James Webb Space Telescope given revised 24 December launch

- Published

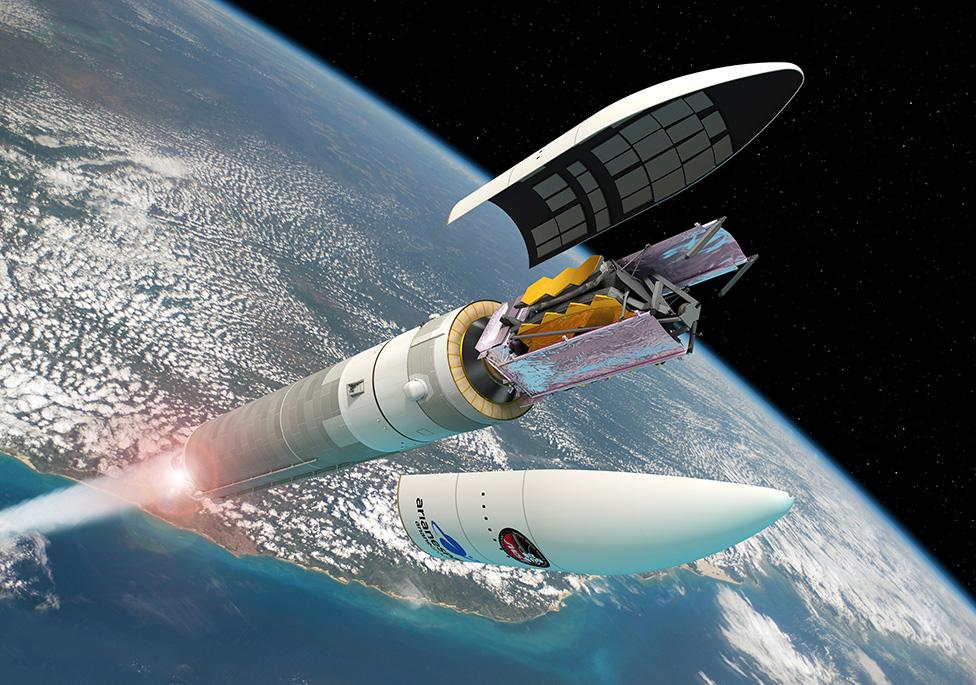

Watch engineers attach James Webb to its Ariane rocket

US and European officials have confirmed 24 December for the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

Engineers completed final checks on Friday before closing the observatory behind the nose cone of its Ariane rocket.

Everything is on track now for a lift-off from the Kourou spaceport in French Guiana next Friday at 09:20 local time (12:20 GMT).

