BepiColombo: Europe's mission to Mercury returns first pictures

- Published

"Happy snaps": The first images of Mercury have delighted mission scientists

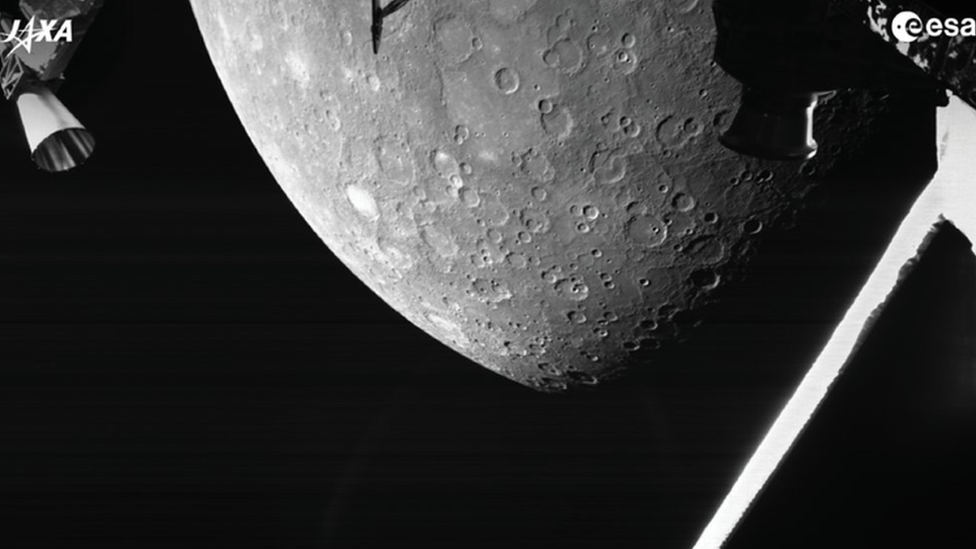

Europe's BepiColombo mission has returned its first pictures of Mercury, the Solar System's innermost planet.

The probe took the images shortly after it zipped over the little world at an altitude of just 200km (125 miles).

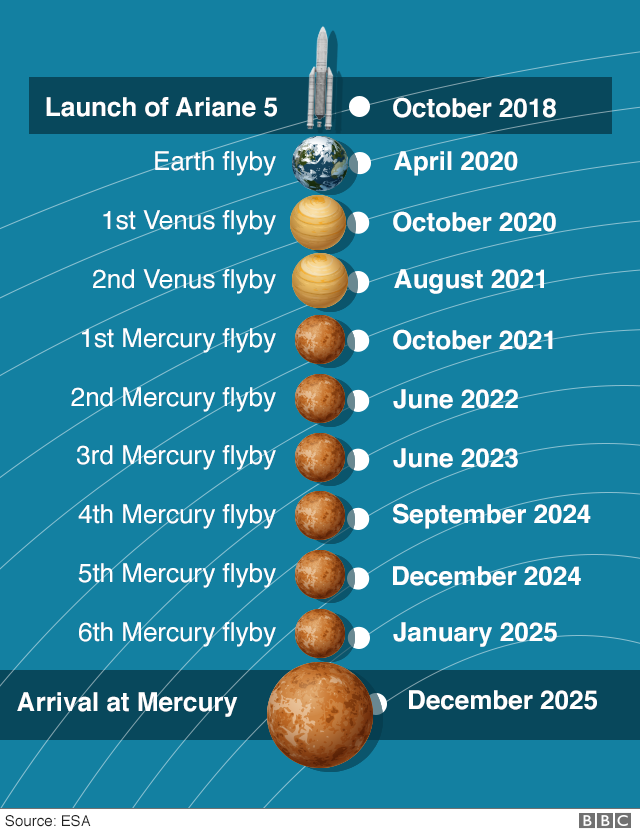

Controllers have planned a further five such flybys, each time using the gravitational tug of Mercury to help control the speed of the spacecraft.

The aim is for Bepi to be moving slow enough that eventually it can take up a stable orbit around the planet.

This should happen by the end of 2025.

