting really crowded up there."

Will Marshall, the CEO of Planet, said his company, and indeed all of the companies on Sunday's flight, were accutley aware of the issue.

"We are seeing crowded areas in certain orbits," he told BBC News.

"Most of the crowded piece that is in danger of what they call Kessler Syndrome (runaway collisions) is quite high up. So one of the tricks that all of these satellites that were launched today use is to just stay really low where there's still a lot of atmospheric drag and eventually those satellites just come down."