Companies back moratorium on deep sea mining

- Published

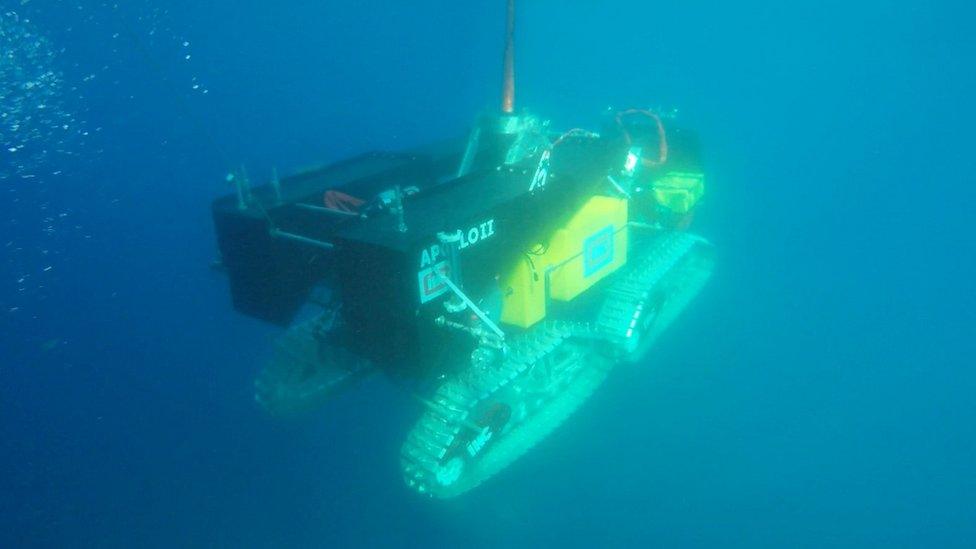

Apollo II is a prototype deep sea mining machine. It was tested off the coast of southern Spain in 2019

A long-running dispute over plans to start mining the ocean floor has suddenly flared up.

For years it was only environmental groups that objected to the idea of digging up metals from the deep sea.

But now BMW, Volvo, Google and Samsung are lending their weight to calls for a moratorium on the proposals.

The move has been criticised by companies behind the deep sea mining plans, who say the practice is more sustainable in the ocean than on land.

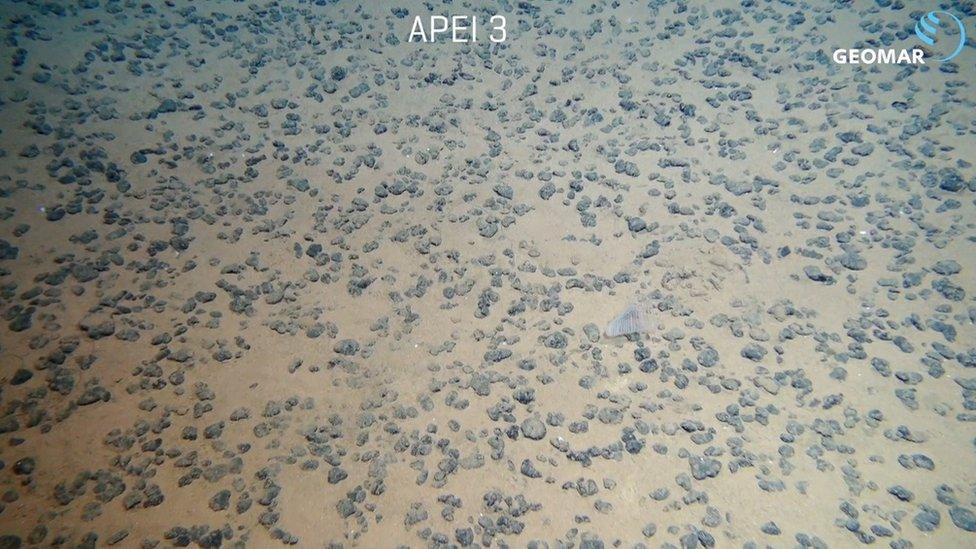

The concept, first envisaged in the 1960s, is to extract billions of potato-sized rocks called nodules from the abyssal plains of the oceans several miles deep.

Rich in valuable minerals, these nodules have long been prized as the source of a new kind of gold rush that could supply the global economy for centuries.

Interest in them has intensified because many contain cobalt and other metals needed for the countless batteries that will power the electric vehicles of a zero-carbon economy.

The process has been likened to "potato harvesting" on the sea bed

Dozens of ventures, most of them government-backed, have been exploring vast areas of the Pacific and Indian Oceans to assess their viability for mining.

