Europe will join the space party at Planet Venus

- Published

- comments

You wait ages for a mission to Venus and then three come along at once.

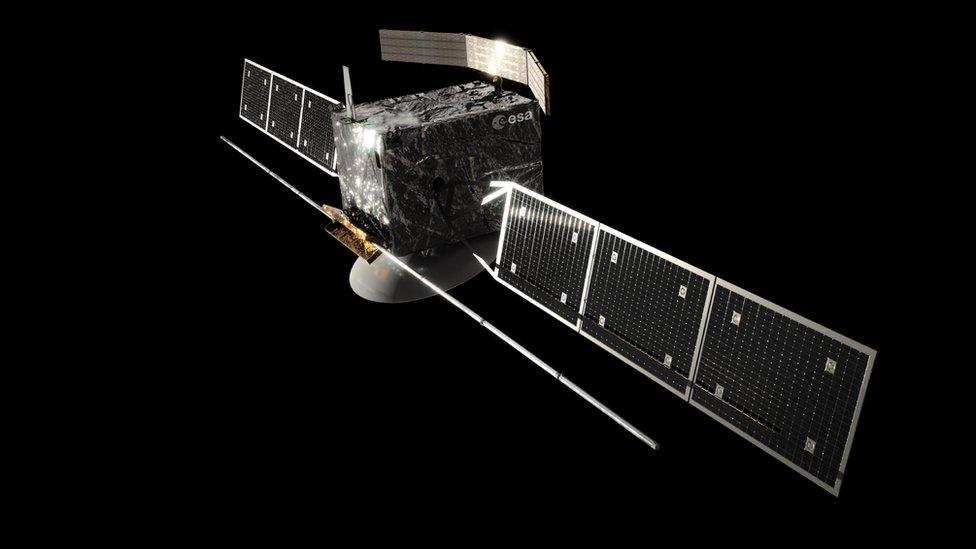

The European Space Agency has just selected a probe called Envision, external to go study the second planet from the Sun.

Esa made the announcement one week after its American counterpart, Nasa, chose two Venus projects of its own, known as Veritas and Davinci+

The destination isn't the only overlap; Europe and the US will both be contributing to each other's efforts in the form of hosted instrumentation.

"All three of the missions are highly complementary," Dr Philippa Mason, an Envision science team-member from Imperial College London, UK, told BBC News.

The trio will start launching from the end of this decade for observation campaigns that run through the early to mid-2030s.

Envision should arrive around 2034/35.

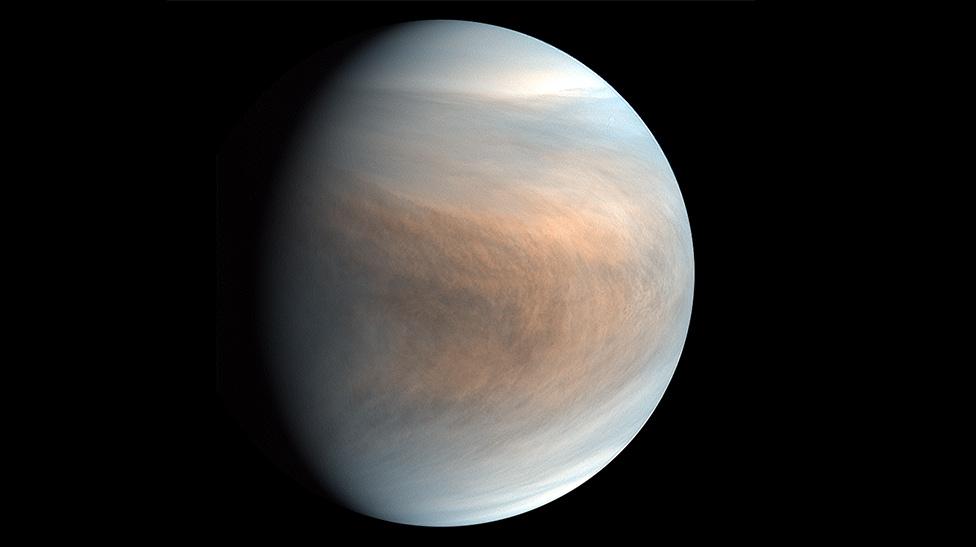

Venus is often described (unfairly) as Earth's "evil twin". Almost the same size as our home planet, it's hellishly hot and dry. It's nothing like the lush blue orb on which we live.