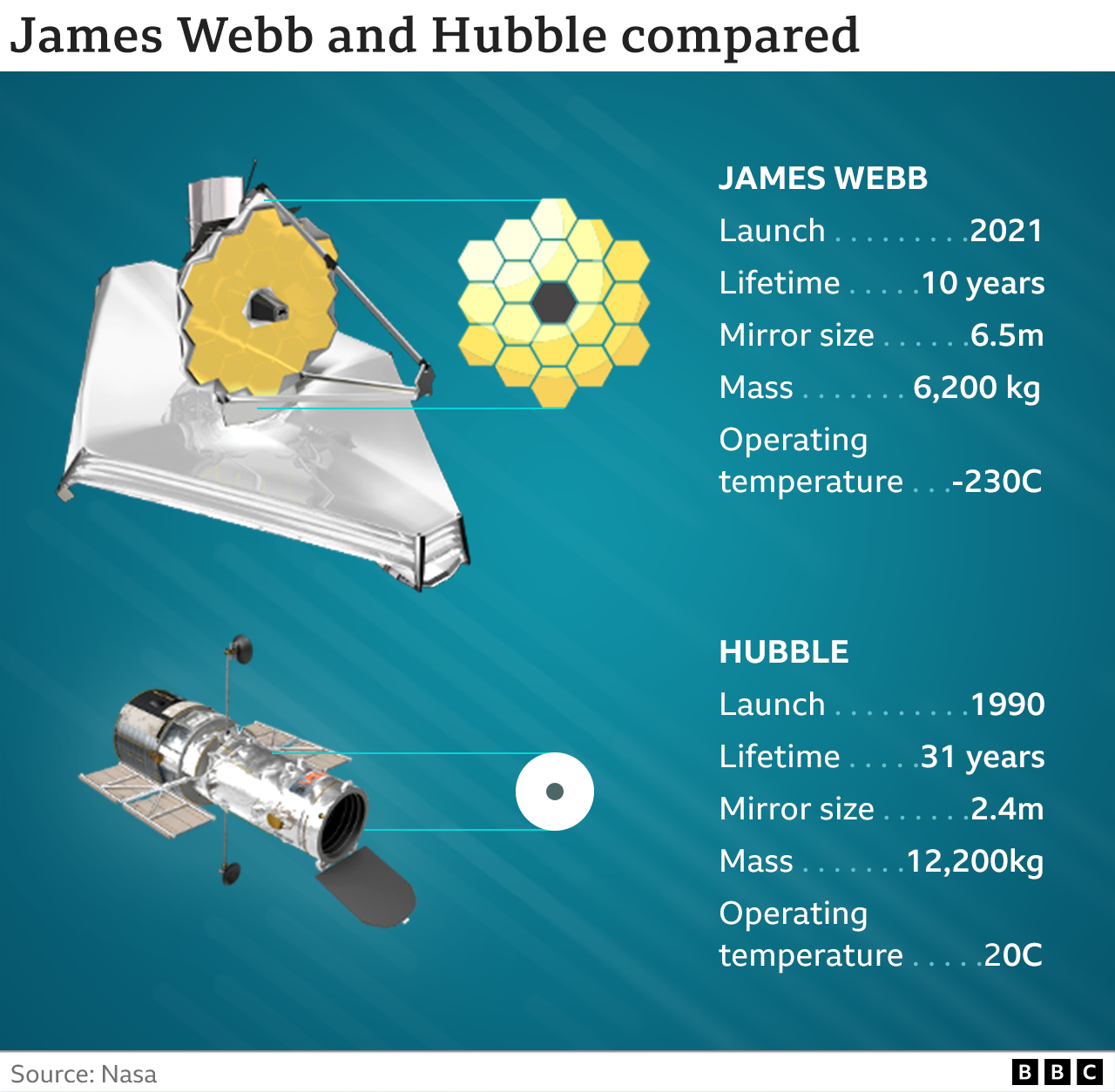

Webb is the $10bn (£7.6bn) successor to the Hubble Space Telescope.

