Deep sea mining may be step closer to reality

- Published

The Patania II is one prototype of a deep sea mining machine

Are the first mines on the ocean floor getting closer to being a reality?

The tiny Pacific nation of Nauru has created shockwaves by demanding that the rules for deep sea mining are agreed in the next two years.

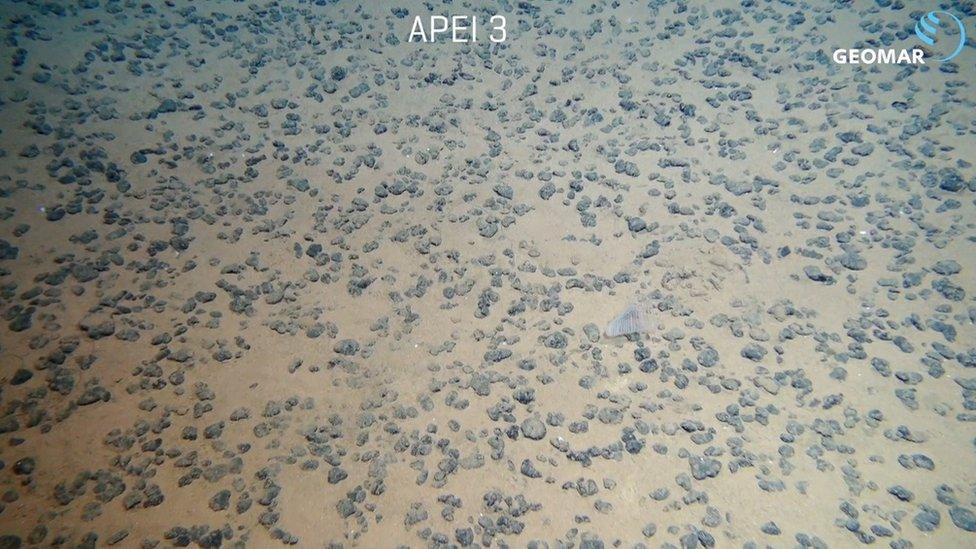

Environmental groups warn that this will lead to a destructive rush on the mineral-rich seabed "nodules" that are sought by the mining companies.

But United Nations officials overseeing deep sea mining say no venture underwater can start for years.

So what's causing concern?

It's all about a letter that refers to the small print of an international treaty which has far-reaching implications.

Nauru, an island state in the Pacific Ocean, has called on the International Seabed Authority - a UN body that oversees the ocean floor - to speed up the regulations that will govern deep sea mining.

It's activated a seemingly obscure sub-clause in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea that allows countries to pull a 'two-year trigger' if they feel negotiations are going too slowly.

Nauru, which is partnered with a mining company, DeepGreen, argues that it has "a duty to the international community" to make this move to help achieve "regulatory certainty".

It says that it stands to lose most from climate change so it wants to encourage access to the small rocks known as nodules that lie on the sea bed.

That's because they're rich in cobalt and other valuable metals that could be useful for batteries and renewable energy systems in the transition away from fossil fuels.

The process has been likened to "potato harvesting" on the sea bed

Why could this matter?

If the ISA does not manage to settle the rules for mining within two years, it may issue Nauru with provisional approval to go ahead - and no one knows what that could mean.

"This could really open the floodgates," Matthew Gianni of the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition told me.

"If Nauru and DeepGreen get a provisional licence, any number of other companies or states could trigger the two-year rule too and then the whole process descends into utter chaos.

"Things have got a lot messier - it would not be a coordinated, well-planned process of negotiation to come up with regulations."

What does the International Seabed Authority say?

In an interview with the BBC, the authority's secretary-general Michael Lodge has played down the implications of Nauru's move, saying that there's still a long way to go before any mining can start.

The Apollo II prototype was tested off the coast of southern Spain in 2019

He said the Council of the ISA had agreed back in 2017 to finalise the regulations for mining by 2020 - a plan that was derailed by Covid-19.

If Nauru and its partner DeepGreen are ready to apply for a mining licence in two years' time, there would then be a series of hurdles before approval could be given - including an environmental impact assessment and plans to minimise the damage.

"Even under the current draft regulations," Mr Lodge told me, "any application for exploitation is likely to be a lengthy process that has multiple checks and balances."

That would take at least two or three years at least so the earliest any actual mining would begin would be around 2026.

Where does this leave the deep ocean?

Scientists say they're far from gaining a complete understanding of the ecosystems in the abyssal plains - but already know they're far more vibrant and complex than previously thought.

The nodules, a habitat for countless forms of life, are estimated to have formed over several million years so any recovery from mining will be incredibly slow.

Also, what's still unknown is the effect of the plumes of sediment that will be stirred up by the giant machines and are likely to drift over vast distances underwater.

Researching this question is a difficult and slow task - and is unlikely to be fully answered within the two-year period initiated by Nauru.

So Andrew Friedman of The Pew Charitable Trusts, is among those fearful of "fast-tracking" the approvals process.

"The seabed is a vast, unexplored, biologically-rich environment, and the ISA must invest the time and resources needed to ensure deep-sea ecosystems are protected before any mining goes forward."

So what's next?

Jessica Battle of WWF says a moratorium is essential to have a proper evaluation of the risks.

"We really need to put a brake on all this, in particular until there's enough time for the science to help make an informed decision."

She's less worried about the prospects of actual mining starting in two years' time - given that mining machines still aren't ready - and more about what might happen in the rush to get the regulations finalised.

"What will prevail? The precautionary principle and care of the environment? Or business interests?"

Follow David on Twitter., external