COP26: Coal compromise as leaders near climate deal

- Published

- comments

A draft agreement at the COP26 climate summit has watered down commitments to end the use of coal and other fossil fuels, as countries race to reach a deal after two weeks of talks.

While the language around fossil fuels has been softened, the inclusion of the commitment in a final deal would be seen as a landmark moment.

A deal must be agreed by the end of the summit, which is in its final hours.

The UN meeting is seen as crucial for limiting the effects of global warming.

The draft agreement, which was published early on Friday following all-night talks, also asks for much tighter deadlines for governments to reveal their plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

And it also strengthens support for poorer countries fighting climate change.

Negotiations over a final deal could stretch late into Friday, or potentially even longer.

"This text is the bare minimum. The next few hours are going to determine the new dawn," says Simon Stiell, climate resilience minister for Grenada, a small island that is highly vulnerable to climate change.

"If the text withstands the battering it may get, we are holding onto 1.5C by our fingernails," he says, referring to the ambition to limit global temperature rise to 1.5C degrees to avoid the worst effects of climate change.

Negotiators from countries that depend on fossil fuels may still attempt to amend the text before the summit ends.

Climate groups cautiously welcomed signs of progress in the draft but said there is a long way to go yet.

"The key line on phasing out coal and fossil fuel subsidies has been critically weakened, but it's still there and needs to be strengthened again before this summit closes," says Jennifer Morgan of Greenpeace International.

"But there's wording in here worth holding on to and the UK presidency needs to fight tooth and nail to keep the most ambitious elements in the deal," she says.

Prof Jim Watson at University College London said the draft agreement had encouraging elements, but that overall it was "nowhere near ambitious enough".

The draft comes after UN chief António Guterres warned that COP26 would probably not achieve its aims and the crucial goal of limiting global warming to 1.5C is on "life support".