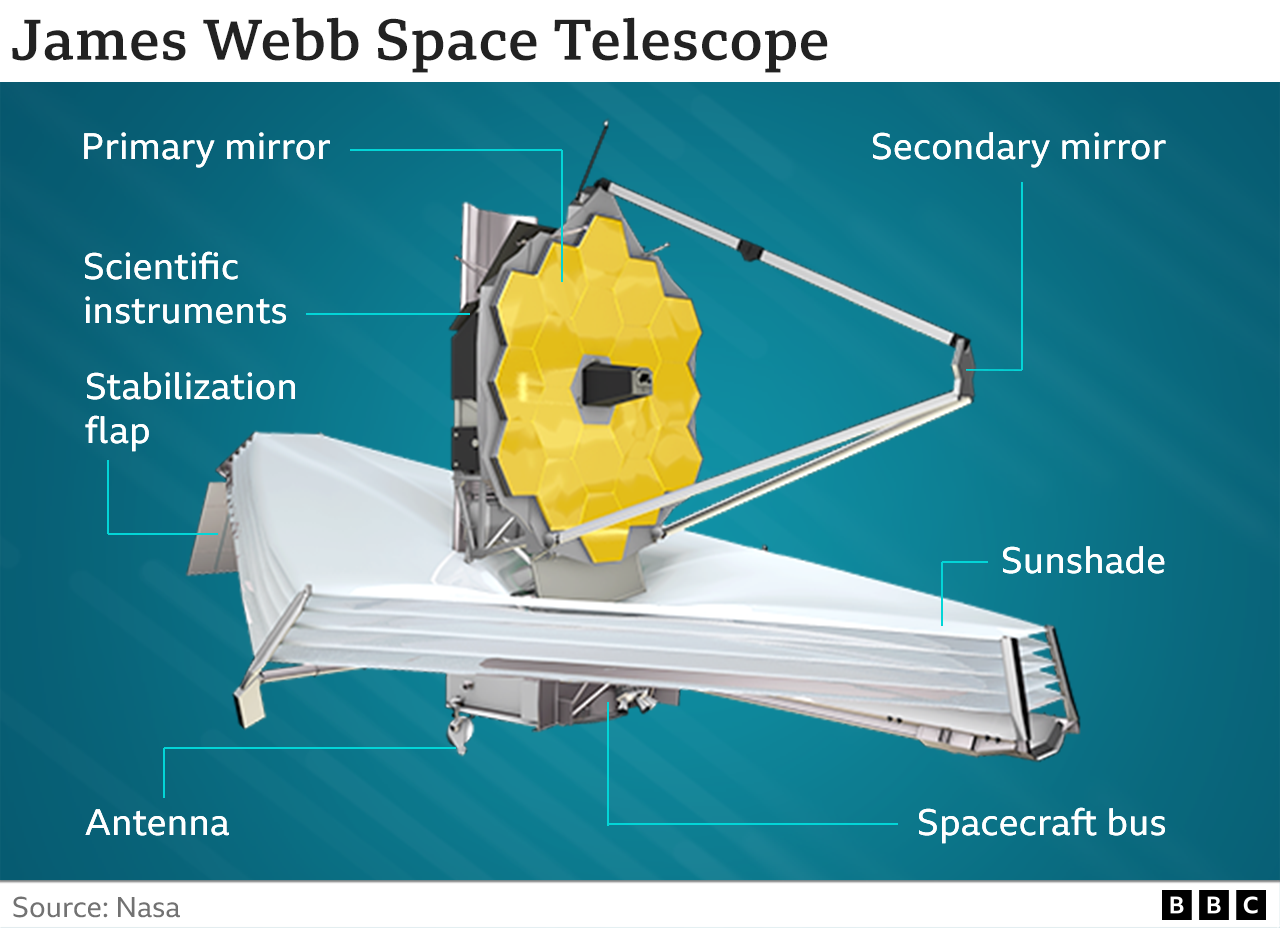

The new observatory has been designed to look deeper into the Universe than its predecessor and, as a consequence, detect events occurring further back in time - more than 13.5 billion years ago.

Scientists also expect to use its more advanced capabilities to study the atmospheres of distant planets in the hope that signs of life might be detected.

The US space agency Nasa, which leads the Webb project, and its partner the European Space Agency (Esa), released pictures on Saturday showing the moment of Webb's encapsulation.

The giant fairing that will protect the telescope as it climbs through the atmosphere was lowered into place with the aid of guide lasers.

The pictures are the last we will see of Webb and its golden mirrors on Earth. The next time we'll get a view of the observatory that has taken 30 years to design and build will be when it comes off the top of the rocket at the end of its 30-minute ascent.

This is how Kourou launch director Jean-Luc Voyer will call the countdown

A video camera has been installed on the Ariane to show the telescope moving away into the distance to begin its mission.

Engineers had put the launch on hold for a few days while they investigated a troublesome communications cable carrying data from Webb to ground-support equipment. Once this was fixed, the final "aliveness" tests on the telescope's subsystems could be run.

Artwork: The clamshell-shaped fairing will protect Webb as it climbs to space

Thomas Zurbuchen, Nasa's director of science, said the joint US-European team working on getting Webb ready would continue to be cautious right up to the moment of launch.

"We're not taking any risks with Webb," he told reporters on Thursday. "It's already risky enough the way it is. We're absolutely making sure that everything works."

Arianespace, the French company that manages operations in Kourou, will hold a launch readiness review on Tuesday. Assuming no issues come up, the Ariane vehicle, with Webb bolted on top, will then roll out to the pad.

The rocket will have a half-hour window in which to get off the ground on Friday.

Artwork: Webb will investigate the gases in the atmospheres of distant worlds

If bad weather or minor technical issues intervene, there are launch opportunities on 25 and 26 December, after which teams would have to stand down for a day to allow production of hydrogen and oxygen propellants at the spaceport to catch up.

"We reproduce the oxygen and the hydrogen on the spot and we have the capacity for three full fillings [of the Ariane rocket]," explained Daniel Neuenschwander, the director of space transportation at Esa.

The Ariane carries a number of modifications for the upcoming flight.

In particular, special vents have been put in the sides of the nose cone fairing to ensure there is an even loss of pressure during the climb to orbit. This will ensure there is no abrupt change in environment that might damage the telescope when the fairing panels are discarded.

The rocket will throw Webb on to a path that will take it to an observing station some 1.5 million kilometres from Earth.

This journey should last a month, during which time the telescope will unfold its 6.5m-diameter primary mirror and the tennis court-sized shield intended to protect its observations of the cosmos from the Sun's light and heat.

Webb's goal is to image the earliest objects to form after the Big Bang.

These are theorised to be colossal stars, grouping together in the first galaxies.

Webb will also probe the atmospheres of planets outside our Solar System - so-called exoplanets - to see if they hold gases that might hint at the presence of biology.

"Webb will have an opportunity to study these exoplanets and answer the fundamental questions that we astronomers ask ourselves, and the public alike - are we alone? Is Earth unique? Do we have other planets out there that can host life? These are very ambitious questions that speak to all of us," said Antonella Nota, Esa's Webb project scientist.

Our last view of Webb on Earth as it disappears under the rocket's nose cone