Bepi took the pictures as it moved away from the planet

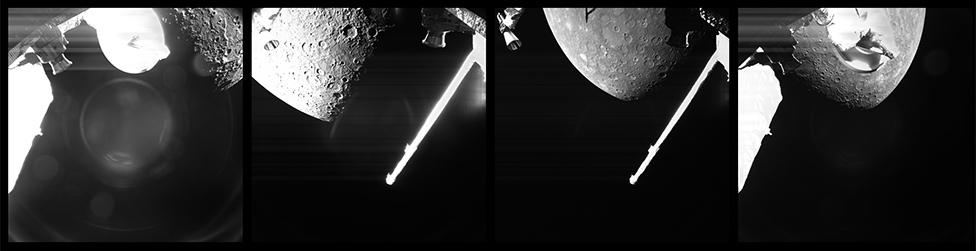

The mission's first pictures of Mercury were snapped by low-resolution monitoring cameras on the side of the probe. For the moment, these are all that are available.

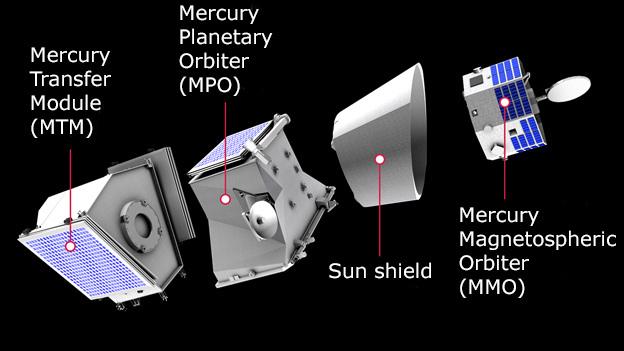

Bepi is not ready to deploy its high-resolution science cameras. They are tucked away inside what is referred to as the spacecraft stack.

Bepi is essentially two spacecraft in one. One part has been developed by the European Space Agency (Esa), the other part by the Japanese space agency (Jaxa). The way these two components have been packed for the journey to Mercury obstructs the apertures of the main cameras.

