Boeing delays rerun of Starliner space capsule test

- Published

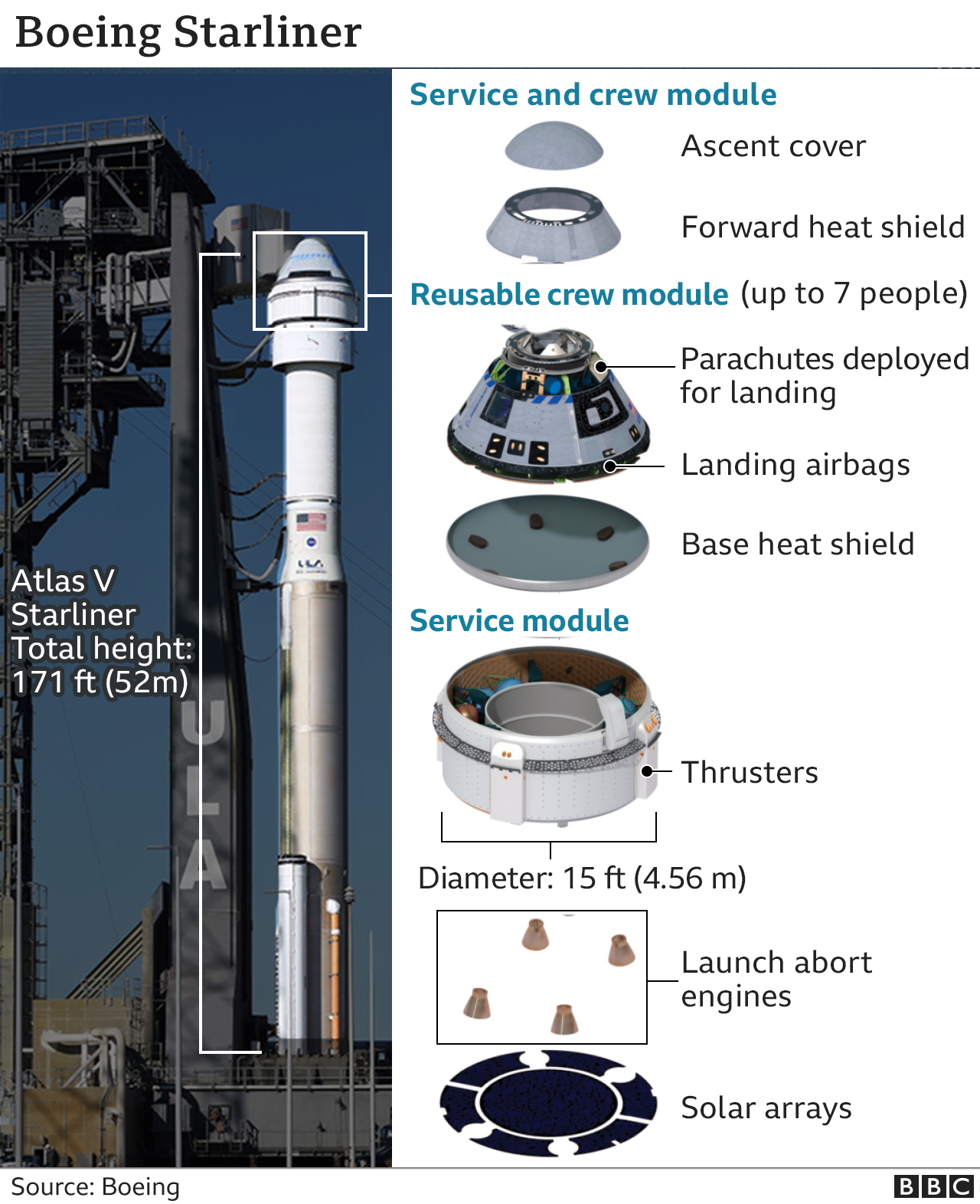

The Starliner stands ready atop its United Launch Alliance Atlas rocket

Boeing says it is checking the propulsion system valves on its CST-100 Starliner spacecraft, after Tuesday's planned launch was postponed.

The CST-100 Starliner will launch from Florida at some point to showcase how it can ferry crews to and from the International Space Station (ISS).

It will be the second test flight, and conducted with no people aboard.

The previous demonstration in 2019 encountered software problems that very nearly caused the loss of the capsule.

The Starliner will ride to orbit on an Atlas-5 rocket from the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida.

Controllers had been targeting Tuesday for the launch but scrubbed the countdown with two-and-a-half hours left on the clock, to allow for investigation of technical issues related to the capsule's propulsion system.

Now Boeing says a rescheduled launch on Wednesday will not happen either, external, because it needs more time to discover the reason for "unexpected valve position indications in the propulsion system".

Fortunately, the 2019 test Starliner still managed to land safely

It's just over 10 years since Boeing first presented its design for the CST-100 Starliner at the Farnborough Air Show in the UK.

