James Webb telescope completes epic deployment sequence

- Published

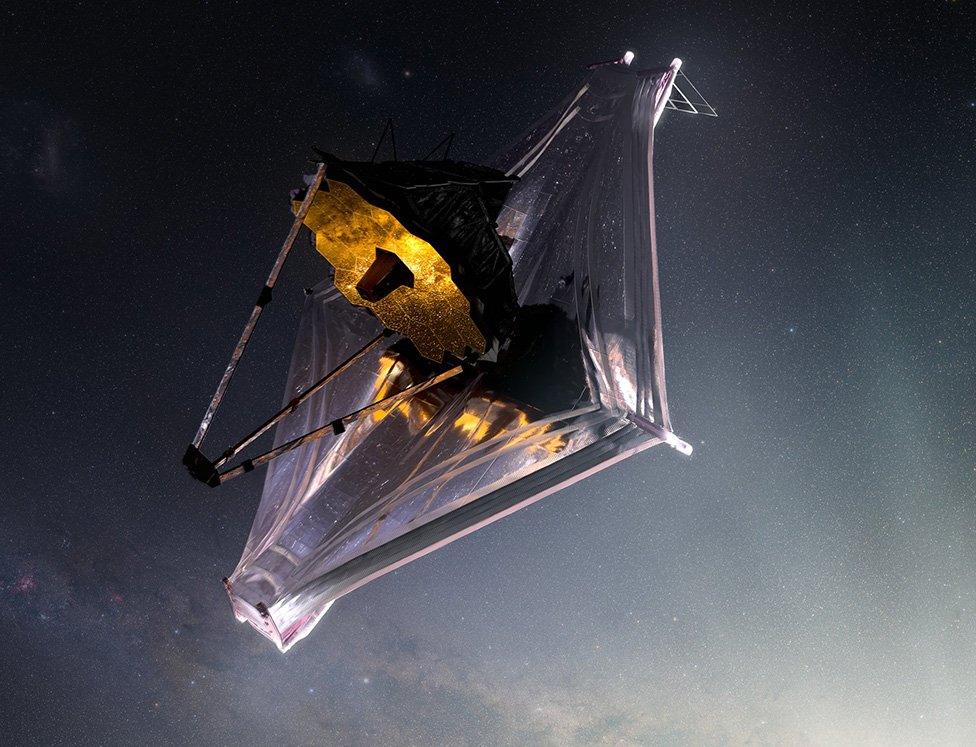

Artwork: Webb is now in the designed configuration to view the cosmos

It's done. The biggest astronomical mirror ever sent into space is assembled and ready for focusing.

The golden reflector, the centrepiece of the new James Webb telescope, was straightened out on Saturday into its full, 6.5m-wide, concave shape.