BepiColombo: Mission to uncover mysteries of Mercury

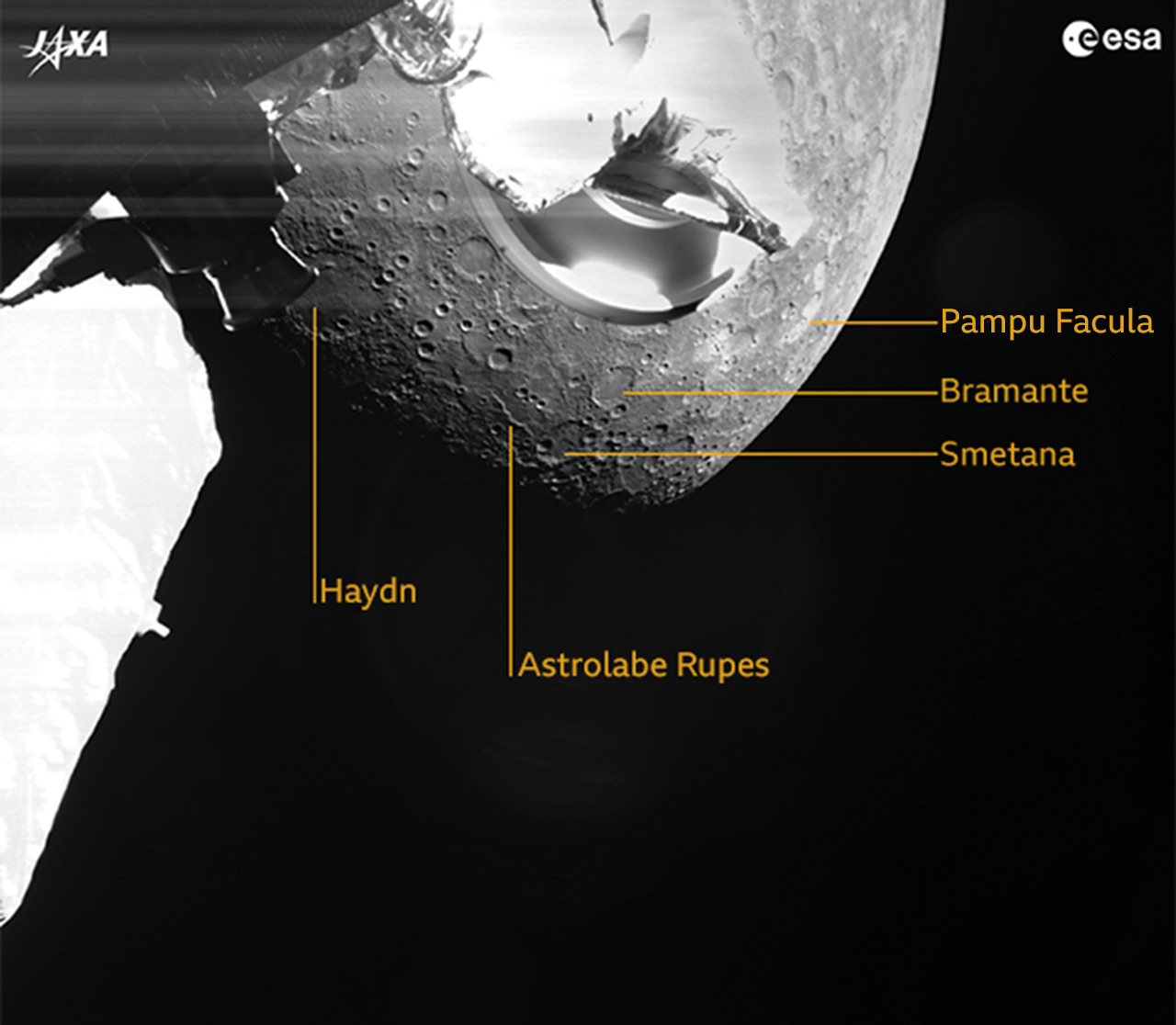

The low-resolution cameras were certainly good enough to identify well-known features

The engineering, or "selfie", cameras were still good enough to pick out recognisable features on the planet's surface.

The simple black-and-white photos started filtering back to Earth on Saturday. Once all are processed, Esa is expected to run them together to make a short film, most probably for release on Monday.

Prof Dave Rothery from the UK's Open University declared himself delighted with what Bepi had seen.

"It's just happy snaps as we're whizzing by, but what a wonderful view we've had of the planet," he told BBC News.

"You're seeing a cratered surface, but also areas which have been smoothed by vast outpourings of volcanic lava. Some of the brighter areas are where there've been volcanic explosions in the distant past, and you can also see where today some of the surface material is dissipating to space.

"When we see really high-resolution images when we're in orbit, you'll see that the top 10-20m of the surface is dissipating to space, giving you these steep-sided, flat-bottomed depressions that we call hollows."

Although Bepi is a long way from beginning proper science operations, quite a few of the probe's instruments were switched on for the flyby. Phenomena such as magnetic fields and some particles can still be sensed, even in the stack configuration.

"We'll get data back," Dr Suzie Imber, from Leicester University, UK, said, "but the purpose of the flyby, and the six flybys in total at Mercury, is to help us change our trajectory and slow us down.

"Eventually, in a few years from now in December 2025, our spacecraft and Mercury will be in the same place going in the same direction. And so, finally, we can separate our spacecraft, and get into orbit."

