Shackleton's Endurance: The impossible search for the greatest shipwreck

- Published

Endurance set sail from Grytviken, South Georgia, on 5 December 1914 (Oil painting by George Cummings)

It is one of the most unreachable shipwrecks in the world.

We know with good accuracy where Sir Ernest Shackleton's Endurance vessel ended up after sinking more than 100 years ago. So far, however, all attempts to sight its wooden carcass on the Antarctic seafloor have been defeated.

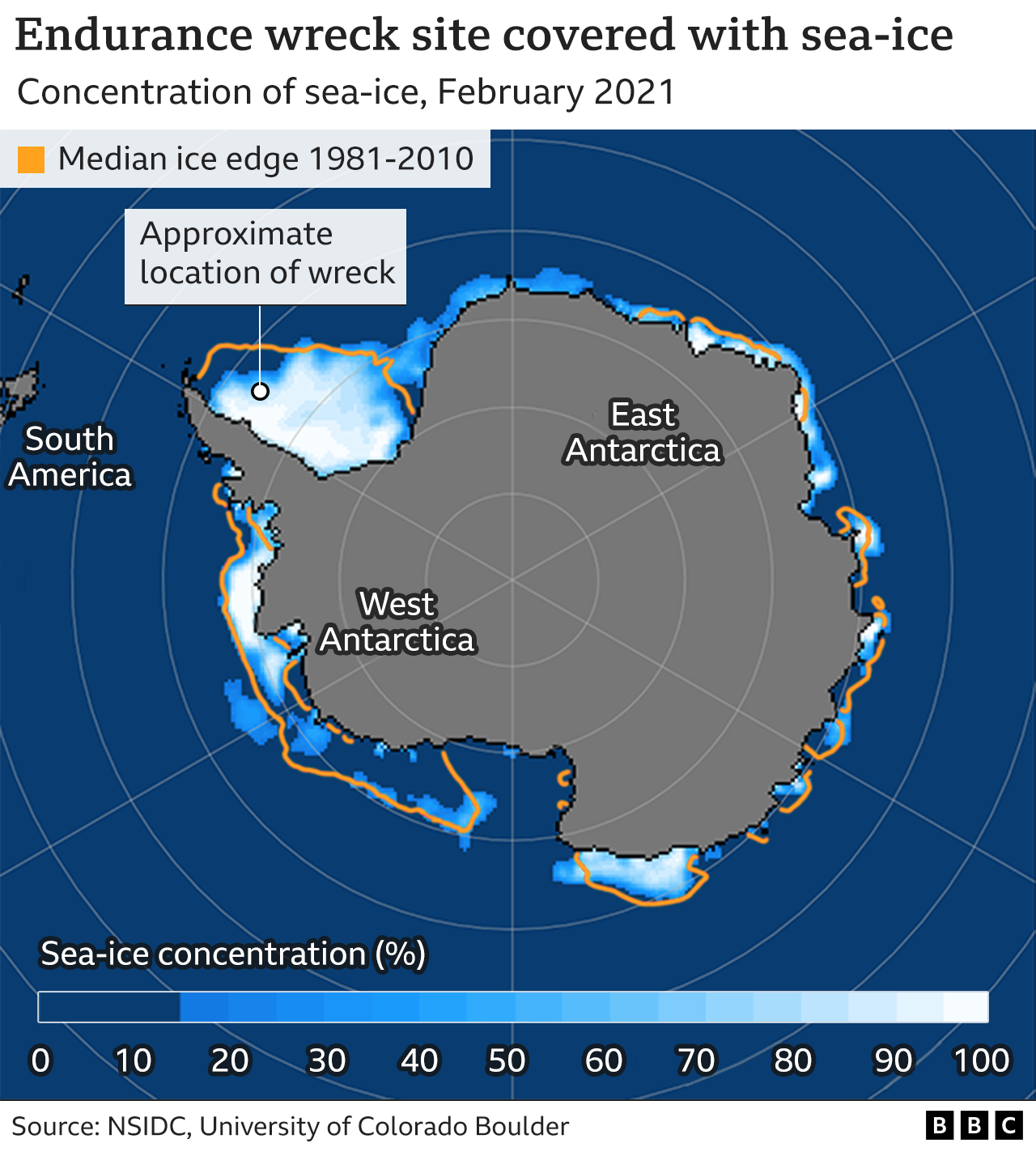

Although it's deep, some 3,000m down, that's not the major difficulty a new expedition to find the ship will face. It's the sea-ice. The cruel, evil sea-ice, as the Anglo-Irish explorer Shackleton came to think of it.

