Rare black hole and neutron star collisions sighted twice in 10 days

- Published

Artist's impression of a neutron star falling into a black hole

Scientists have detected two collisions between a neutron star and a black hole in the space of 10 days.

Researchers predicted that such collisions would occur, but did not know how often.

The observations could mean that some ideas of how stars and galaxies form may need to be revised.

Prof Vivien Raymond, from Cardiff University, told BBC News that the surprising results were ''fantastic''.

"We have to go back to the drawing board and rewrite our theories," he said effusively.

"We have learned a bit of a lesson again. When we assume something we tend to be proved wrong after a while. So we have to keep our minds open and see what the Universe is telling us."

Five reasons why gravitational waves matter

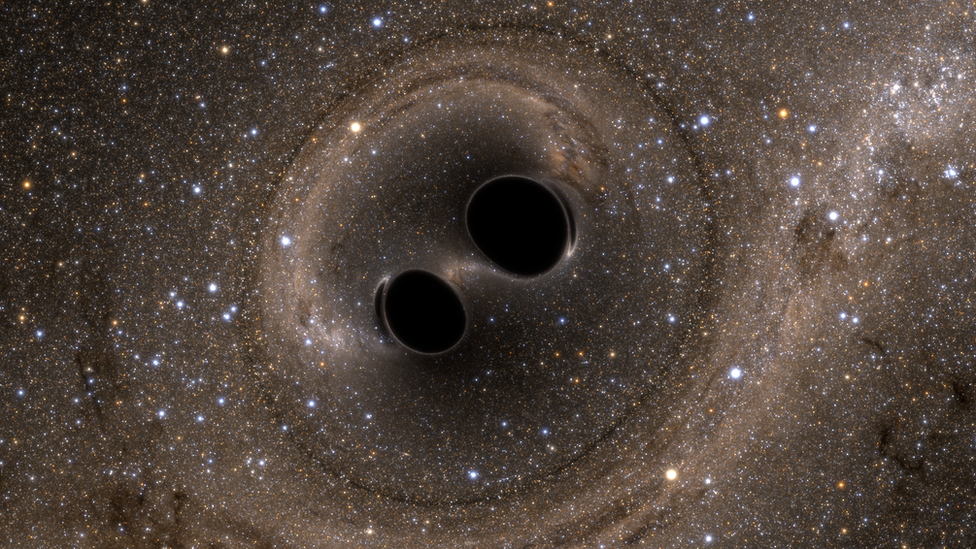

Black holes are astronomical objects that have such strong gravity, not even light can escape. Neutron stars are dead stars that are incredibly dense. A teaspoonful of material from a neutron star is estimated to weigh around four billion tonnes.

Both objects are cosmological monsters, but black holes are considerably more massive than neutron stars.

In the first collision, which was detected on 5 January 2020, a black hole six-and-a-half times the mass of our Sun crashed into a neutron star that was 1.5 times more massive than our parent star. In the second collision, picked up just 10 days later, a black hole of 10 solar masses merged with a neutron star of two solar masses.

When objects as massive as these collide they create ripples in the fabric of space called gravitational waves. And it is these ripples that the researchers have detected.

The researchers looked back at earlier observations with fresh eyes and many of them are likely to to have been similar mismatched collisions.

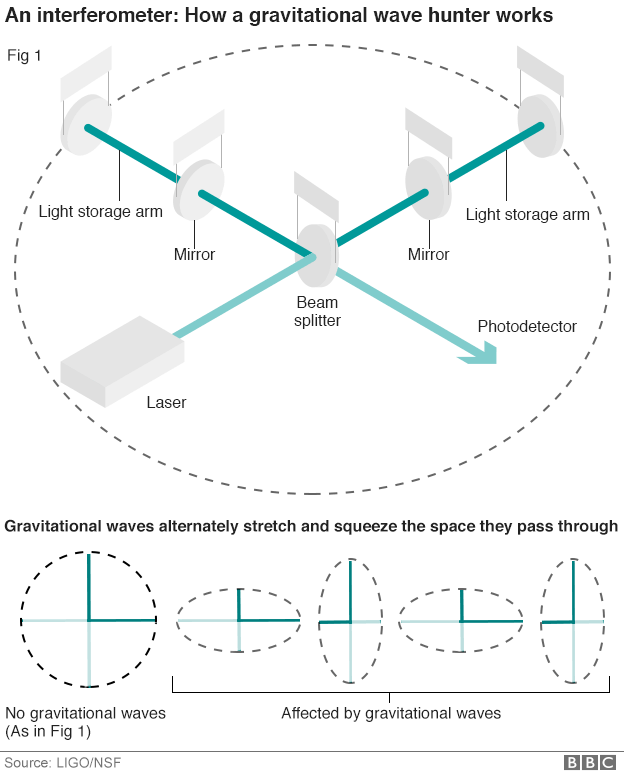

Much of the R&D work necessary for the breakthrough was done at Europe's GEO600 laser interferometer

Researchers have detected two black holes colliding, as well as two neutron stars but this is the first time they have detected a neutron star crashing into a black hole.

So apart from completing the set, why does this latest collision matter?

It is because, according to current theories and past observations, neutron stars tend to be found with - and collide into - other neutron stars. And the same should be true of black holes.

In fact, there are factors which reduce the chances of the two distinct objects being found together.

Science correspondent explains gravitational waves and what their discovery means for science

But the two neutron star-black hole collisions, published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, may challenge that received wisdom.

Instead, it may lean towards another suite of theories, which assume that black holes and neutron stars are indeed found alongside each other. These alternative theories imply that stars and galaxies formed in different ways to the picture painted by standard views of how the cosmos formed.

For example, over billions of years, stars have produced many of the building blocks from which larger cosmic structures - such as planets and galaxies - are formed. The production within stars of so-called heavy elements - such as iron, carbon and oxygen - is related to the proportion of black holes and neutron star pairs in the Universe.

The force with which stars push out the material inside them when they explode is also related to this proportion of black hole and neutron star pairs. In conclusion, the new finding suggests that stars produce fewer heavy elements and push them out with less force than previously thought, which, in turn, has implications for real-world observations of the Universe.

No existing theory can perfectly explain what astronomers see in the night sky. But, according to Dr Raymond, many of the ideas can be ''tweaked'' to better fit what we now know.

Prof Sheila Rowan, of Glasgow University, told BBC News that observations of the type and frequency of collisions of black holes and neutron stars over the past six years is creating an ever more detailed picture of the dynamics inside galaxies.

"All this is giving us a rich picture of stellar evolution. This latest observation is another first for us in our understanding of what is out there in the Universe and how it came to be the way it is," she said.

The collisions were detected by measuring waves caused by the sudden changes in gravitational forces that occur when two massive celestial bodies collide. These are ripples in the fabric of space itself, just like a stone thrown into a still pond.

These so-called gravitational waves travel hundreds of millions of light years across space and were picked up by detectors in Washington State and Louisiana in the US and the Virgo detector in central Italy. Together, they form the Advanced Light Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (ALIGO) collaboration.

Pallab Ghosh explains the sound of the gravitational wave and a computer visualisation

By the time they reach us, the ripples are tiny - less than the width of an atom. The detectors themselves are among the most sensitive instruments ever constructed.

In future, the team hopes to detect neutron star-black hole collisions which are also observed by telescopes - both in space and on the ground. This will enable scientists to find out more about the super-heavy materials neutron stars are made of.

The ALIGO collaboration comprises over 1,300 scientists from 18 countries, and includes researchers from 11 UK universities.

Follow Pallab on Twitter, external.

Related topics

- Published11 February 2016

- Published7 January 2020