It was a response to the call for commercial companies to take over the responsibility for low-Earth orbit crew transportation, post the soon-to-retire space shuttles.

The US space agency (Nasa) gave technical and financial support to both Boeing and the SpaceX company, to help them develop new capsules. The idea was that the vehicles would then be engaged on a commercial basis whenever Nasa needed astronauts sent up to the ISS.

But while SpaceX is now two crewed operational flights into this privatised era, Boeing has yet to run a single crewed mission in a Starliner. And that's because Boeing's first unpiloted "Orbital Flight Test" in December 2019 went seriously awry.

The problems started with a clock error on the capsule just after launch that made the vehicle think it was in a different flight phase than was really the case.

This prompted the onboard computer system to over-fire Starliner's thrusters and burn so much fuel it became impossible to reach the intended destination of a docking with the space station. Controllers on the ground could see the problem playing out but had difficulty communicating with the spacecraft.

After the truncated mission, it also emerged that poorly designed software could have resulted in the capsule colliding with its aft service section when the two were commanded to separate just prior to re-entry into the Earth's atmosphere. Fortunately, this issue was caught and prevented, and the capsule landed safely in the New Mexico desert.

The post-mission review initiated a series of re-designs and upgrades that have enabled Boeing to attempt an Orbital Flight Test 2 (OFT-2).

The only "individual" aboard will be "Rosie the Rocketeer"

Chris Ferguson, a former Nasa astronaut and Boeing's director of Starliner mission operations, said the company had run full-mission duration simulations of the new software on the capsule.

The new code, he added, had implemented every correction recommended by the review.

"We fixed every one, we addressed every one. We want this next flight to be as clean as it could possibly be," he told reporters.

"We have thoroughly dug into, tested and verified hundreds of times the software code, to ensure that it performs exactly the way we intend on OFT-2."

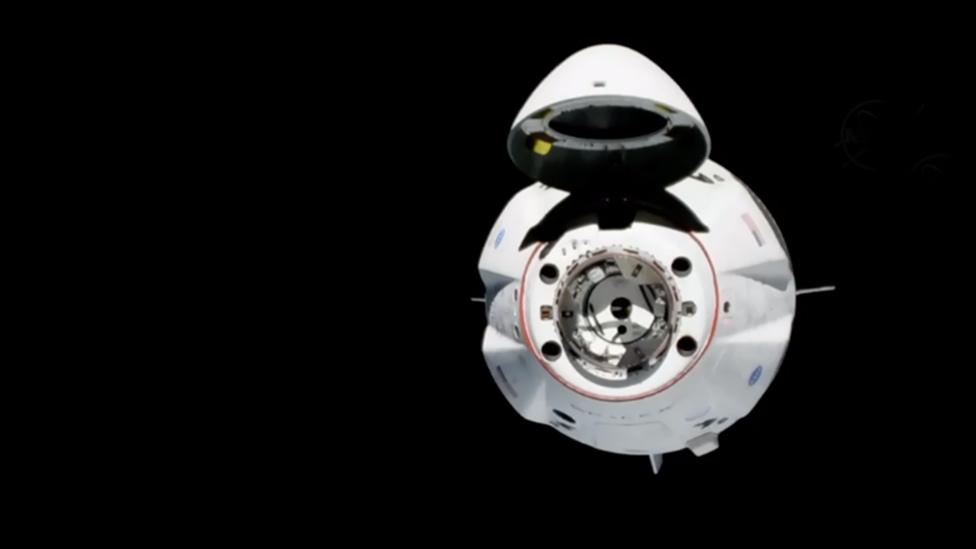

The SpaceX Dragon capsule is already flying crews to the ISS

The re-run will follow the same profile: an uncrewed mission to the ISS. That said, an anthropomorphic test device, more commonly known as a flight dummy, dubbed "Rosie the Rocketeer", will once again strap in for the ride.

Rosie and "her" capsule will stay attached to the station for five days, before departing for a parachute-assisted descent and landing at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico.

If Boeing can put the flaws of OFT-1 behind it, Nasa could clear Starliner to start carrying people before the end of the year.

This would finally give the agency the two new crew-transportation systems it sought when the shuttles were retired, external to museums exactly 10 years ago.

"This is a huge component to returning this launch capability from the United States and having redundancy between SpaceX and Boeing, so that we're not reliant on just one company to get astronauts to the International Space Station," said Nicole Mann, a Nasa astronaut who has been selected to fly on the first crewed Starliner mission.

And this capability would also open up space to wider participation, she believed: "You're going to see more folks in low-Earth orbit who are not Nasa astronauts. That's great. I think for the younger generation, they're going to see scientists, engineers and maybe journalists in space, and they're going to be able to capture the amazement of space and share the experience."