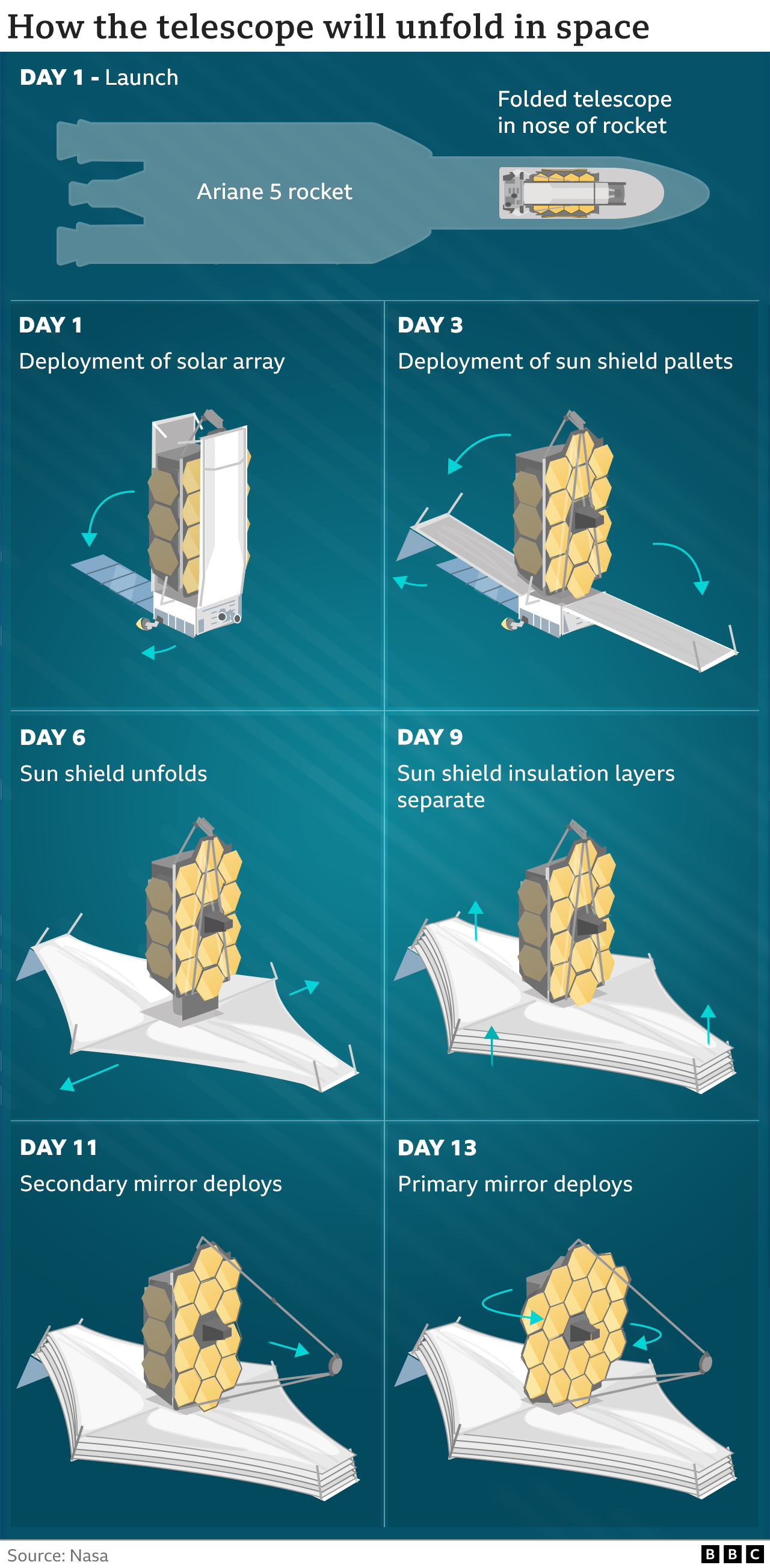

The mirror had been folded like a drop-leaf table for the mission's Christmas Day launch.

James Webb is set now to become a transformative tool in the study of all parts of the cosmos.

Controllers at the Space Telescope Science Institute celebrate mirror deployment

Scientists intend to use the $10bn observatory and its remarkable mirror to capture events that occurred just a couple of hundred million years after the Big Bang. They want to see the very first stars to light up the Universe.

They'll also train the telescope's big "eye" on the atmospheres of distant planets to see if those worlds might be habitable.

"Webb has the potential to blow people away, even people who are used to the pictures from the Hubble Space Telescope - and I know that's hard to imagine," said Lee Feinberg, who's led the Webb mirror development team at the US space agency (Nasa).

"Webb is so powerful, almost anywhere we look we're going to be breaking new ground in a huge way," he told BBC News.