The frozen floes that squeezed, snapped and then swallowed his polar steam yacht in the Weddell Sea between October and November 1915 smother its grave and protect it from discovery.

Even in this age of satellites and metal icebreakers, locating the Endurance has represented an impossible task.

"Believe me, it's quite daunting," says Mensun Bound, the marine archaeologist who's about to set out on yet another search attempt.

"The pack ice in the Weddell Sea is constantly on the move in a clockwise direction. It's opening, it's clenching and unclenching. It's a really vicious, lethal environment that we're going into."

So, why bother? Why put yourself forward again for what seems inevitable disappointment?

Well, that's the fascination with Shackleton.

Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition lasted from 1914 to 1917. It was meant to make the first land crossing of Antarctica, but Endurance became trapped and then lost in that cruel sea-ice. The voyage became widely known for the amazing escape the explorer subsequently made with his men on foot and in boats.

It's the stuff of legend. That's the appeal.

Mensun Bound asks: "What would it mean to find the Endurance?"

He adds: "This is the greatest shipwreck hunt you can undertake. To locate it - it doesn't get better than that. So, by definition, my life would be downhill afterwards."

Shackleton's diary records the day the Endurance went down

The archaeologist is part of the Endurance22 project, external. Its hunt for Shackleton's missing ship is organised by the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust, and departs from Cape Town this weekend.

Search team members include key figures who came tantalisingly close to finding the wreck in 2019.

Operating from the South African-registered research ship, the Agulhas II, this earlier effort actually managed to get over the sinking location, recorded by Shackleton's skipper and skilled navigator, Frank Worsley, as 68°39'30" South and 52°26'30" West.

Once on site during this previous expedition, they deployed an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) to survey the seafloor, but after 20 hours below, the robot dropped communications and that wretched sea-ice then closed in to force the Agulhas II to retreat.

Endurance22 expedition leader, Dr John Shears, says important lessons were learned and the new team goes back with a few tricks, which include the support of helicopters.

"We'll deploy our search submersible from the aft deck of the Agulhas. But we wanted to have the contingency that if we hit really severe ice conditions and we can't get over the wreck site, then we can fly an 'ice camp' to the search location," the veteran polar geographer tells me.

"We'd put down on the ice and drill through it, and deploy our underwater vehicle that way."

The team has recently been practising its hydraulic drilling technique on specially prepared 3m-thick "ice cubes".

Even in the austral summer, the central-western Weddell Sea is covered in sea-ice

