Climate change: 'Forever plant' seagrass faces uncertain future

- Published

The green, underwater meadows of Posidonia seagrass that surround the Balearic Islands are one of the world's most powerful, natural defences against climate change.

A hectare of this ancient, delicate plant can soak up 15 times more carbon dioxide every year than a similar sized piece of the Amazon rainforest.

But this global treasure is now under extreme pressure from tourists, from development and ironically from climate change.

Posidonia oceanica is found all over the Mediterranean but the area between Mallorca and Formentera is of special interest, having been designated a world heritage site by Unesco over 20 years ago.

Here you'll find around 55,000 hectares of the plant, which helps prevent coastal erosion, acts as a nursery for fish, but also plays a globally significant role in soaking up CO2.

"These seagrass meadows are the champion of carbon sequestration for the biosphere," said Prof Carlos Duarte, of the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia.

He's recently published the first global scientific assessment of the environmental value of Unesco's marine world heritage sites, external.

"Posidonia acts as a very intensive sediment trap and captures carbon into these sediments. It is also very resistant to microbial degradation, so the carbon is not degraded when it's deposited on the sea floor. And much of that stays unaltered during decades to millennia."

Depending on the water temperature, the species reproduces either sexually through flowering or asexually by cloning itself. This ability to clone itself means it can live an extremely long time.

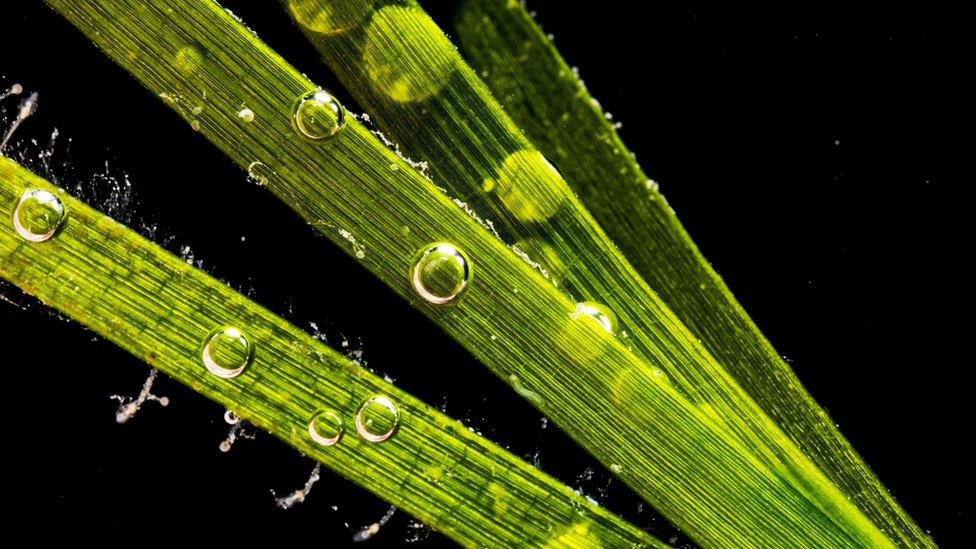

Seagrasses are plants with amazing abilities to soak up carbon

"It's a remarkable plant not only in the capacity to sequester carbon, but also because it's one of the longest-lived organisms on the planet," said Prof Duarte.

"In the marine protected areas of Ibiza we documented one clone where we estimated that the seed that produced that clone was released into the seafloor and sprouted 200,000 years ago."

"A clone could be eternal, kind of," says Dr Núria Marbà, from the Mediterranean Institute for Advanced Studies in Mallorca.

"If there are no damages that disturb it, it could last for forever - well maybe not forever but for an incredibly long time."

But despite its ability to live almost infinitely, Posidonia is finding the modern world increasingly treacherous.

This vivid green carpet that extends under the seas in the Balearics faces an ongoing threat from boats dropping their anchors which crush, tear and destroy the meadows.

One study showed that between 2008 and 2012, Posidonia meadows in Formentera were reduced by 44% because of the impact of anchoring.

Oxygen bubbles on a seagrass plant

The plant also grows extremely slowly.

The damage caused by one yacht's anchor in a single day several years ago would take almost 1,000 years to restore.

Another threat comes from too many nutrients in the waters, caused by effluent released from water treatment sites across the islands.

But perhaps the biggest and most difficult challenge for Posidonia is climate change.

"Posidonia has an upper thermal limit of about 28C," says Dr Marbà.

"I think it's about half of the summers since 2000 that we have exceeded this temperature in the water in the Balearic Islands.

"It doesn't cause massive mortality. But it's excessive for the slow growth of the plant."

Seagrass meadows off the coast of Western Australia

So what can be done to help protect this amazingly powerful seagrass?

Government action to protect Posidonia in the Balearics has been ramped up in recent years and public awareness of the importance of the species is rising.

But some researchers believe that putting a financial value on the carbon that's locked up by Posidonia could release the funds to save it.

"As countries try and reach the goals of the Paris agreement, the forecast is that carbon credits are going to see a tenfold increase in value," said Prof Carlos Duarte.

"Therefore, there's likely to be an increase in investment in habitats like Posidonia that can lock up carbon and generate these credits."

This would be welcome news in Ibiza and Formentera. If the carbon that's already been sequestered by the seagrass increases in value, then it will pay to protect and even attempt to restore the Posidonia meadows.

But time and rising temperatures are the key challenge, as Dr Núria Marbà explains.

"The whole thing of planting seagrasses is that you have to do a massive effort at the beginning to start the process. And then you just wait for the plant itself to grow.

"If we are in a hurry, at human timescales, it's impossible.

"But if we don't mind, and we can wait for a few centuries, it will be okay."

Follow Matt on Twitter @mattmcgrathbbc, external.