Nature: Rattlesnakes' sound 'trick' fools human ears

- Published

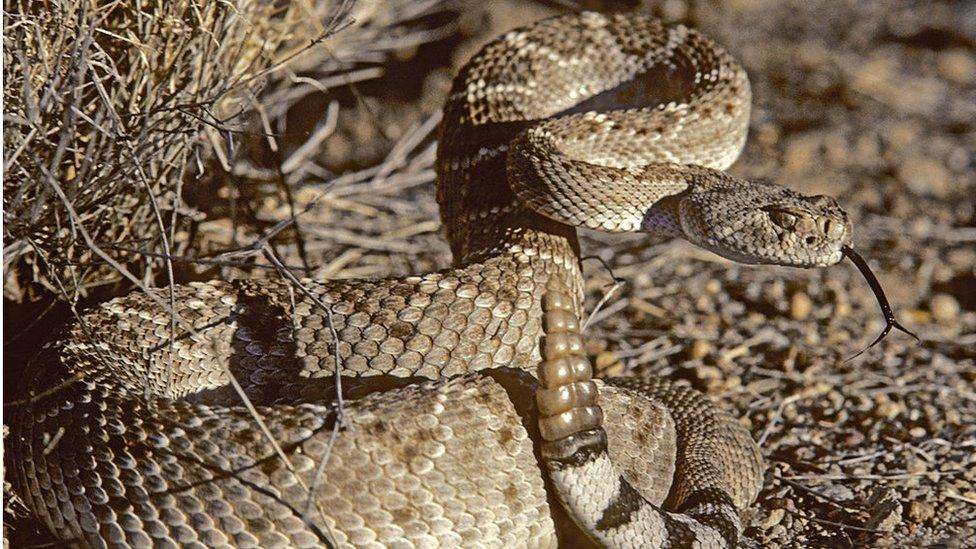

Rattlesnakes are the source of the majority of bites inflicted on humans in the US every year

Rattlesnakes have evolved a clever method of convincing humans that danger is closer than they think, say scientists.

The sounds of their shaking tail get louder as a person approaches, but then suddenly switches to a much higher frequency.

In tests, the rapid change in sound made participants believe the snake was much nearer than it was in reality.

The researchers say the trait evolved to help snakes avoid being trampled on.

The sibilant sound of the rattlesnake's tail has long been a movie cliché.

The tell tale rattle is made by the rapid shaking together of hard rings of keratin at the tip of the reptiles' tails.

Keratin is same protein that makes up our fingernails and hair.

The hard keratin segments make up the rattle on the snake's tail

The key to the noise is the snake's ability to shake its tail muscles up to 90 times a second.

This vigorous shaking is used to warn other animals and humans of their presence.

Despite this, rattlesnakes are still responsible for the majority of the 8,000 or so bites inflicted on people in the US every year.

Researchers have known for decades that the rattling can change in frequency but there's been little research about the significance of the shift in sound.

In this study, scientists experimented by moving a human-like torso closer to a western diamondback rattlesnake and recording the response.

As the object got closer to the snake, the rattles increased in frequency up to around 40Hz. This was followed by a sudden leap in sound into a higher frequency range between 60-100Hz.

To figure out what the sudden change meant, the researchers carried out further work with human participants and a virtual snake.

The increasing rattling rate was perceived by participants as increasing loudness as they moved closer.

Hunters in Texas with a captured western diamondback rattlesnake

The scientists found that when the sudden change in frequency occurred at a distance of 4 metres, the people in the test believed it was far closer, around one metre away.

The authors believe the switch in sound is not just a simple warning, but an intricate, interspecies communication signal.

"The sudden switch to the high-frequency mode acts as a smart signal fooling the listener about its actual distance to the sound source," says senior author Boris Chagnaud from Karl-Franzens-University in Graz, Austria.

"The misinterpretation of distance by the listener creates a distance safety margin."

The authors believe that the snakes behaviour takes advantage of the human auditory system, which has evolved to interpret an increase in loudness as something that is moving faster and getting closer

"Evolution is a random process, and what we might interpret from today's perspective as elegant design is in fact the outcome of thousands of trials of snakes encountering large mammals," said Dr Chagnaud.

"The snake rattling co-evolved with mammalian auditory perception by trial and error, leaving those snakes that were best able to avoid being stepped on."

The study has been published, external in the journal Current Biology.

Follow Matt on Twitter @mattmcgrathbbc, external.