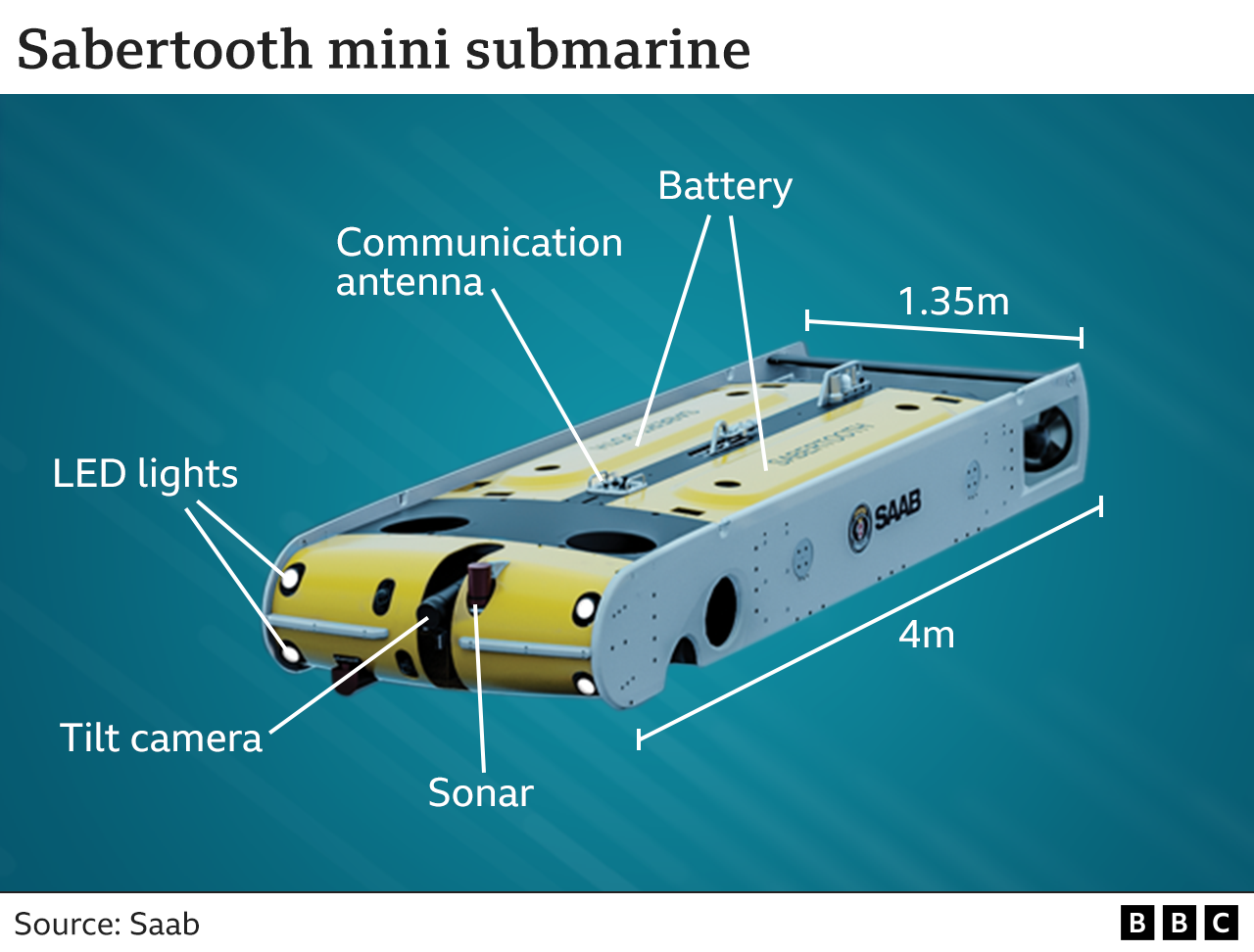

The sub technology is different this time, too.

In 2019, a Kongsberg Hugin AUV was used. When it ran its sweep of the seafloor, no data on what it was sensing was sent to the surface in real time. As a consequence, when the sub failed, all the mapping information it had collected was also lost.

For this latest search, the chosen submersible - a Saab Sabertooth - will be tethered via a fibre-optic cable. If the wreck is sighted, the survey will be halted and the process of documentation will immediately begin.

"The Sabertooth is fitted with long-range side-scan sonar which supplies images of the seabed to you on the topside (on the surface), either on board the ship or in the tent of the ice camp," says Nico Vincent, who'll oversee the operation.

"If a target appears beside the vehicle, we can, at the flick of a switch, interrupt the task plan and fly like a drone to the target to double-check it."

Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

The entire crew survived the ship's loss in the ice

December 1914: Endurance departs South Georgia

February 1915: Ship is thoroughly ice-locked

October 1915: Vessel's timbers start breaking

November 1915: Endurance disappears under the ice

April 1916: Escaping crew reaches Elephant Island

May 1916: Shackleton goes to South Georgia for help

August 1916: A relief ship arrives at Elephant Island

Endurance22 has two Sabertooths that will work around the clock.

The search area is relatively small: just 8km by 15km (4 by 8 nautical miles). But such was Worsley's genius with a sextant and a chronometer - maritime navigation instruments - there's high confidence in his calculated coordinates.

One of the big questions concerns the likely state of the wreck. The water is too deep for the remnants to have been bulldozed by a passing Antarctic iceberg.

Sediment is building up slowly enough on the wreck that the timbers are probably still standing proud of the seafloor, but they could be spread out over a large distance. And, of course, there's every possibility that Endurance was wrenched wide open on impact with the bed, its contents "exposed like a box of chocolates", as Mensun Bound puts it.

The only known relic from Endurance is this spar (a pole that's part of the ship's rig) at the Scott Polar Research Institute

While the type of worms that normally consume sunken wooden ships do not thrive in the cold conditions of the polar south, the Weddell's bottom-waters are almost certainly well oxygenated, which means many other types of organisms could still have colonised the wreck.

