Then and now: A 'megadrought' in California

- Published

In our monthly feature, Then and Now, we reveal some of the ways that planet Earth has been changing against the backdrop of a warming world. Here, we look at the effects of extreme weather on a crucial reservoir that supplies water to millions of people in northern California.

This year is likely to be critically dry for California., external Winter storms that dumped heavy snow and rain across the state are not expected to be substantial enough to counterbalance drought conditions.

Lake Oroville plays a key role in California's complex water delivery system.

This 65km-square body of water north of Sacramento is the second-largest reservoir in California.

Not only does Lake Oroville store water, it helps control flooding elsewhere in the region, assists with the maintenance of water quality and boosts the health of fisheries downstream.

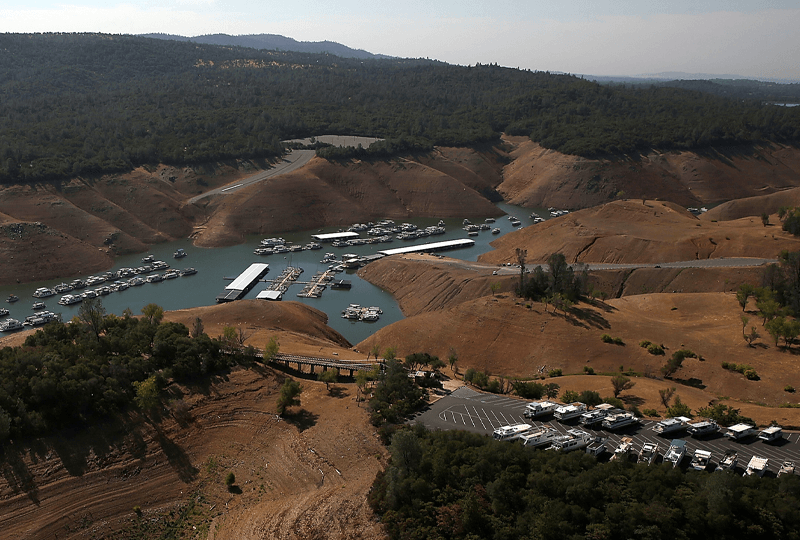

In 2014, more than 80% of California was in the grip of an "extreme drought". Against this backdrop, Oroville's capacity fell to 30% - a historic low level.

As the water level receded to hundreds of feet below normal levels, ramps and roads no longer reached the water's edge.

More worryingly, the reservoir - when full - provided enough water for an estimated seven million households, as well as providing power for hydroelectricity facilities and irrigation for agricultural land.

'Unusually destructive'

The dry conditions didn't start in 2014, however, there had been a drought for years prior to Oroville recording its historic low level.

Indeed, the US space agency's Earth Observatory had warned that the multi-year drought was having a wider impact on the region. Among its effects was a contribution to "unusually active and destructive" fire seasons and poor yields from agricultural land.

"There is strong evidence from climate models and centuries of tree ring data that suggest about one-third to one-half of the severity of the current drought can be attributed to climate change," observed Benjamin Cook, a climate scientist from Nasa's Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York.

Agency scientists added that the data suggested a "megadrought" might already be underway in this region - and that it could last for decades.

The latest update from the US Drought Monitor in December 2020, showed that much of the country's western states were gripped by extreme or exceptional drought, with Nevada, Utah, Arizona and New Mexico, Colorado and western Texas being the worst affected.

The emergency spillway at the dam was predicted to collapse

The Drought Monitor releases maps showing the parts of the country with prolonged shortages in the water supply. It is produced jointly by the National Drought Mitigation Center (NDMC) at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa), and the US Department of Agriculture (USDA).

From one extreme...

Climate change is not just about a warmer world, it also means that the planet will see more extreme environmental conditions and weather. So, for example, episodes of flooding will increase, as well as episodes of droughts.

Lake Oroville was a perfect illustration of how these extremes can threaten our existing infrastructure.

While the lake's levels reached a historic low in 2014, the reservoir's vast embankment dam - the tallest in the US - was pushed to breaking point in February 2017.

Following fierce storms in the surrounding mountains, water was flowing into the lake at a rate of roughly one-and-a-half Olympic-size swimming pools each second.

What went wrong with US dam?

Communities downstream had been evacuated, with more than 100,000 people being ordered to leave their homes.

Officials were struggling to allow water to flow out of the lake because the main spillway - a structure that provides controlled releases of water - and the emergency spillway had been eroded and damaged.

Yet they had to continue sending water down the valley because the reservoir was reaching capacity and there was a sense that there could be a "catastrophic failure" in the structure.

In the space of two years, the lake went from an unprecedented low to a capacity that had not been experienced before. Water cascaded over the emergency spillways, which had not previously been required.

Traditionally, the lake was replenished by meltwater from a thawing snowpack in surrounding mountains, whose river systems fed the reservoir. June was the month when the reservoir was expected to reach its yearly maximum level.

However, in 2017, it was rain that caused the intense water flow. The reservoir had reached capacity in February, rather than the middle of the year, as usually happened.

Scientists again suggested that the event fitted into the paradigm of a warming world.

Speaking at the time to the Guardian newspaper, Prof Roger Bale, from the University of California Merced, explained: "With a warmer climate, we get these winter storms, which dump rain rather than snow."

California Department of Water Resources officials closely monitored the cascade over the reservoir's damaged spillway

The United Nations Environment Programme (Unep) said that the "frequency and intensity of droughts, storms and extreme weather events are increasingly likely above 1.5C (above pre-industrial levels)".

Failure to keep the global average temperature rise to below 1.5C, as outlined in the 2015 Paris climate agreement, is likely to result in more of the world's reservoirs or flood defences being tested to breaking point.

This is a stark warning for world leaders, who will be gathering once again this year at the UN's annual climate summit (COP26) - to be held in Glasgow.

The meeting, which had to be postponed by a year because of Covid, will seek to raise global ambition on tackling climate change - with a view to keeping temperature rise within the 1.5C limit.

Our Planet Then and Now will continue up to the UN climate summit in Glasgow, which is due to start in November 2021

Related topics

- Published13 February 2017