Climate change: Russia burns off gas as Europe's energy bills rocket

- Published

- comments

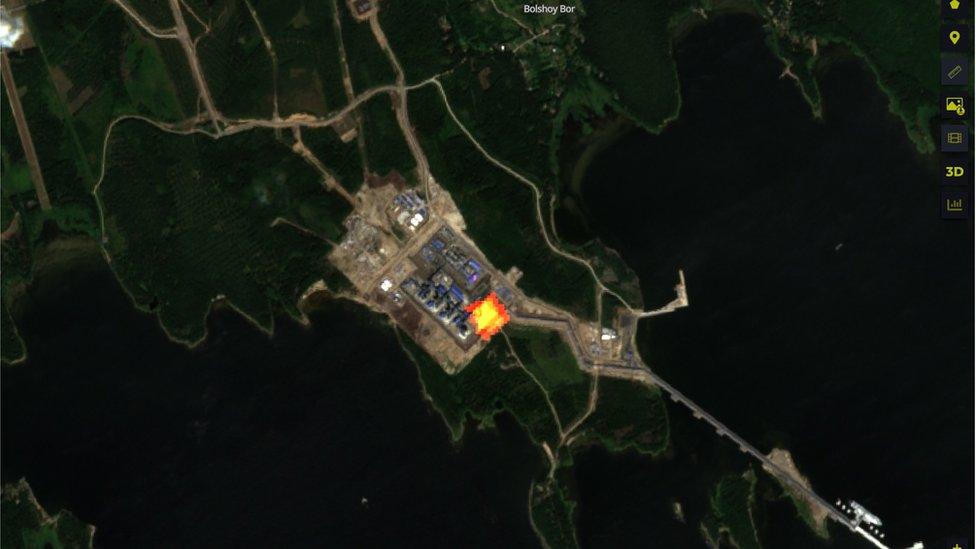

A colourised version of this satellite image captures infrared radiation from the burning of gas at the Portovaya plant

As Europe's energy costs skyrocket, Russia is burning off large amounts of natural gas, according to analysis shared with BBC News.

They say the plant, near the border with Finland, is burning an estimated $10m (£8.4m) worth of gas every day.

Experts say the gas would previously have been exported to Germany.

Germany's ambassador to the UK told BBC News that Russia was burning the gas because "they couldn't sell it elsewhere".

Scientists are concerned about the large volumes of carbon dioxide and soot it is creating, which could exacerbate the melting of Arctic ice.

The analysis by Rystad Energy, external indicates that around 4.34 million cubic metres of gas are being burned by the flare every day.

It is coming from a new liquefied natural gas (LNG) plant at Portovaya, north-west of St Petersburg.

The first signs that something was awry came from Finnish citizens over the nearby border who spotted a large flame on the horizon earlier this summer.

Portovaya is located close to a compressor station at the start of the Nord Stream 1 pipeline which carries gas under the sea to Germany.

Supplies through the pipeline have been curtailed since mid-July, with the Russians blaming technical issues for the restriction. Germany says it was purely a political move following Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

But since June, researchers have noted a significant increase in heat emanating from the facility - thought to be from gas flaring, the burning of natural gas.

While burning off gas is common at processing plants - normally done for technical or safety reasons - the scale of this burn has confounded experts.

"I've never seen an LNG plant flare so much," said Dr Jessica McCarty, an expert on satellite data from Miami University in Ohio.

"Starting around June, we saw this huge peak, and it just didn't go away. It's stayed very anomalously high."

Miguel Berger, the German ambassador to the UK, told BBC News that European efforts to reduce reliance on Russian gas were "having a strong effect on the Russian economy".

"They don't have other places where they can sell their gas, so they have to burn it," he suggested.

This photo was taken by Finnish citizen Ari Laine on 24 July at a distance of around 23 miles (38km) from the Portovaya facility

Mark Davis is the CEO of Capterio, external, a company that is involved in finding solutions to gas flaring.

He says the flaring is not accidental and is more likely a deliberate decision made for operational reasons.

"Operators often are very hesitant to actually shut down facilities for fear that they may be technically difficult or costly to start up again, and it's probably the case here," he told BBC News.

Others believe that there could be technical challenges in dealing with the large volumes of gas that were being supplied to the Nord Stream 1 pipeline.

Russian energy company Gazprom may have intended to use that gas to make LNG at the new plant, but may have had problems handling it and the safest option is to flare it off.

It could also be the result of Europe's trade embargo with Russia in response to the invasion of Ukraine.

"This kind of long-term flaring may mean that they are missing some equipment," said Esa Vakkilainen, an energy engineering professor from Finland's LUT University.

"So, because of the trade embargo with Russia, they are not able to make the high-quality valves needed in oil and gas processing. So maybe there are some valves broken and they can't get them replaced."

Gazprom - Russia's state-controlled energy giant which owns the plant - has not responded to requests for comment on the flaring.

The financial and environmental costs mount each day the flare continues to burn, say scientists.

"While the exact reasons for the flaring are unknown, the volumes, emissions and location of the flare are a visible reminder of Russia's dominance in Europe's energy markets," said Sindre Knutsson from Rystad Energy.

"There could not be a clearer signal - Russia can bring energy prices down tomorrow. This is gas that would otherwise have been exported via Nord Stream 1 or alternatives."

Energy prices around the world rose sharply as Covid lockdowns were lifted and economies returned to normal. Many places of work, industry and leisure were all suddenly in need of more energy at the same time, putting unprecedented pressures on suppliers.

Prices increased again in February this year, after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. European governments looked for ways to import less energy from Russia, which had previously supplied 40% of the gas used in the EU.

Prices for alternative sources of gas went up as a result, and some EU nations - like Germany and Spain - are now bringing in energy-saving measures.

The smoke and orange light from the gas flare at Portovaya is seen on the left of this image captured by holidaymaker Elmeri Rasi

The environmental impacts of the burning are worrying scientists.

According to researchers, flaring is far better than simply venting the methane which is the key ingredient in the gas, and is a very powerful climate warming agent.

Russia has a track record of burning off gas - according to the World Bank, it is the number one country, external when it comes to the volume of flaring.

But as well as releasing about 9,000 tonnes of CO2 equivalent every day from this flare, the burning causes other significant issues.

Black carbon is the name given to the sooty particles that are produced through the incomplete burning of fuels like natural gas.

"Of particular concern with flaring at Arctic latitudes is the transport of emitted black carbon northward where it deposits on snow and ice and significantly accelerates melting," said Prof Matthew Johnson, from Carleton University in Canada.

"Some highly cited estimates already put flaring as the dominant source of black carbon deposition in the Arctic and any increases in flaring in this region are especially unwelcome."

Follow Matt on Twitter @mattmcgrathbbc, external.

Related topics

- Published26 January 2023

- Published23 February 2024