Climate change: Carbon emissions show rapid rebound after Covid dip

- Published

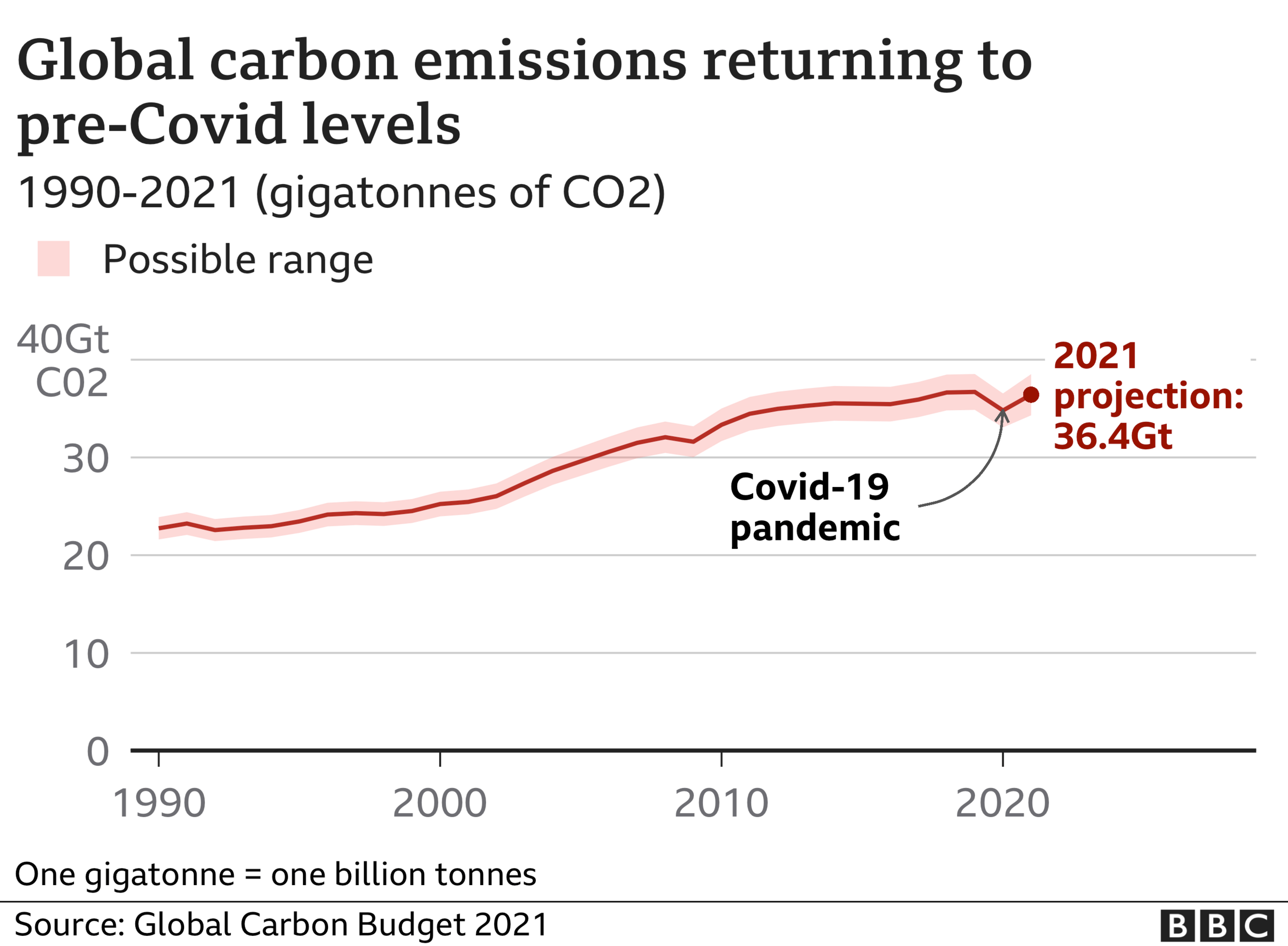

Global carbon dioxide emissions are set to rebound to near the levels they were at before Covid, in a finding that has surprised scientists.

