Peat soil fires: Campaigners say England's 'rainforests' illegally burned

- Published

- comments

The scars of burning on deep peat in the Yorkshire Dales National Park

Some shooting estates in England burn deep peat moorland in protected areas despite a government ban, say the RSPB and Greenpeace.

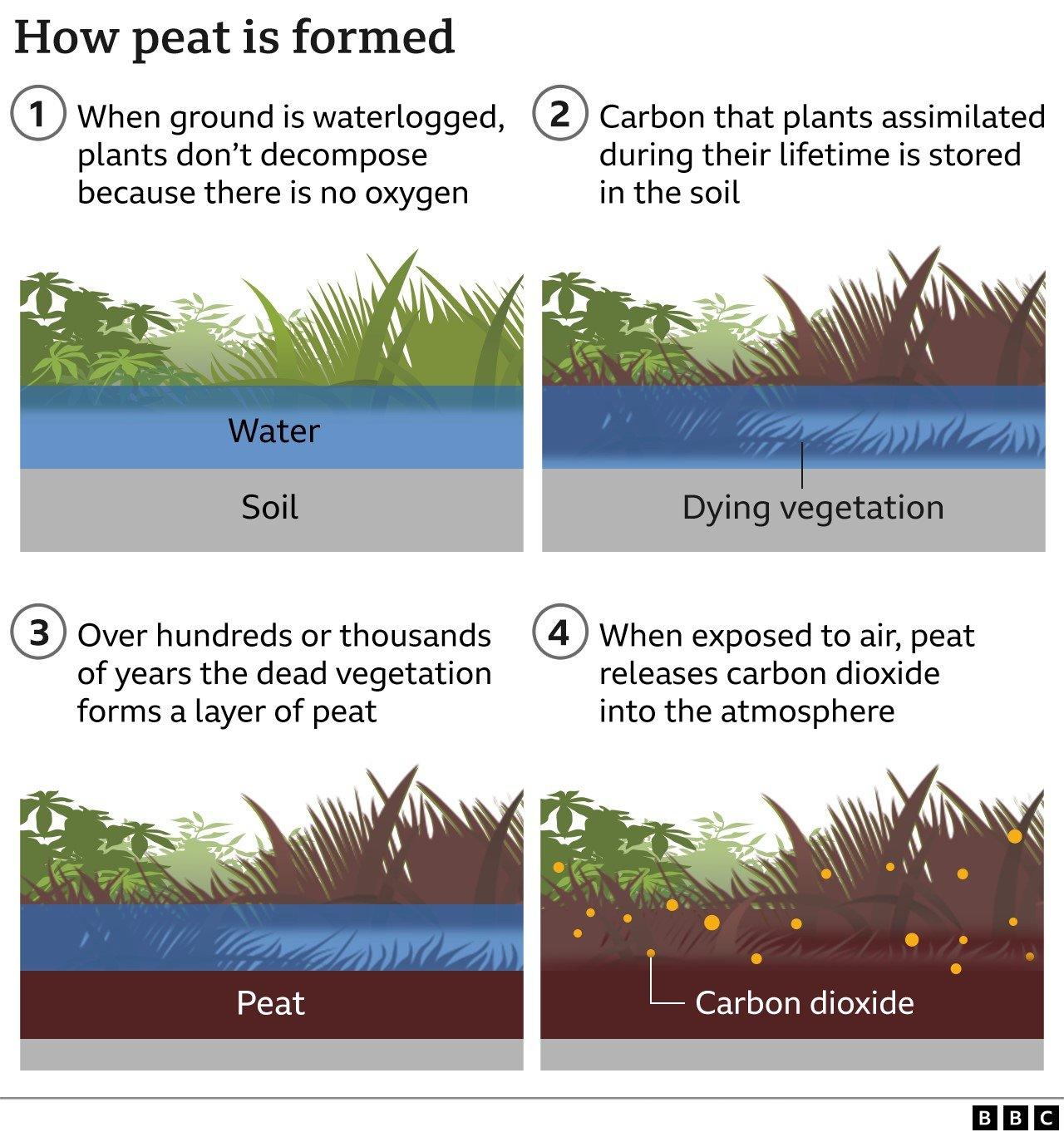

England's deep peat soils support rare ecosystems and store huge amounts of carbon.