"Anything hard that sticks out above the sediment is fabulous, rare real estate," says Dr Michelle Taylor, a deep-sea biologist who took part in the 2019 hunt but is not involved in this latest quest.

"If you get yourself even just a few centimetres above the sediment into the flow of the current, you're more likely to feed and survive. So, like boulders dropped to the sea-floor by passing icebergs, the Endurance will probably be an oasis for life. It should attract a lot of filter feeders, such as crinoids. And I wouldn't be surprised if we see some anemones and some sea-cucumbers," the Essex University scientist told the BBC.

Shackleton (L) looks over the broken remains of his ship just before it went to the deep

What, though, does it really add to the Shackleton story if we see its sad, shattered hull 100 years after it sank to the deep?

The drama and heroics were well documented at the time. We have the crew's diaries and there are no mysteries about what happened.

Some polar researchers have told me that the money behind Endurance22 would be better spent on a dedicated science voyage in the Antarctic. It's the "climate front line" after all, and there's much we still need to study and learn about what is going to happen to the White Continent in a warming world.

But the allure of Shackleton is strong.

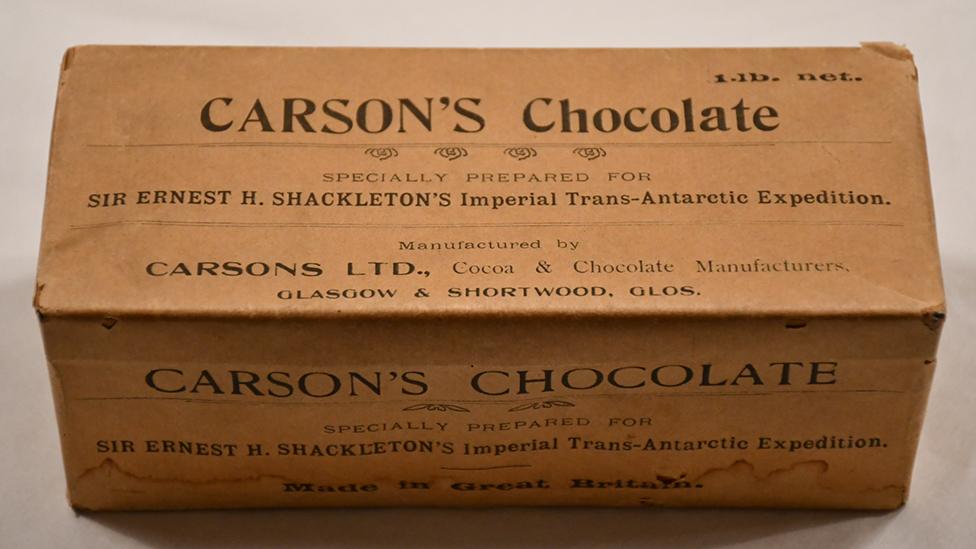

A few artefacts from the expedition remain, but so much else is at the bottom of the ocean

There's no doubting there would be considerable curiosity in video of the wreck and the sight of the crewmen's belongings which may be strewn around it.

Somewhere down there is the storekeeper Thomas Orde-Lees' bicycle; the honey jars in which expedition biologist Robert Clark kept his samples; and the rocks geologist James Wordie collected from the bellies of penguins.

"We may see supplies, or we may see things that connect us with the actual people who over 100 years ago had to abandon this ship, live on the ice and then take brutal small-boat journeys to safety," says historian Dan Snow, who will be travelling on the expedition.

"I hope and think the wreck will have lots of interest, not just for the super-geeks like me but there'll be stuff that will enrich the story for everyone."

Even in the age of satellites and metal icebreakers, the Weddell Sea is a notoriously inhospitable place

If Endurance22 succeeds in finding the lost ship, no artefacts will be pulled up.

The vessel is a site of historic importance and has been designated as a monument under the international Antarctic Treaty. It mustn't be disturbed.

Mensun Bound says the team will instead make a highly detailed 3D scan.

"There's no point raising something like the Endurance, anyway. What would you do with it? There isn't a museum on Earth that could accept it. The cost of its conservation, preservation and display would be at any museum's throat forever."

The BFI has re-mastered the moving footage of Endurance that was captured by Shackleton's expedition photographer, Frank Hurley. SOUTH (1919) is now in cinemas, external. Dan Snow will be reporting on the progress of the search through his HistoryHit, external channels.