COP26: Evasive words and coal compromise, but deal shows progress

- Published

Protesters near the COP conference, demonstrating in support of victims of oil exploration

While the Glasgow Climate Pact is an ambitious attempt to rein in rising temperatures, the last-minute row over coal has undoubtedly cast a shadow over the deal.

India was joined by China in pushing for a watering down of this key commitment, insisting on "phasing down" rather than "phasing out".

It was a brazen display of geo-political muscle that left developing countries and island states with little choice but to go along with the changes.

The new pact comes just a few days after another notable Chinese achievement.

Last Wednesday, the Xinhua news agency trumpeted, external the fact that the country produced more coal than ever before on a single day.

Some 12 million tonnes of the black stuff were mined. When consumed for energy, the one day of coal will produce carbon dioxide emissions roughly equivalent to Ireland's output for an entire year.

This is the carbon reality that's hitting our atmosphere every single day.

Seen in that light, the agreement reached here after extended negotiations looks like a limp sticking-plaster for the deep wound that's threatening life on this planet.

Negotiators who worked through the night to land the pact would undoubtedly disagree with that assessment.

The actual text of the final agreement is quite progressive, getting countries to come back again with strengthened plans next year.

It's also notable for naming coal as a root cause of the problem, for the first time in 30 years of UN diplomacy.

There's also a significant doubling of money to help poor countries adapt to the impacts of climate change - and the prospect of a trillion dollar a year fund from 2025, compared with the current goal of $100bn a year.

Observes also say there is the "start of a breakthrough" on the key question of loss and damage.

However, there are also some significant shortcomings in the agreement.

There are weaselly clauses that will allow some countries to avoid updating their plans to cut emissions, depending on "differing national circumstances".

There are real worries that some bigger developing economies like India and China will use that clause to skip updating their plans next year.

Members of the India and China delegations on the last day - in the final moments, the two countries pushed to water down the deal

For countries on the front lines, there is still too much focus on cutting carbon emissions at the expense of helping them adapt to a changing climate.

Some of the real-world pledges signed here were beyond a joke. South Korea was named as a country due to give up coal in the 2030s. But the government in Seoul sheepishly pointed to a clause in the pledge saying "2030s or as soon as possible thereafter" to say they'll stop burning in 2050.

In a similar vein, the launch here of a global effort to move away for petrol and diesel engines was a damp squib, with major car countries like Germany and the US not signing up.

There are compromises in any process involving 197 parties.

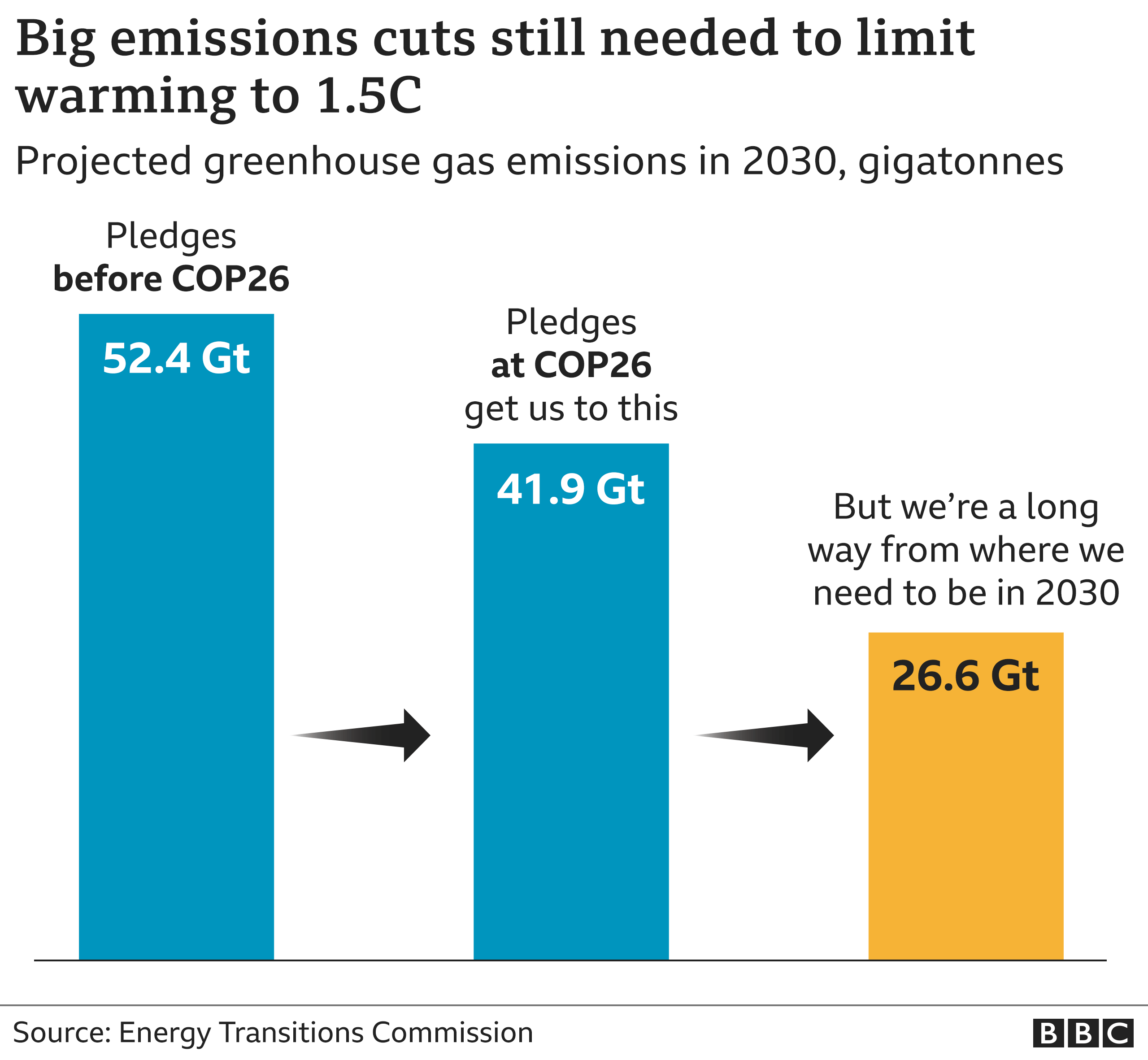

But does the overall package agreed here keep the world from warming by more than 1.5C, the long stated goal of COP26?

The agreement will help revive the sense of international collaboration that's been badly damaged in recent years by nationalist tendencies around the world.

And ultimately, this pact - flawed and late as it may be - does keep the flame of hope alive that temperatures may be held in check, somewhere between 1.8C and 2.4C this century.

But that's a frightening prospect in a world that's warmed by just over half that amount already, with massive impacts around the globe.

The sad reality, as with record Chinese coal production, is that the atmosphere only responds to emissions, and not decisions made in a conference like COP26.

Climate stripes visualisation courtesy of Prof Ed Hawkins and University of Reading.