And several companies have developed prototypes of "nodule collectors", giant robotic machines that would drive over the seabed, gathering the rocks and piping them up to ships at the surface.

We witnessed one of these devices - called Apollo II - being tested in the waters off southern Spain in 2019.

What's the problem?

Claudia Becker, a senior BMW expert in sustainable supply chains, tells me what led the car giant to decide against using deep sea metals.

"It's the fear that everything we do down there could have irreversible consequences," she said.

"Those nodules grew over millions of years and if we take them out now, we don't understand how many species depend on them - what does this mean for the beginning of our food chain?

"There's way too little evidence, the research is just starting, it's too big a risk."

The BBC's David Shukman explains how deep sea mining works

It's that lack of detailed research, which only began in earnest in recent years, that convinced BMW to support campaign group WWF, which is leading the push for a moratorium until more is understood.

Ms Becker says that mines on land, although plagued by allegations of child labour, deforestation and pollution, can at least be inspected and held to high standards.

"With those mines we do understand the consequences and we do have solutions but in the deep ocean we don't even have the tools to assess them."

She believes that deep sea mines can be avoided by turning to alternative, less damaging metals, designing batteries that require fewer minerals in the first place and developing a circular economy with far better recycling.

What do the mining companies say?

DeepGreen, which is planning to mine nodules in the Pacific, did not respond to my request for comment but released a statement saying the car companies were being 'irresponsible' in their claims.

"Where exactly will BMW get the battery metals it needs to fully electrify its products, and with what impact to our climate?

The Apollo II is lowered into the water off the coast of Malaga

"Will Volvo customers really prefer rainforest metals in their EVs once they realise their dire impacts on freshwater ecosystems, indigenous peoples, charismatic megafauna and carbon-storing forests?"

UK Seabed Resources, a subsidiary of US aerospace giant Lockheed Martin, with two licences to explore for minerals in the Pacific, said it was gathering the data needed to assess the "environmental soundness" of nodules.

Chris Williams, the company's managing director, said: "We are committed to a sustainable environment and that is why we are focused on establishing an environmental baseline."

A programme of intensive research is planned for coming years and, before any mining actually starts, there'll have to be impact assessments and political approval by the UN body in charge, the International Seabed Authority.

How serious are the risks?

Prof Rachel Mills, a specialist in deep sea chemistry at the University of Southampton, has gone through a dramatic change of mind about deep sea mining.

When I interviewed her nearly a decade ago, she thought ocean mines would be less damaging than mines on land but she now worries about the effect of huge plumes of sediment stirred up by the machines.

"I had a simplistic understanding of the ocean floor when you first asked me and I now realise that this level of disruption to the fragile aquatic environment could lead to an enormous level of impact."

She supports the call for a moratorium until more research is carried out into the organisms that live on the nodules and the role they play, and she's delighted by the move by BMW and the other companies.

"It's really significant, they're big names but I think they're riding a tide…I think a lot of people would say 'don't mess with the deep ocean'," she said.

Do all scientists agree?

Not at all - there's a spectrum of views in what's becoming an increasingly polarised debate.

Prof Bram Murton, a marine geologist and colleague of Prof Mills at the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton, says he's "horrified" at the approach of BMW and others.

He believes that deep sea mining can provide the raw materials for the zero-carbon transition and that it would be better for the companies to explore how to minimise the impacts.

"What they are doing instead is pretending the current status quo is sustainable, sufficient and acceptable. Which it isn't. And we will fail to meet our net-zero targets," he said.

And Dr Henko de Stigter, of the Dutch marine research organisation NIOZ, also questions whether the damage will be as extensive as campaigners claim.

He says that even if 10 mining contractors strip 200 sq km of seabed per year, and the sediment plumes spread over a total of 20,000 sq km, that's still only 0.006% of the ocean floor.

"To me that sounds different to the statement by WWF that deep seabed mining would affect areas on a continental scale and affect the vast ocean habitat in its entirety," he said.

What's next?

The intervention of the four big companies has added new fuel to the fire of this controversy.

According to one industry source, "it doesn't spell the end of seabed mining, instead it reinforces the need for more research to answer the key questions."

Meanwhile, WWF says more firms have been in touch about joining its campaign and it expects more to sign up in the coming months.

Jessica Battle, from WWF, told me: "We're hoping that this is the little snowball, if you wish, that is going to lead to an avalanche of responsible companies," sending a signal to governments and investors.

Follow David on Twitter., external