Peatland vegetation has traditionally been burnt to create and maintain habitats to raise grouse for shooting.

The government last year introduced a ban on burning peat deeper than 40cm in some protected areas of England.

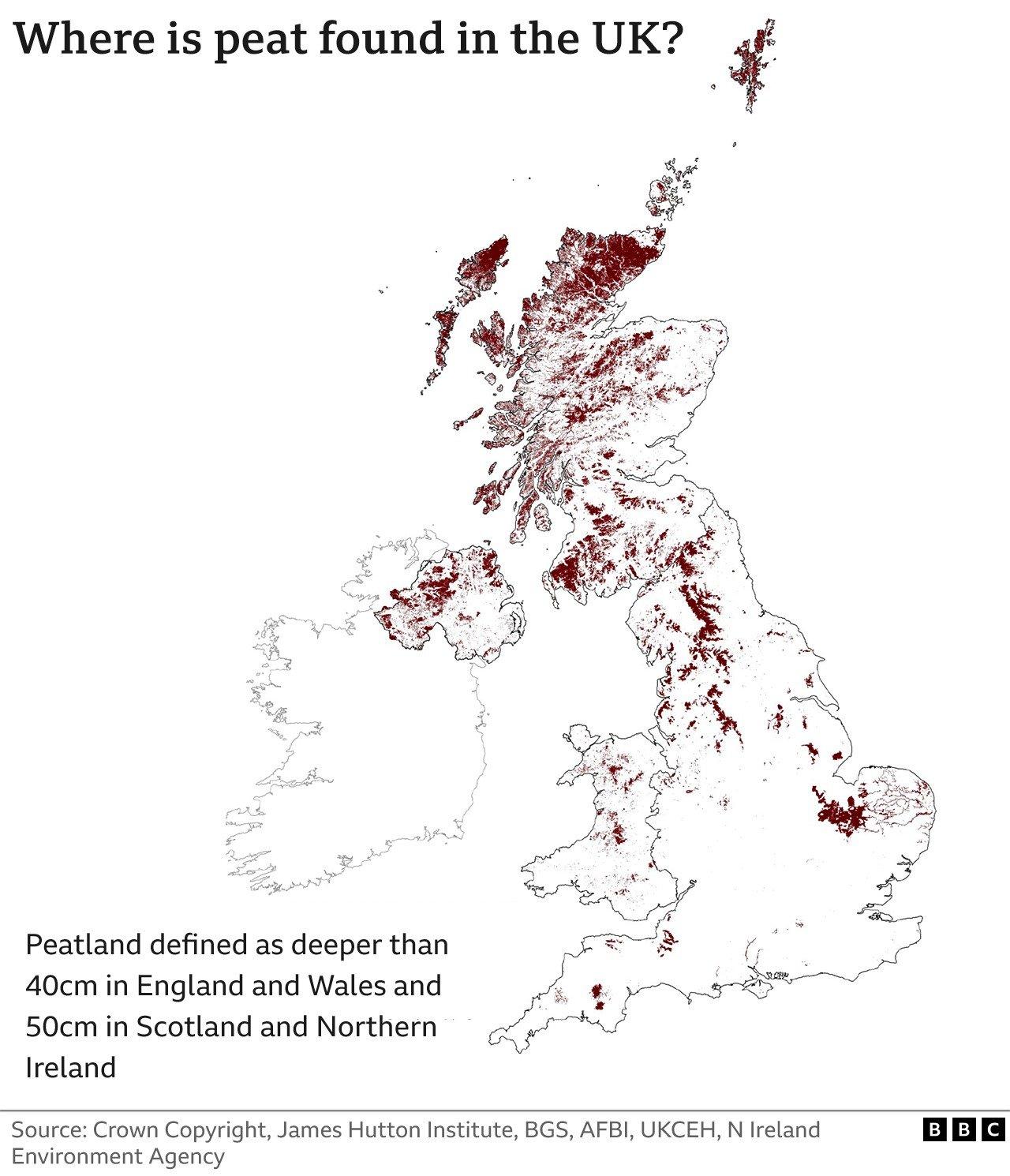

Peatlands cover around 12% of the land in the UK and store an estimated 3 billion tonnes of carbon, equivalent to all the forests in the UK, Germany and France put together.