And it's this stark difference that poses the question that all three missions will aim to answer - why so?

Radar will be used to penetrate the opaque clouds of Venus

Dr Colin Wilson from Oxford University, UK, pondered: "Venus is our nearest neighbour and the only Earth-sized planet we can visit.

"It's geologically active, we think. And if that's the case we want to know why Venus didn't turn out like Earth? Or, perhaps, the even better question is: why didn't Earth develop like Venus? How come we got the habitable climate?"

Dr Wilson, who helped scope Envision, said the Esa project would be highly focused in nature.

Whereas the more similar of the two US missions, Veritas, will make global maps, looking for volcanic and other geological activity, the European probe will concentrate on regions that encompass a relatively small portion of the planet.

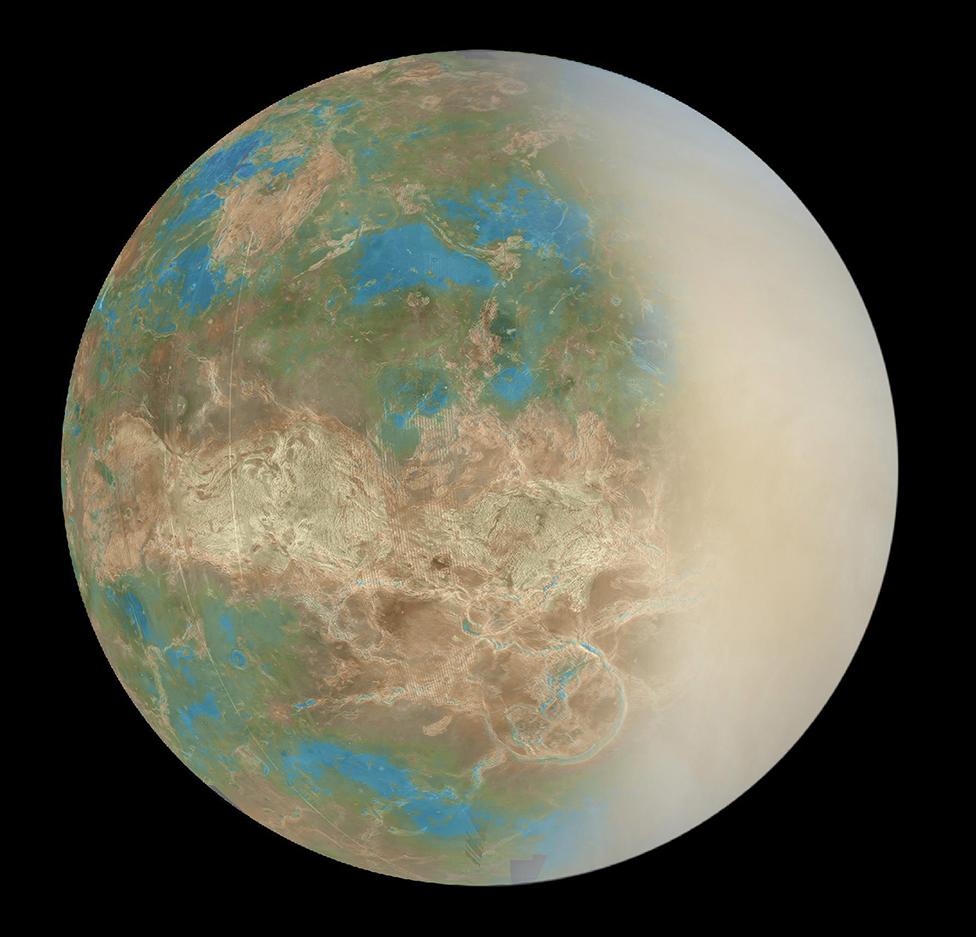

These are the enigmatic "tesserae". They've been described as the Venusian equivalent of Earth's "continents".

