James Webb Space Telescope: Sun shield is fully deployed

- Published

This is Webb's current configuration. Its shield is deployed but its mirrors are still stowed

The new James Webb telescope has passed a major milestone in its quest to image the first stars to shine in the cosmos.

Controllers on Tuesday completed the deployment of the space observatory's giant kite-shaped sun shield.

Only with this tennis court-sized barrier will Webb have the sensitivity to detect the signals coming from the most distant objects in the Universe.

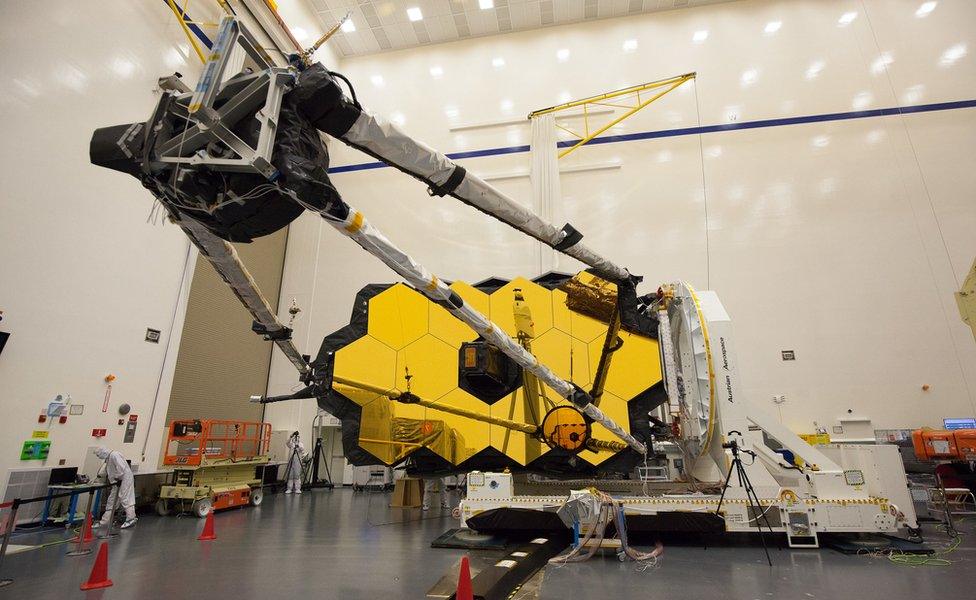

Commissioning work will now concentrate on unpacking the telescope's mirrors, the largest of which is 6.5m wide.

Watch the moment Webb moves away from its launch rocket to begin its mission

The deployment of the five-membrane sun shield is a triumph for the engineering teams at the US space agency (Nasa) and the American aerospace manufacturer Northrop Grumman.

There were many who doubted the wisdom of a design that included so many motors, gears, pulleys and cables.

But years of testing on full-scale and sub-scale models paid dividends as controllers first separated the shield's different layers and then tensioned them.

The fifth and final membrane - which like the other four had the thickness of a human hair - was locked into place at 16:58 GMT.

"Unfolding Webb's sun shield in space is an incredible milestone, crucial to the success of the mission," said Greg Robinson, Webb's program director at Nasa Headquarters.

"Thousands of parts had to work with precision for this marvel of engineering to fully unfurl. The team has accomplished an audacious feat with the complexity of this deployment - one of the boldest undertakings yet for Webb."

It's worth noting that all the previous testing was done on Earth, under gravity conditions. This was the first time the shield had been unfurled in the unique "Zero-G" environment of space. "The first time, and we nailed it," enthused Alphonso Stewart, Nasa's Webb deployment systems lead.

"There was a lot of joy, a lot of relief," added Hillary Stock, the sunshield deployments lead at Northrop.

James Webb was launched on 25 December on an Ariane rocket from French Guiana.