The amount of planet-heating gas released in 2020 fell by 5.4% as the pandemic forced countries to lock down.

But a scientific report by the Global Carbon Project predicts CO2 emissions will rise by 4.9% this year.

It shows the window is closing on our ability to limit temperature rise to the critical threshold of 1.5C.

This rise in carbon dioxide (CO2) released into the atmosphere underlines the urgency of action at summits like COP26 in Glasgow, scientists say.

Important deals have been struck at the meeting this week, on limiting emissions of methane and on curbing deforestation.

Yet emissions from coal and gas are predicted to grow more in 2021 than they fell the previous year - though carbon released from oil use is expected to remain below 2019 levels.

Dr Glen Peters, from the Center for International Climate Research (Cicero) in Oslo, Norway, said: "What many of us were thinking in 2020 - including me - was more of a recovery spread out over a few years, as opposed to a big hitch in 2021.

"That's where the surprise comes for me - that it happened so quick, and also there's a concern that there's still some recovery to come."

This rapid rebound in emissions is at odds with the ambitious CO2 cuts required in order to limit global temperature rise to 1.5C. This is the increase viewed by scientists as the gateway to dangerous levels of global warming.

The 16th annual Global Carbon Budget report was compiled by more than 94 authors who analysed economic data and information on emissions from land activities, such as forestry.

Climate Basics: CO2 explained

It shows that, if we continue along as we are and don't cut emissions, there's a 50% likelihood of reaching the 1.5C of warming in about 11 years. This concurs with the findings in a recent UN report that suggested we would get there by the early 2030s., external

Prof Corinne Le Quéré, from the University of East Anglia, said: "To limit climate change to 1.5C, emissions of CO2 need to reach net zero by 2050. Doing this in a straight line would mean cutting global emissions down by 1.4 billion tonnes of CO2 each year."

The fall in 2020 was 1.9 billion tonnes, but that was in the lockdown.

So reducing emissions by an amount roughly equivalent to that in the post-lockdown period presents a daunting challenge. But the scientists stress that it remains achievable.

COP26 climate summit - The basics

Climate change is one of the world's most pressing problems. Governments must promise more ambitious cuts in warming gases if we are to prevent greater global temperature rises.

The summit in Glasgow is where change could happen. You need to watch for the promises made by the world's biggest polluters, like the US and China, and whether poorer countries are getting the support they need.

All our lives will change. Decisions made here could impact our jobs, how we heat our homes, what we eat and how we travel.

"Personally, I think [the 1.5C goal] is still alive, but the longer we wait, the harder it will get... we need immediate action and reductions," said co-author Pierre Friedlingstein, from the University of Exeter.

Prof Le Quéré concurred: "This decrease of 1.4 billion tonnes each year is a decrease that is very large indeed, but is feasible with concerted action. We need to limit climate change as low as possible and 1.5C is a good target to maintain."

