Space debris removal demonstration launches

- Published

A wet morning launch for the Soyuz at Baikonur

A Soyuz rocket has launched from the Baikonur cosmodrome in Kazakhstan to put 38 different satellites in orbit.

Among the payloads was a 500kg Earth imager developed by the South Korean space agency; and a pair of spacecraft from the Tokyo-headquartered Astroscale company which will give a demonstration of how to clean up orbital debris.

Astroscale's showcase will be run from an operations centre in the UK.

The Soyuz flight lasted nearly five hours following a 06:07 GMT lift-off.

The long duration was a consequence of having to put so many different satellites in three different orbits roughly 500km to 550km above the Earth.

A lot of interest ahead of launch had focussed on the Astroscale mission.

With the space environment becoming increasingly cluttered, there is heightened awareness that something needs to be done to sweep away spaceflight's legacy of discarded hardware.

This debris - of which there is roughly 9,000 tonnes up there - is a potential collision risk to the operational systems that deliver much-needed services, such as weather forecasting and telecommunications.

Watch an animation of how the demonstration should proceed

Astroscale launched what it calls Elsa-D (End-of-Life Service by Astroscale demonstration). The demonstration mission consists of two spacecraft: a 175kg "servicer" and a 17kg "client".

On the Soyuz, the duo were connected, but in the coming weeks they will be commanded to separate to begin a repeating game of cat and mouse.

The servicer will use its sensors to find and chase down the client, latching on to it using a magnetic docking plate, before then releasing "the mouse" for another capture experiment.

The task will become increasingly complex, with the most difficult rendezvous requiring the servicer to grab the client as it's tumbling.

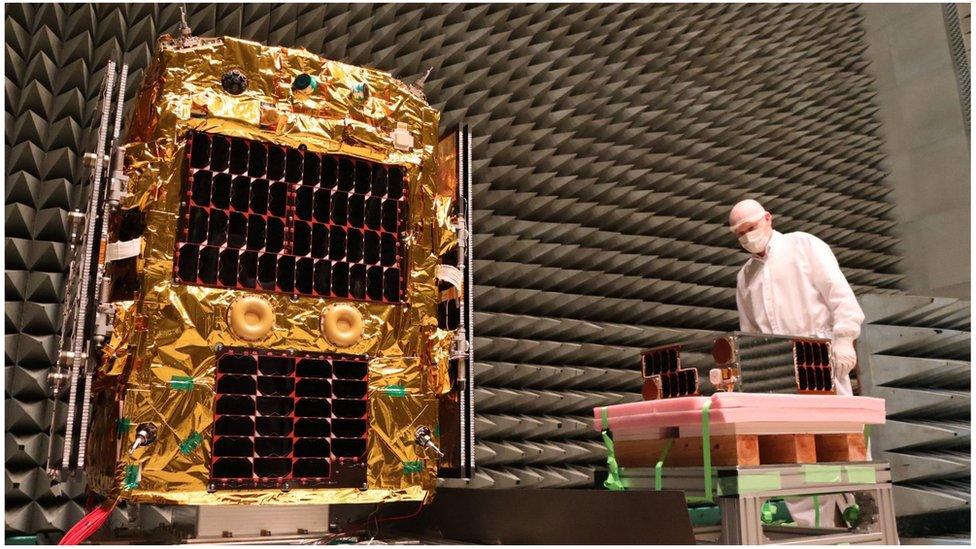

The servicer and client during testing prior to Monday launch

Ultimately, the pair will be commanded to come out of orbit to burn up in the atmosphere.

"The mission simulates a scenario where we would rendezvous with, and dock with, and capture a piece of debris that is free-floating in space," explained Astroscale chief technical officer Mike Lindsay.

"We would then lower the debris, such that it re-enters Earth's atmosphere and stays out of the way of other spacecraft and operations," he told BBC News.

There is a burgeoning waste problem in the volume of space just above the Earth - a few hundred to a few thousand km in altitude.

BBC Crowdscience: Questions about life, Earth and the Universe

The accumulated junk ranges in nature from big rocket segments through to tiny shards of metal that have been created in accidental explosions and collisions. All move with high velocity and are therefore capable of destroying, or at least badly damaging an active satellite, of which there are currently over 3,000.

Precise tracking is possible on debris objects larger than 10cm. There are about 30,000 of these in the catalogue, but there may be one million items out there nearer to 1cm in size that are extremely difficult to monitor.

Spacecraft owners are asked to adhere to guidelines that would see all their retired missions brought out of the sky within 25 years of the end of operations. But compliance is poor, and experts agree we now need to start fetching the bigger pieces of junk and bringing them down - if we want near-Earth orbits to remain useable.

Astroscale wants to offer this as a commercial service.

"In the same way that you call up a breakdown service when your car breaks down on the motorway, the idea is that we can do the exact same thing for space - a space sweeping service which can clean up as we go," said Harriet Brettle, the head of business analysis at Astroscale.

On the design board for future commercial missions is an Elsa-M mission, where the M stands for "multi-client'. In this scenario, the servicer would capture in turn three clients and pull them down into lower orbits where they could more easily re-enter the atmosphere and burn up.

The client spacecraft, or mouse, for this Astroscale demo was manufactured by Surrey Satellite Technology Limited (SSTL) of Guildford.

Two other British-made satellites joined the ride to orbit, both manufactured by Open Cosmos on the Harwell science campus in Oxfordshire - the same location as for Astroscale's mission operations centre.

One of the Open Cosmos platforms is to be used by Lacuna Space, again based at the Harwell Hub. Lacuna is developing an "Internet of Things" (IoT) constellation of small satellites that can link dispersed connected objects on the ground - everything from shipping containers to migrating animals.