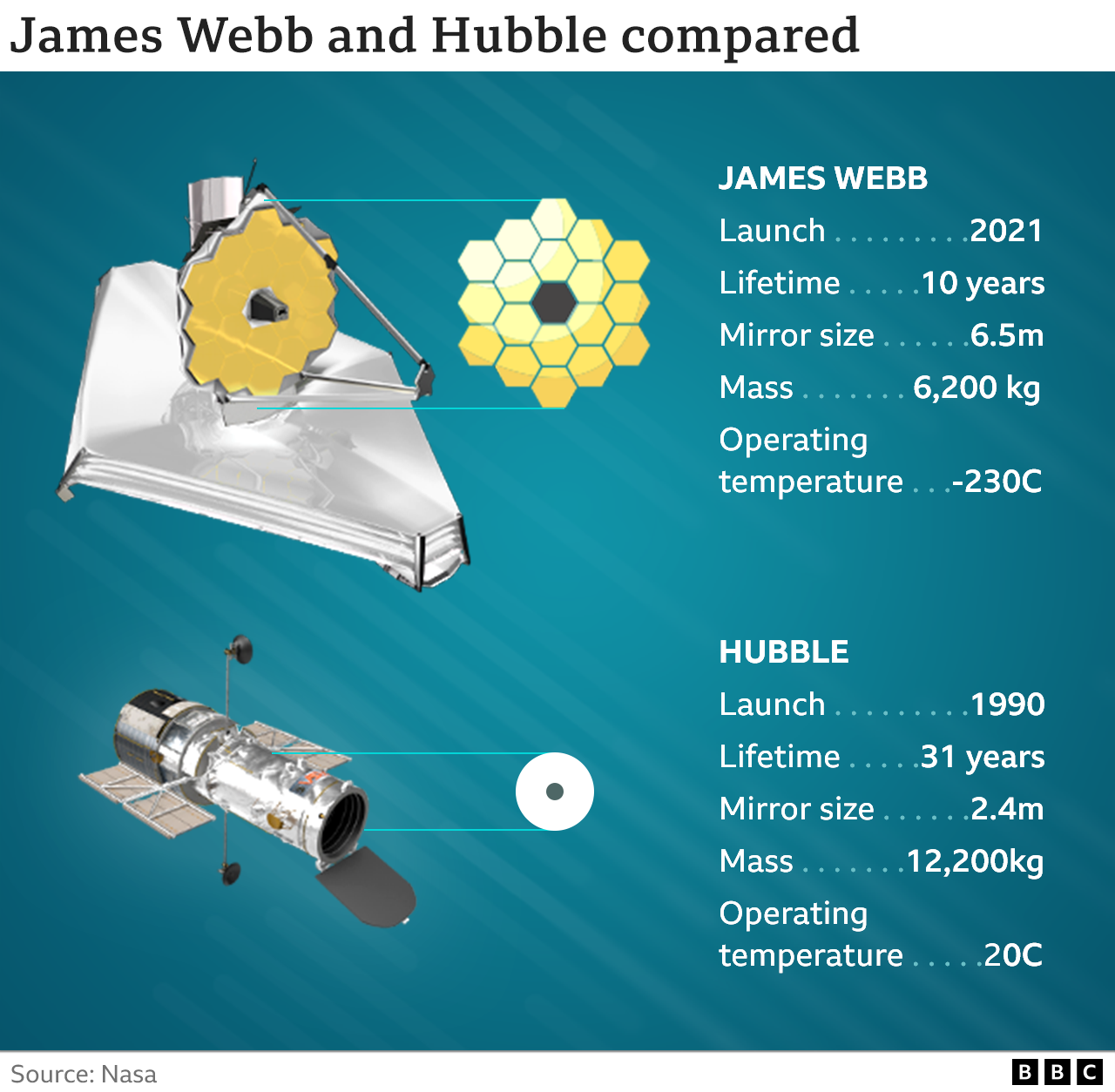

The telescope is regarded as the successor to the Hubble space observatory which is now 31 years old and nearing the end of its operational life.

Webb will do similar science to Hubble but with the next-generation technologies that allow it to see deeper into the cosmos and, therefore, further back in time.

The expectation is that it will even catch the light from the pioneer stars that were first to ignite shortly after the Big Bang more than 13.5 billion years ago.

Critical to the whole endeavour, however, will be Webb's sensitivity in the infrared. The light coming to the telescope from its targets at the edge of the observable Universe will arrive in this longer wavelength domain. And that means Webb must be cooled to fantastically cold temperatures or its own infrared glow will swamp the signals it's trying to detect.

Hence the shield. The shade it casts will lower the environment around Webb's mirrors and instruments to below minus 230C.

The secondary mirror is extended on 8m-long booms in front of the main mirror

The controllers, who are based at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland, now have Webb's golden mirrors in their sights.