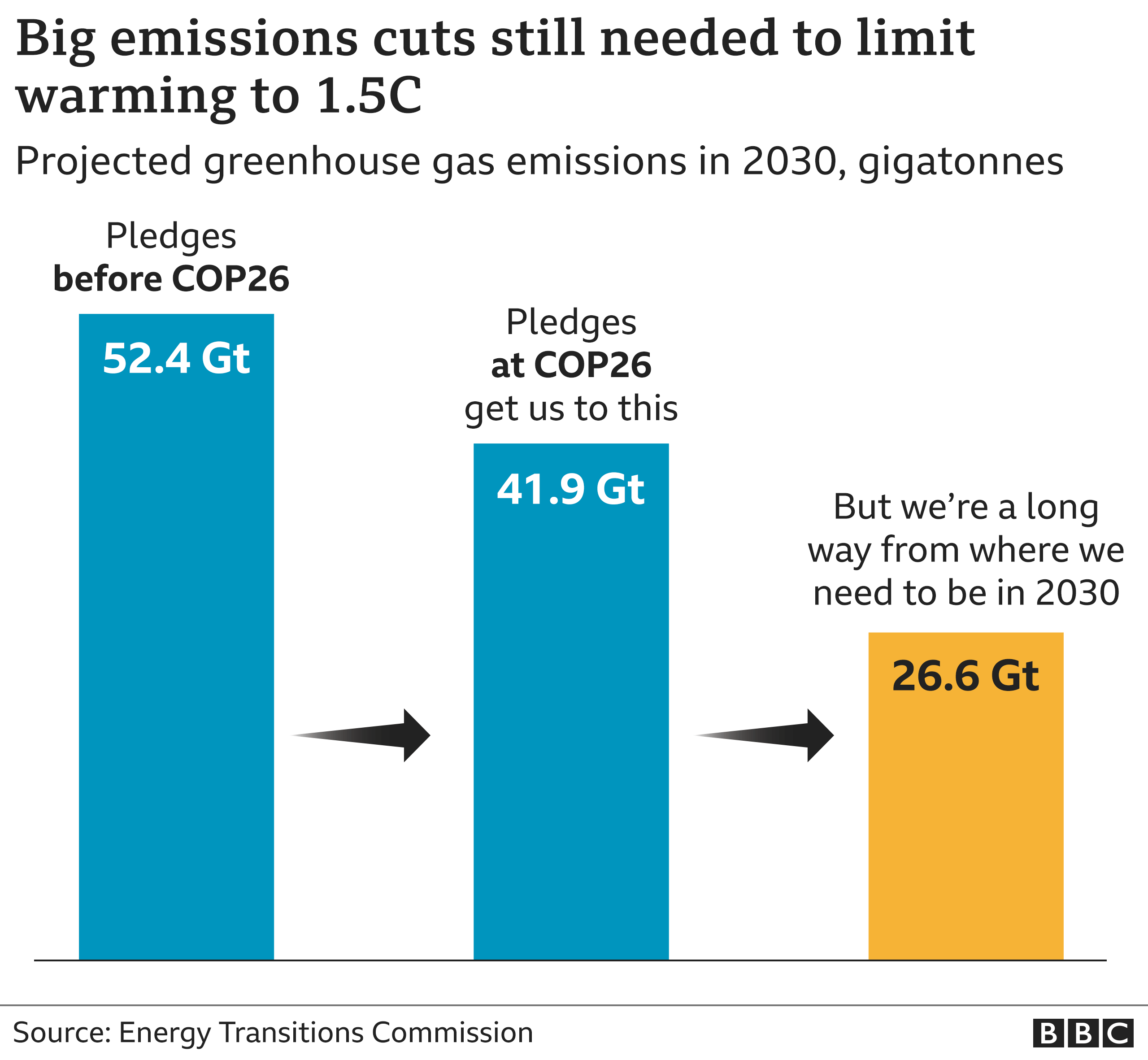

Limiting warming to 1.5C compared to pre-industrial levels is a key part of the Paris agreement that most countries signed up to. It requires cutting global emissions by 45% by 2030 and to zero overall by 2050.

One example of the impact of global temperature rise above 2C is the death of virtually all coral reefs, scientists say.

A previous version of the agreement called upon parties to "accelerate the phasing-out of coal and subsidies for fossil fuels".

This has been changed to call for "accelerating the phaseout of unabated coal power and of inefficient subsidies for fossil fuels".

Unabated coal is coal produced without the use of technology to capture the emitted carbon.

But the draft requests that countries submit their plans - known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs) - to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to climate change by next year's climate summit. Previous agreements asked countries to submit these NDCs every five years.

This latest draft of the decision has gained in strength in many areas - but as in every negotiation, there are some losses too.

One small but important change is in relation to 1.5C - the text formerly said that the world should aim to keep global temperatures under this threshold "by 2100".

Some scientists for the IPCC [the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] saw this as allowing temperatures to go well beyond 1.5 as long as they were brought back down by the end of the century. This has been changed to simply say "limiting temperatures to 1.5C."

The commitment of countries to come back next year with a new carbon-cutting plan is still in the draft, although the language around it has been softened.

Perhaps of greater concern though is the inclusion of the phrase "taking into account different national circumstances".

While this is being seen as a way of allowing vulnerable states and other low-emitting countries to avoid having to update their plans, could it also be used by China to do the same thing?

Where the new document really gains strength is in relation to finance and loss and damage, two key issues for developing nations.

Money for adapting to the worst impacts of climate change will be doubled, and the baseline year will be 2021.

This is a first step on a road that will please the most vulnerable nations.

A key sticking point at COP26 is climate finance - the money promised by richer countries to poorer countries to fight climate change. It is controversial because developed countries are responsible for most greenhouse gas emissions, but developing countries see the worst effects of climate change.

Despite the promises made at COP26 so far, the planet is still heading for 2.4C of warming above pre-industrial levels, according to a report by Climate Action Tracker.

Watch: Climate activists from the Philippines, the UK and Argentina take questions on climate change

What has been agreed at COP26?

A series of agreements between groups of countries have been announced so far:

In a surprise announcement, the US and China agreed to work together this decade to limit global temperature rise to 1.5C

More than 100 world leaders promised to end and reverse deforestation by 2030, including Brazil, home to the Amazon rainforest

The US and the EU announced a global partnership to cut emissions of the greenhouse gas methane by 2030 - reducing methane in the atmosphere seen as one of the best ways to quickly reduce global warming

More than 40 countries committed to move away from coal - but the world's biggest users like China and the US did not sign up

A new alliance that commits countries to setting a date to ending oil and gas use - and halting granting new licences for exploration - was launched

Related topics

- Published10 November 2021

- Published12 November 2021

- Published5 November 2021