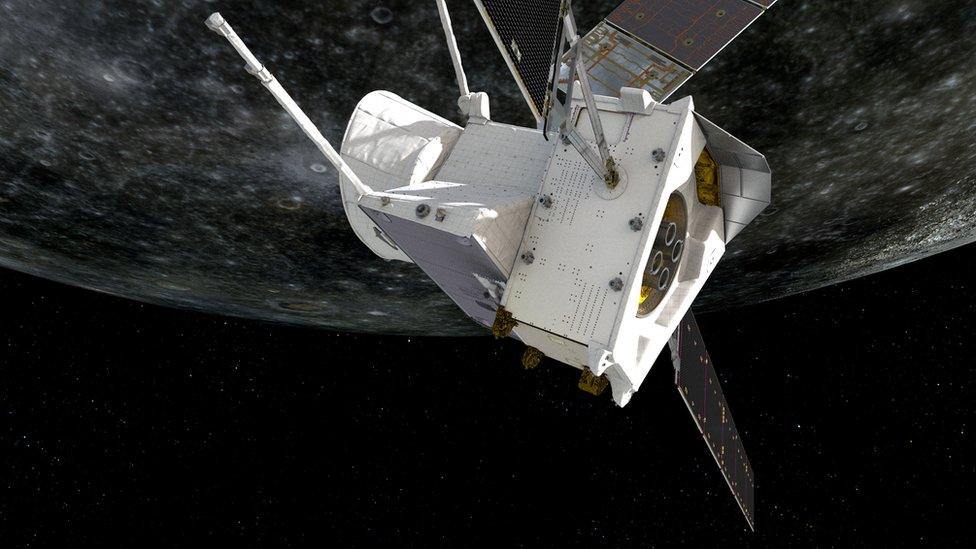

Artwork: Bepi has five further flybys planned to get itself into orbit

This first flyby will have put Bepi in a two-to-three resonance with Mercury. That's to say, as Mercury goes three times around the Sun, Bepi will go around twice.

The next flyby in June next year, will slow this to a three-to-four resonance: Bepi will circle the Sun three times compared with Mercury's four circuits.

Further passes in June 2023, September 2024, December 2024, and January 2025 should see Bepi in a regular orbit to begin full science operations in 2026.

The European and Japanese components travel to Mercury as a stack

What science will BepiColombo do at Mercury?

The European and Japanese elements of the mission will separate when they get into orbit at Mercury and perform different roles.

Europe's Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) is designed to map Mercury's terrain, generate height profiles, collect data on the planet's surface structure and composition, as well as sensing its interior.

Japan's Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (MMO) will make as its priority the study of Mercury's magnetic field. It will investigate the field's behaviour and its interaction with the "solar wind", the billowing mass of particles that stream away from the Sun. This wind interacts with Mercury's super-tenuous atmosphere, whipping atoms into a tail that reaches far into space.

It's hoped the satellites' parallel observations can finally resolve the many puzzles about the hot little world.

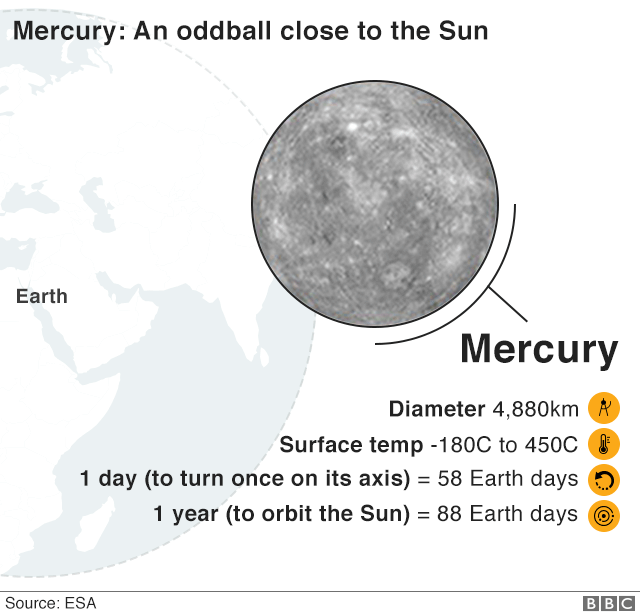

One of the key ones concerns the object's oversized iron core, which represents 60% of Mercury's mass. Science cannot yet explain why the planet only has a thin veneer of rocks.

"When we get into orbit, we'll then start studying the magnetic field at Mercury, and the surface of Mercury, which has huge temperatures of 450C, the temperature of a pizza oven, and yet it has water on the surface in some places," said Prof Mark McCaughrean, Esa's senior advisor for science and exploration.

"Bepi is only the third mission ever to go to Mercury and will be much closer in for much longer than the previous missions. So, we've got a real chance of answering some of those mysteries about why the planet is the way it is," he told BBC News.

Europe's MPO was largely assembled in the UK by Airbus.