A68: 'Megaberg' dumped huge volume of fresh water

- Published

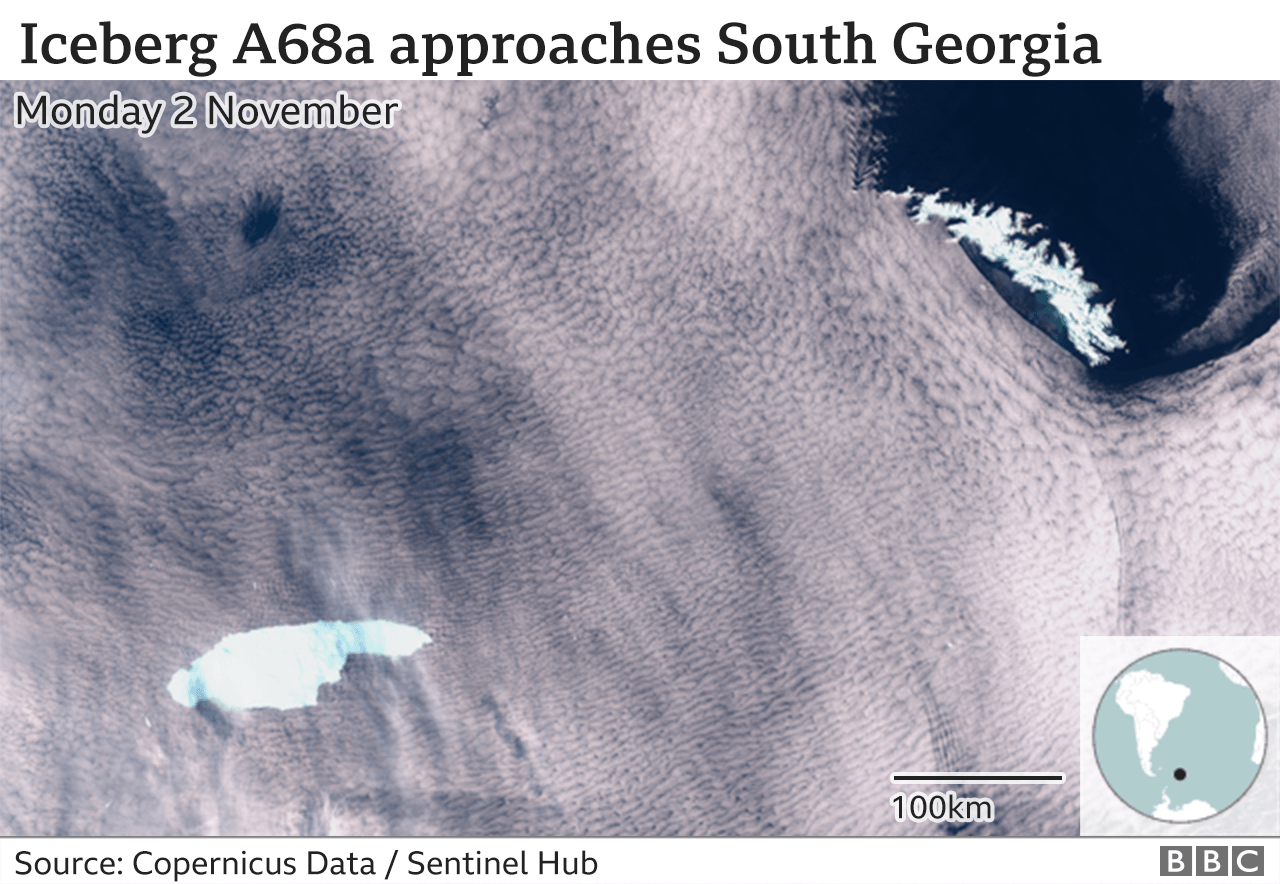

In late 2020, the iceberg was bearing down on South Georgia

The monster iceberg A68 was dumping more than 1.5 billion tonnes of fresh water into the ocean every single day at the height of its melting.

To put that in context, it's about 150 times the amount of water used daily by all UK citizens.

A68 was, for a short period, the world's biggest iceberg.