The government has called England's peatlands its "national rainforests" due to the amount of carbon they store.

But evidence collected by the bird protection charity, the RSPB, and the environmental campaigning organisation Greenpeace, suggests these "rainforests" are still being set on fire illegally in England.

The government told the BBC it has received evidence which claims to show illegal fires and said: "any cases where a breach of consent or regulation is suspected will be investigated".

A traditional practice on shooting estates, burning clears the way for the new green shoots grouse like to eat, but also releases stored carbon into the atmosphere.

Burning on upland peat soils is already restricted to a "season" that runs from 1 October to the 15 April each year.

When the government introduced the new regulations, it said there was "consensus that burning vegetation on blanket bog is damaging to peatland formation and habitat condition."

Blanket bog is a rare ecosystem made up of large areas of deep peat soil.

It said the new rules in England were intended to protect these rare and delicate habitats and to help the UK hit its target to cut emissions to net zero carbon by 2050.

The only exception to the ban would be if a licence has been granted or the land is steep or rocky, but no licences to burn on deep peat were issued during the latest burning season, the government has told the BBC.

The Moorland Association, which represents moorland landowners, says careful burning has been a traditional part of moorland management for more than a century.

It says vegetation typically recovers from well managed burns within three years and that the practice can promote biodiversity and dramatically reduce the risk of wildfires.

Tracking down fires

The RSPB says it has sent the government evidence of 79 fires it believes are in breach of the new regulations. It has created a mobile phone app that allows people to report burns as they see them.

Greenpeace has taken a more high tech approach. It used a NASA satellite to identify "hotspots" - unusually high temperatures - in areas shown on government maps as protected peat moorlands.

Satellite images were then used to confirm fires had taken place.

Sometimes fires were visible in the images at the coordinates identified by NASA.

Your device may not support this visualisation

Where cloud cover made that impossible, the researchers compared before and after pictures to identify burn scars at the location.

The BBC visited two of the estates identified by Greenpeace.

At one, the Bowes estate in the Yorkshire Dales National Park, we found burn scars at and around the coordinates identified by the satellite data.

We tested the peat with the help of a leading expert on UK peatlands, Dr Ben Clutterbuck of Nottingham Trent University, and found it was consistently deeper than 40cm.

We delivered letters to the landowner's registered address with our findings but received no reply.

At another estate the BBC did not find any evidence of burning on deep peat. The landowner appeared to have taken care to only set fire to heather on areas where the peat is less than 40cm deep.

On both estates, we stayed close to a public footpath and took care not to disturb any ground-nesting birds by walking on burnt heather.

Greenpeace visited two other estates. It said there was only evidence of burning on deep peat on one. It says the reason some sites identified as illegal burns turned out to be located on shallow peat is because the government peat map it used as a guide is not definitive.

"Our findings show how important it is that all the locations we have identified are confirmed with site visits", said Emma Howard, a researcher with Greenpeace's investigative journalism unit, Unearthed.

The Moorland Association, which represents the owners of moorland estates, told the BBC it welcomed the government investigation.

It said its members would "cooperate fully and help with any queries". In the meantime, a spokesperson said, they would continue to follow best practice guidelines.

The RSPB, Greenpeace and the Labour Party all call for a blanket ban on burning on all peat

The RSPB and Greenpeace are calling for a blanket ban on burning on all peat.

"Intensive and damaging land management practices such as burning continue to harm and further threaten these vital carbon and nature-rich ecosystems", said Dr Patrick Thompson, a senior policy officer at RSPB UK.

"Why on earth is the government allowing grouse moor owners to turn swathes of national parks and protected sites into charred wasteland for the private gain of a few landowners?" asked Rebecca Newsom, head of politics at Greenpeace UK.

The Labour Party has told the BBC it also wants to see the ban extended to cover all moorland peat.

An estimated 80% of the UK's peatlands are in a damaged and deteriorating condition because of present and past land management activities including drainage, peat cutting, and fire, according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

It estimates that damaged UK peatlands are already releasing almost 3.7 million tonnes of CO2 each year - equivalent to the average emissions of around 660,000 UK households - more than all the households of Edinburgh, Cardiff and Leeds combined.

These emissions are likely to increase with further peatland deterioration as the climate changes, the IUCN says.