Webb was sent up with the sides of its main mirror folded like a drop-leaf table

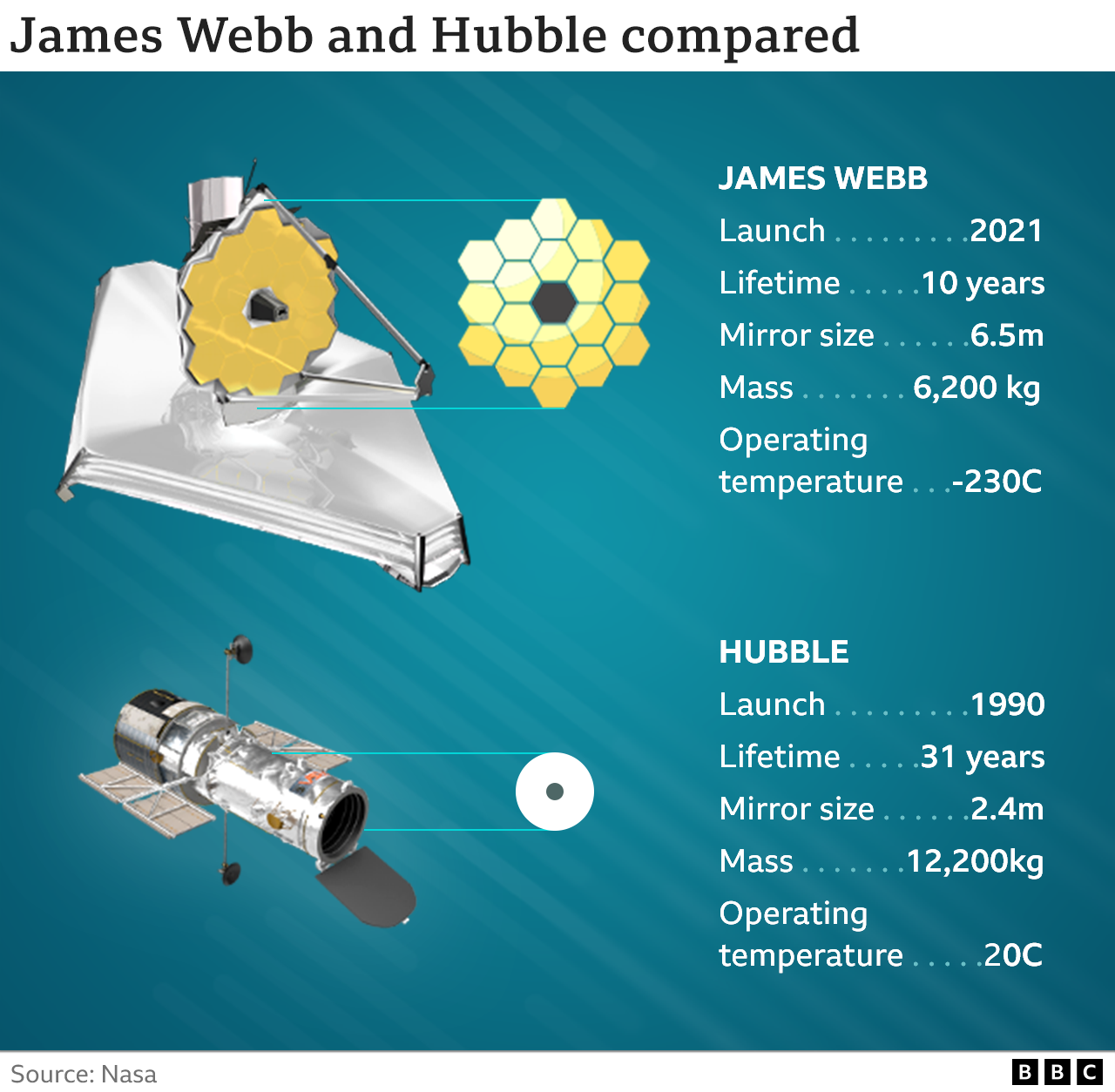

The telescope is a joint project of the American, European and Canadian space agencies. It has taken 30 years to design and build, and will continue the revelatory science of Hubble, which is now nearing the end of its operational life.