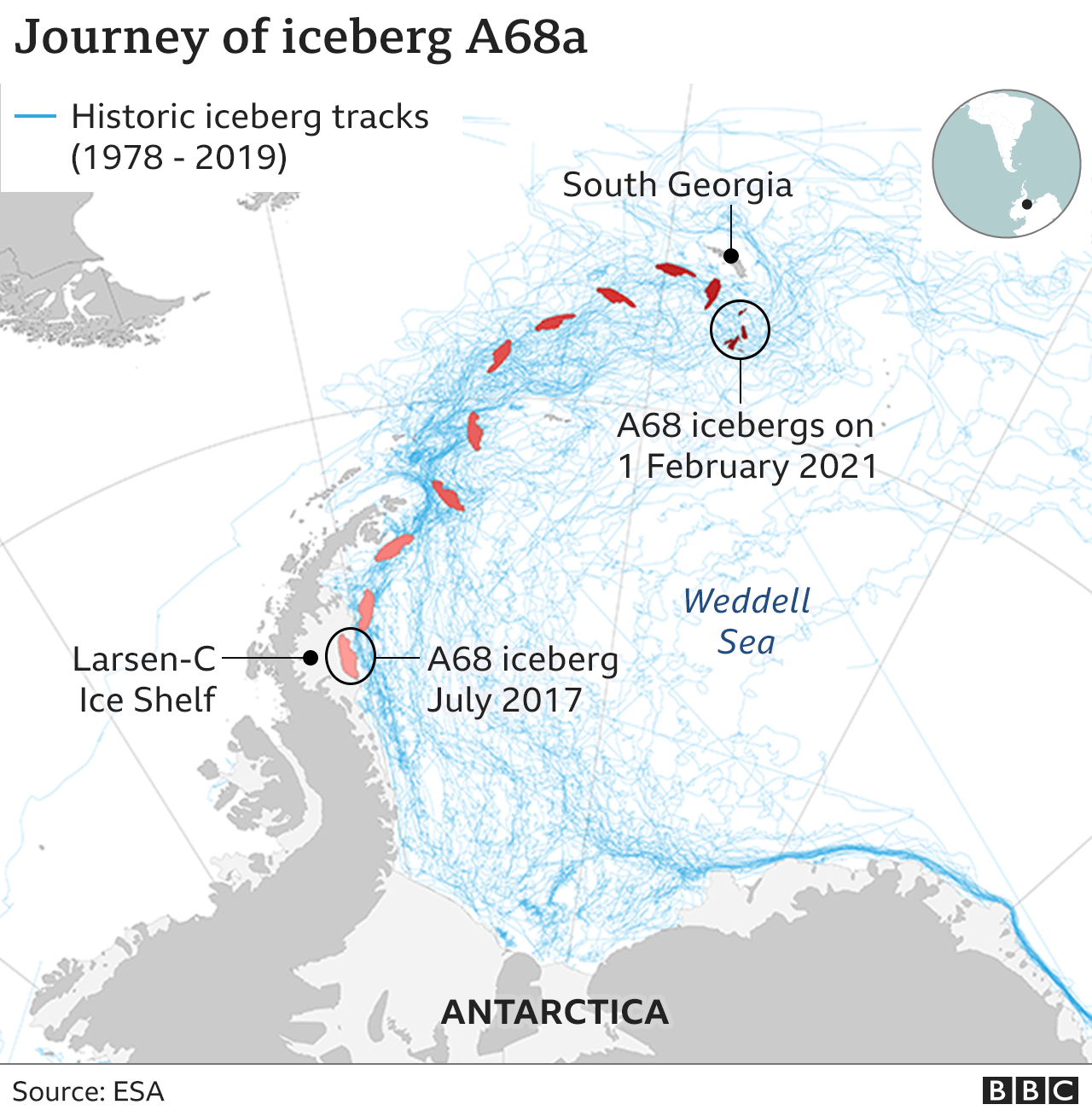

It covered an area of nearly 6,000 sq km (2,300 sq miles) when it broke free from Antarctica in 2017. But by early 2021, it had vanished.

One trillion tonnes of ice, gone.

Researchers are currently busy trying to gauge the impact A68 had on the environment.

And a team led from Leeds University has been back through all the satellite data to calculate the behemoth's changing dimensions as it moved north from the White Continent, through the Southern Ocean and up into the South Atlantic.

This has enabled the group to assess varying melt rates during the course of the megaberg's three-and-a-half-year existence.

One of the key periods, obviously, was towards the end, as A68 approached the warmer climes of the British Overseas Territory of South Georgia.

Watch: The RAF flies over the huge iceberg

For a while, there were fears the giant block could ground in the surrounding shallows, blocking the foraging routes of millions of penguins, seals and whales.

But it never quite happened because, as the team can now show, A68 lost sufficient depth of keel to stay afloat.

"It does seem that it briefly touched the continental shelf. That's when the berg took a turn and we saw a small piece break off. But it wasn't enough to ground A68," lead author Ms Anne Braakmann-Folgmann from the Nerc Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling at Leeds told BBC News.

"And I think you can see why in the thickness estimates," added co-author Prof Andrew Shepherd. "By that stage the berg's keel was 141m, on average, and the bathymetry (depth) charts in the area showed 150m. It was a close call in the end."

By April 2021, A68 had broken into countless small fragments that were beyond tracking. But its ecosystem impacts will have been much longer-lived.

Wide but extremely thin: In the beginning, A68 had an average thickness of 235m

Giant tabular, or flat-topped, bergs are now recognised to have considerable influence wherever they roam.

Their freshwater inputs will alter local currents. And all the iron, other minerals, and even organic matter picked up through their lives and subsequently dropped into the ocean will seed biological production.

The British Antarctic Survey managed to place some robotic gliders in the vicinity of A68 to monitor conditions before the ice mass totally wasted away.

The data retrieved from these and other instruments, although not yet fully analysed, was revealing some interesting features, said biological oceanographer Prof Geraint Tarling.

"We think there's a really strong signal in the changing flora of the phytoplankton species around A68, and also in the actual deposition of material to the deeper parts of the ocean. The particle sensor on the glider was picking up some very strong signals of deposition coming from the berg," he told BBC News.

Details of A68's changing shape and freshwater fluxes are contained in a paper published in the journal Remote Sensing of Environment, external.