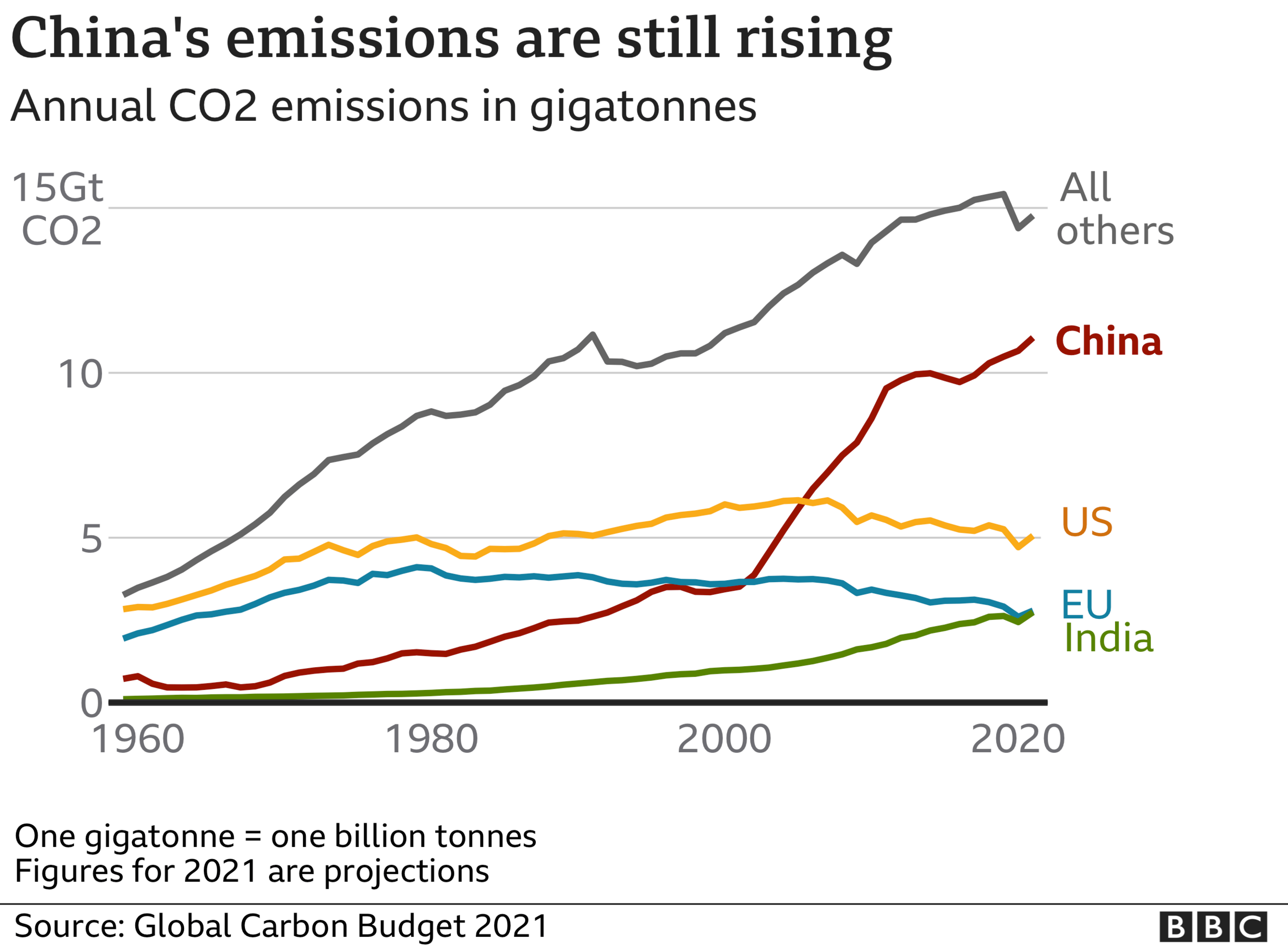

Emissions in China are expected to be 5.5% higher in 2021 than in 2019 and are also projected to rise in India, with a 4.4% increase in 2021 relative to the pre-pandemic level.

Dr Peters said commentators should remember that, while China is responsible for nearly 30% of global carbon emissions, that left another 70% for the rest of the world to tackle.

The superpower has also demonstrated weaker economic growth in the past decade and has been switching to low-carbon energy sources at a faster rate than many other countries.

Its emissions growth this year is related to stimulus packages - focused on heavy industry - which are in turn a response to the Covid-related slowdown.

Both India and China have plenty of installed renewables capacity. Here, workers clean solar panels in Gujarat, India

"China is doing very well on many dimensions: it's deploying solar, it's deploying wind, electric buses, electric vehicles, and so there's lots of positive things going on in China," Dr Peters explained. "But unfortunately, the stimulus packages often tend to focus on industrial sectors - construction, steel, cement. This requires coal.

"If China can turn that around, it has plenty of potential to reduce emissions because it has so much potential for large-scale deployment of solar and wind [power] that other countries don't have."

At COP26 this week, India pledged to reach net zero - where its emissions are reduced and any remaining ones balanced out by projects such as tree planting - by 2070. Like China, it has installed lots of wind and solar capacity, but fossil fuel sources have also been growing.

Projected 2021 emissions in the US, European Union and the rest of the world remain, respectively, 3.7%, 4.2%, and 4.2% below their 2019 levels - in large part due to policies designed to reduce emissions from fossil fuels.

Follow Paul on Twitter., external