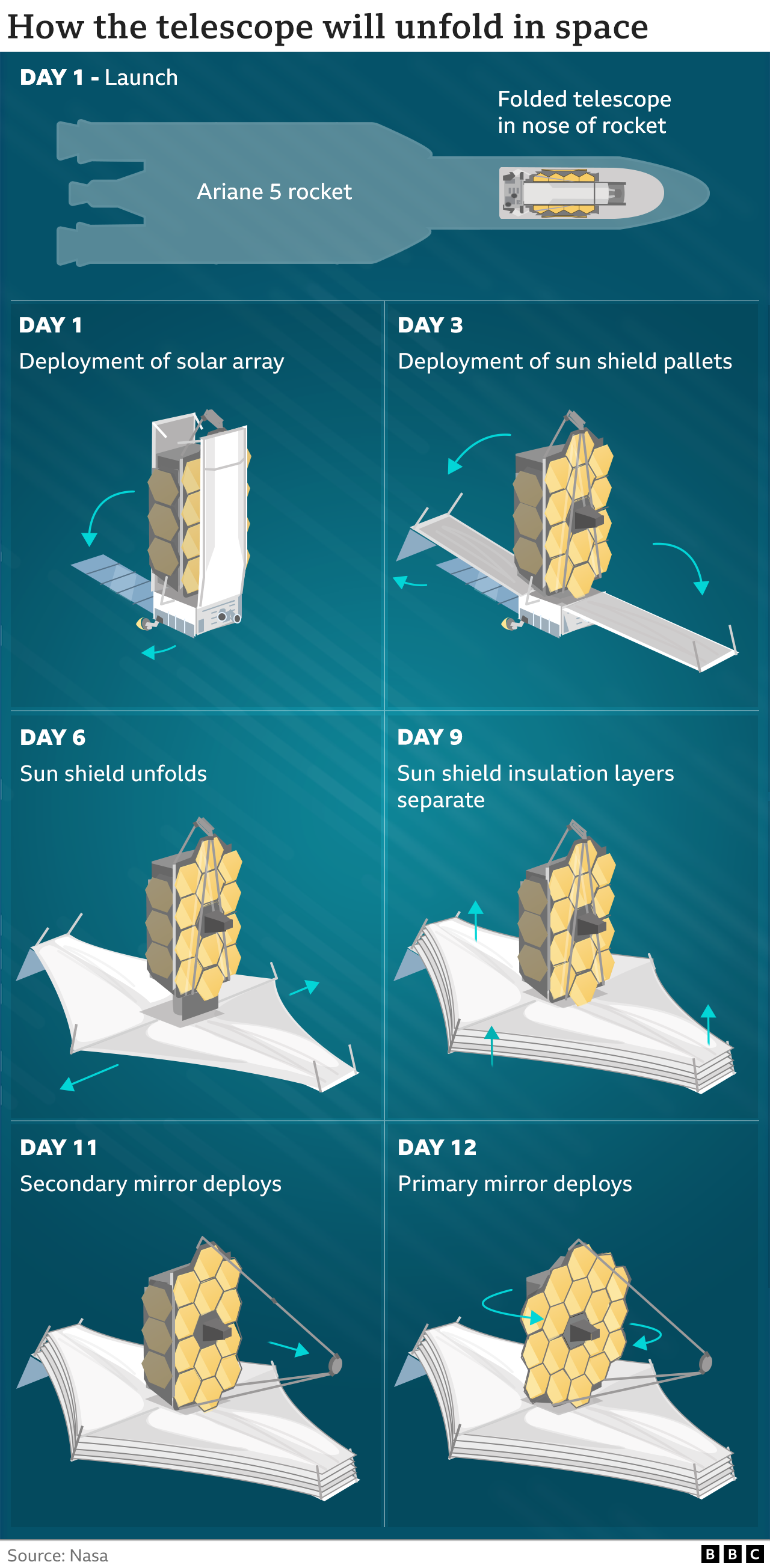

Like the sun shield, the telescope's two principal reflectors had to be folded to fit inside the nosecone of the Ariane.

Wednesday should see the 74cm-wide secondary mirror extended on 8m-long booms in front of the primary mirror.

The main mirror has "wings" that were tucked back for launch but which must now be rotated through 90 degrees to make a full, 6.5m-wide surface. Assuming things continue to run like clockwork, this should happen at the end of the week.

Webb is currently moving out to a position 1.5 million km from Earth on the planet's "midnight" side. It's from this location that it will study the Universe.

James Webb is a joint venture between the American, European and Canadian space agencies.