Dinosaur-killing asteroid strike gave rise to Amazon rainforest

- Published

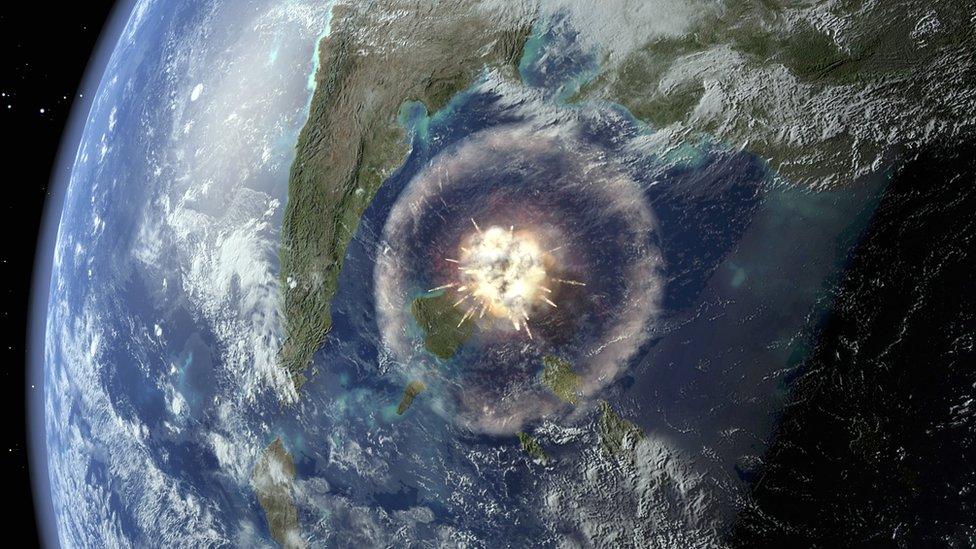

The asteroid impact 66 million years ago led not just to the extinction of dinosaurs, but other forms of life

The asteroid impact that killed off the dinosaurs gave birth to our planet's tropical rainforests, a study suggests.

Researchers used fossil pollen and leaves from Colombia to investigate how the impact changed South American tropical forests.

After the 12km-wide space rock struck Earth 66 million years ago, the type of vegetation that made up these forests changed drastically.

The team has outlined its findings in the prestigious journal Science.

Co-author Dr Mónica Carvalho, from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institution in Panama, said: "Our team examined over 50,000 fossil pollen records and more than 6,000 leaf fossils from before and after the impact."

They found that cone-bearing plants called conifers and ferns were common before the huge asteroid struck what is now the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico.

But after the devastating impact, plant diversity declined by roughly 45% and extinctions were widespread, particularly among seed-bearing plants.

While the forests recovered over the next six million years, angiosperms, or flowering plants, came to dominate them.

Modern tropical rainforests are dense, with thick canopies - unlike those of the late Cretaceous Period

The structure of tropical forests also changed as a result of this transition. During the late Cretaceous Period, when the dinosaurs were still alive, the trees that made up the forests were widely-spaced. The top parts did not overlap, leaving open sunlit areas on the forest floor.

But post-impact, forests developed a thick canopy that allowed much less light to reach the ground.

So how did the impact transform the sparse, conifer-rich tropical forests of the dinosaur age into the rainforests of today, with their towering trees dotted with multi-coloured blossoms and orchids?

Based on their analysis of the pollen and leaves, the researchers propose three different explanations.

Firstly, dinosaurs could have kept the forest from growing too dense by feeding on and trampling plants growing in the lower levels of the forest.

A second explanation is that falling ash from the impact enriched soils throughout the tropics, giving an advantage to faster-growing flowering plants.

The third explanation is that the preferential extinction of conifer species created an opportunity for flowering plants to take over.

These ideas, say the team, aren't mutually exclusive, and could all have contributed to the outcome we see today.

"The lesson learned here is that under rapid disturbances... tropical ecosystems do not just bounce back; they are replaced, and the process takes a really long time," said Dr Carvalho.

- Published25 October 2018

- Published26 May 2020

- Published26 May 2020