They're high and deformed - and, possibly, represent among the oldest terrains on the planet. A major quest for Envision will be to determine their composition.

"If they're made of basalt, that would imply fresh, virgin magma erupting on to the surface everywhere, all of a similar composition," explained Dr Mason.

"But if those 'continents' actually have a very different composition - if they're granitic in nature - that would mean that at some stage in the past there's been water in the mantle of Venus because you make granite from wet magma. Envision will be able to distinguish between granite and basalt - and other flavours of rock."

Artwork: The light beige areas in this rendering are the tesserae

Such a discovery would also say something about tectonics - the great rocky engine that on Earth constantly recycles its outer layers, and helps regulate a habitable climate in the process.

The new wave of Venus missions will go some way to establishing whether, and to what extent, this engine has operated at Venus through history.

Envision will carry six experiments. The principal sensor will be a synthetic aperture radar that will pierce the thick clouds on the planet to map surface features down to a resolution of 10m per pixel.

A second radar will sound below-surface features to a depth of a kilometre.

Three of the remaining four instruments are spectrometers that will look for hotspots on Venus and track gases in its atmosphere.

From previous missions, there are what look to be hundreds of thousands of volcanoes. What the mission team wants to know, however, is how many are still active today.

By going for repeat imaging of restricted regions of the planet, the hope is new lava flows can be detected and measured.

Envision will also have a radio experiment to measure gravity.

It's a complete and carefully constructed package.

"Venus is our only Earth-sized neighbour and yet it could not be more different," observed Prof Richard Ghail from Royal Holloway, University of London, UK, who first proposed Envision in 2010 and is its lead scientist.

"EnVision will probe the links between its atmosphere, surface and interior to discover why Venus is so different, giving us the keys to understanding Earth-sized planets everywhere."

Venus - The same but quite different

It comes as close as 40 million km; it's our nearest planetary neighbour

Just 5% smaller in radius than Earth, the most similar in size and mass

With cloud temperatures near 25C, Venus might appear a benign place

But the surface is 450C and the pressure is 90 times that at Earth

The selection of Envision came during a meeting of Esa's Science Programme Committee.

By all accounts it wasn't a rubber stamp process. Some of the member state delegations in the meeting wanted re-assurance that the science on Envision was sufficiently "synergistic" with the Americans' efforts - that it was properly complementary and not simply a copy-cat exercise.

Envision team-members say these synergies were outlined in their proposal and that the close community that exists among Venus researchers in Europe and the US means that all three missions will work "hand in glove".

Thursday's decision is not quite the full "green light" for the project. Some further feasibility work is required before the agency formally "adopts" the mission, but barring the emergence of some unforeseen technical obstacles or a large, unexpected rise in costs, Envision is now assumed to be "Go!".

The concept falls in Europe's Medium Class series. As such it has a capped budget to Esa of about €550m (£470m; $670m). This pays for the basic chassis of the spacecraft, the launch rocket from Earth and the operations at Venus.

Individual member states supply the instruments. For Envision, this means principally sensor contributions coming from Germany, France, Italy, Belgium and Spain.

The US will provide the synthetic aperture radar (Europe will be contributing to the radar on the American Veritas mission).

Artwork: Tracking down active volcanoes will involve repeat imaging in specific locations

There was a time when the UK was going to provide the radar, based on the Novasar satellite developed by Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd. But high cost and an offer from across the Atlantic meant the Envision design team eventually decided to go with equipment to be built at Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Airbus UK is in a strong position to pull all the equipment together and assemble the final probe.

Interest in Venus spiked recently with the revelation from a group of astronomers that telescopic observations had spied phosphine in the clouds of Venus. This chemical has a potential biological origin, prompting speculation that there could be microbial life at more benign altitudes on the planet.

The persuasiveness of the phosphine observations has receded with further study, but many still regard Venus as a fascinating place to visit.

The rocket entrepreneur Peter Beck, who launches satellites from New Zealand, says he intends to send a mission of his own in 2023.

This would put a probe in the atmosphere to get better information on the composition of the clouds, including to search for the putative phosphine.