Webb carries next-generation technologies. It's also much bigger. It's so big, it had to be flat-packed to fit inside the nosecone of the European Ariane rocket that took it to orbit on 25 December.

The subsequent unwrapping over the past fortnight has had everyone holding their breath. But the complex series of deployments, which included the unfurling of a tennis-court-sized sun shield, passed off with no drama.

It will go down in space exploration history as an astonishing accomplishment.

Expectations are now sky high

It's time for astronomers to breathe a sigh of relief.

Usually it's the launch that's the most nail-biting part of a mission but the last two weeks have been even more nerve-wracking. Unfolding a telescope of such colossal proportions has been one of the most challenging deployments ever attempted in space.

But team Webb has done it. And, in fact, it's gone so smoothly, they've made the task look easy. The decades of work on the telescope's design and its innovative engineering have clearly paid off.

The real proof of the observatory's power though won't come until this summer when the first images are captured and beamed back to Earth. And expectations are sky-high - the views should not only be spectacular but they could also answer some of the biggest questions - like how did our Universe begin and does life exist beyond the Earth?

Webb has a lot of promise to live up to.

Controllers, based at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland, completed the rearrangement sequence by rotating the main mirror's two "wings" through 90 degrees.

Telemetry beamed down from Webb confirmed the second of these side panels had been latched and locked in place at 18:16 GMT.

"We have a fully deployed JWST observatory," Carl Starr, the mission operations manager at STScI, announced.

"The last two weeks have been totally amazing," added Bill Ochs, the Nasa Webb programme manager. "Thousands of people have worked on JWST to get us to this point. I will tell you every single day that I am honoured and humbled to be associated with this team."

And addressing controllers, Thomas Zurbuchen, the director of science at Nasa, said: "We have a deployed telescope on orbit, a magnificent telescope the likes of which the world has never seen. So, how does it feel to make history everybody?"

There is still much to do to get James Webb ready to image the Universe. The initial task is simply to let it get very cold.

The telescope is designed to work in the infrared. It's at this longer wavelength of light (longer than we can see with our eyes) that the pioneer stars will be observed to shine. But unless Webb is taken down to a super-low temperature, its own heat energy will swamp the faintest of signals.

"We'd be blotting out the very thing we want to see; it would be like trying to look at a lighted match in front of a burning haystack. You'd be lost," said Gillian Wright, one of Webb's principal investigators.

Hubble's pictures transformed our view of the cosmos. Webb's should be no less impressive

The big shield will produce a shadow from the Sun that will eventually put Webb below -230C.

Only in this frigid condition will the four scientific instruments onboard have the required sensitivity.

Engineers will begin checking over their function and performance shortly. They'll also have to align all 18 hexagonal segments in the main mirror to make them behave like a single monolithic reflecting surface.

Each of the segments has motors at the rear that can move them up and down, tip them sideways, rotate them, and even slightly bend them to give them exactly the right curvature.

All of this preparatory work will fill the next five months or so. The first public release of pictures from Webb is not expected until the end of June at the earliest. But we should be prepared to be wowed, say space agency officials.

"Webb is an engineering marvel, but it also has this beauty to it," enthused Lee Feinberg.

"One of my favourite things was to watch people's faces when they walked up and looked at it. There is a feeling of awe that humans created this thing. It's just the size and the scale, and the gold coatings. It really lifts you up," he told BBC News.

Webb was funded for an initial five years of operations with an expectation it could work for about 10. The life-limiting factor has always been considered to be the amount of fuel onboard the telescope to maintain positioning in space. But such was the accuracy of the launch rocket in putting Webb in just the right part of the sky, astronomers can now look forward to a much longer lived observatory.

"We have quite a bit of fuel margin right now relative to 10 years. Roughly speaking, it's around 20 years of propellant," said Mike Menzel, Nasa's Webb mission systems engineer.

"There is a feeling of awe that humans created this thing"