James Webb: Weather shifts telescope launch to 25 December

- Published

Watch engineers attach James Webb to its Ariane rocket

A poor weather forecast has pushed back the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope by a further day.

Concerns about high-level winds at the Kourou spaceport in French Guiana mean it won't now happen until 25 December.

Everything is set, though. A readiness review for the rocket and the observatory is complete, and launch teams have conducted their final rehearsal.

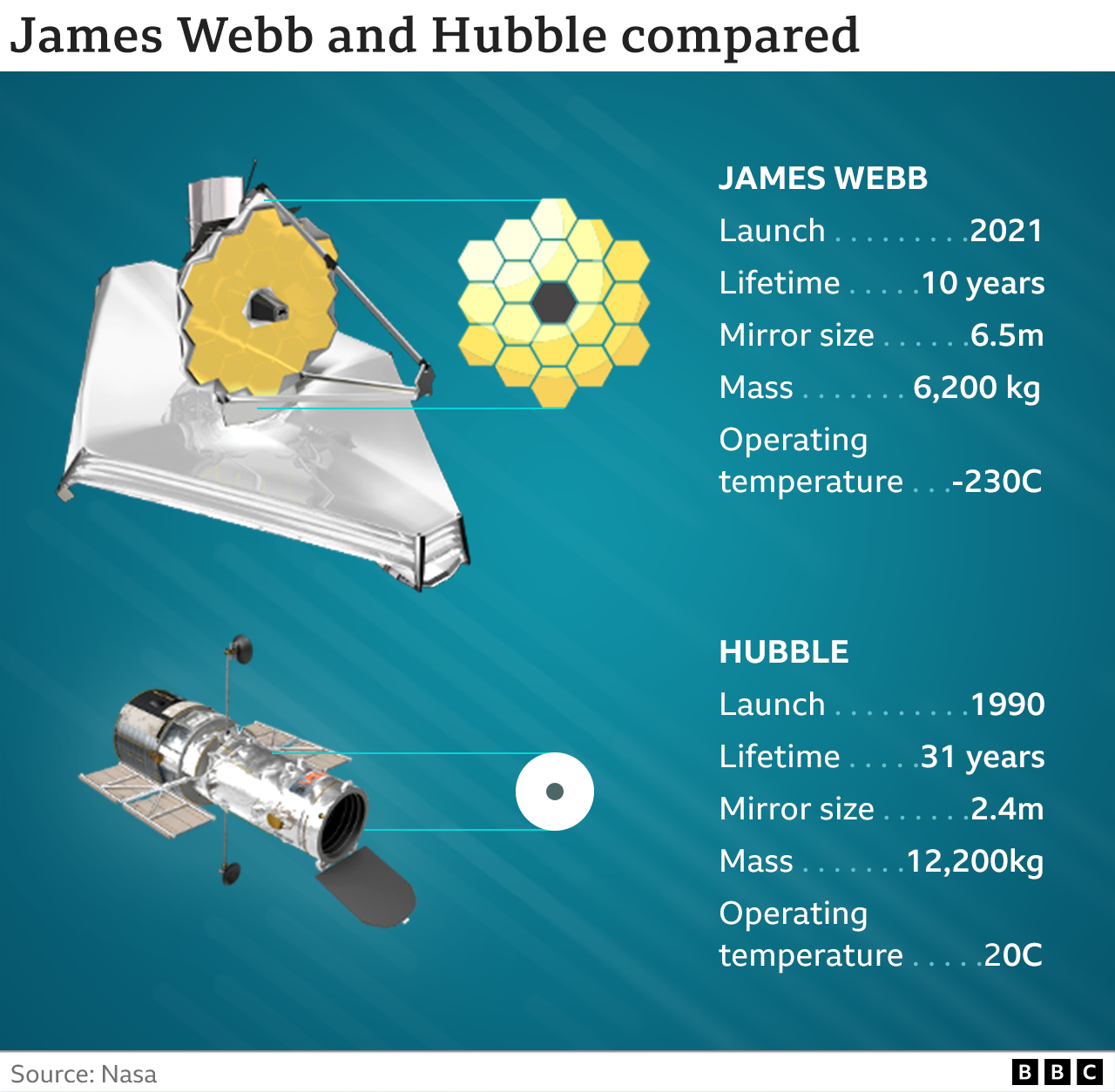

Webb is the $10bn (£7.5bn) successor to the Hubble Space Telescope.

The new observatory has been designed to look deeper into the Universe than its predecessor and, as a consequence, detect events occurring further back in time - more than 13.5 billion years ago.

Scientists also expect to use its more advanced capabilities to study the atmospheres of distant planets in the hope that signs of life might be detected.

"This is an extraordinary mission. It's a shining example of what we can accomplish when we dream big," said US space agency (Nasa) administrator Bill Nelson.

"This is the kind of mission that only Nasa and our partners can carry out. It's going to give us a better understanding of our Universe and our place in it.

"Who we are. What we are. The search that is eternal. Why are we here? How did we get here?"

The Webb project is a partnership between Nasa and the European (Esa) and Canadian space agencies (CSA).

It is Esa which has taken on the responsibility for launch, making available one of its dependable Ariane 5 rockets for the ascent to orbit.

Preparation on the vehicle and telescope was completed at the weekend, the observatory encapsulated behind the Ariane's nosecone.

The environment under the fairing is being carefully monitored, and constantly purged with filtered, dry air.

Arianespace, the company that manages launches at Kourou, will issue another weather bulletin on Wednesday. If conditions still don't look good, the launch attempt will be moved to Sunday, 26 December.

Only when a launch looks likely will the rocket, with Webb atop it, be rolled out to the pad. For a flight on 25th, this would happen on Thursday.

Your device may not support this visualisation

High-level winds blowing in the wrong direction have to be taken into account, not because the rocket itself is incapable of handling them, rather it's because controllers want to avoid debris falling back on land in the event of a launch failure.

Whichever day is chosen, the lift-off time is likely to be the same - 09:20 local (12:20 GMT). Controllers will be given a half-hour window to get the Ariane airborne, but will target the very beginning of this time period.

The Ariane will head east out of Kourou, over the Atlantic towards Africa. The ascent is scheduled to last 27 minutes. A radio signal confirming separation of the telescope from the rocket's upper-stage will be picked up by a ground antenna at Malindi in Kenya.

Video cameras have been put on the Ariane to relay the moment back to Earth.

Webb is being sent to an observing station some 1.5 million km (932,000 miles) from Earth.

This journey should last a month, during which time the telescope will unfold its 6.5m-diameter primary mirror and the tennis court-sized shield intended to protect its observations of the cosmos from the Sun's light and heat.

Apart from its greater size and updated technologies, Webb's key difference from Hubble is that it has been tuned to see the cosmos predominantly in the infra-red. Hubble's vision was mainly in those frequencies we detect with our own eyes - so-called optical, or visible, light.

The longer wavelengths of the infra-red will allow Webb to see things that are denied to other telescopes.

"We can peer into dust, because long wavelengths are much more effective at seeing through dust," said Prof Gillian Wright, the European principal investigator on Webb's Mid-Infrared Instrument (Miri)

"We know that stars and planets form in very dusty regions. So if we want to study more about how stars and planets form, Miri has got a critical role."

This is how Kourou launch director Jean-Luc Voyer will call the countdown