Earliest evidence of amputation found in Indonesia cave

- Published

The earliest evidence ever of surgical amputation has been discovered in an Indonesian cave.

Researchers found the buried 31,000-year-old body of a young person that shows evidence of leg amputation.

The find pushes back the origin of this complicated surgery by more than 24,000 years.

After the procedure the person was cared for by their ancient community for years until their death, archaeologists say.

Dr Melandri Vlok, who examined the body, said it was "quite clear" surgery had been carried out.

A detailed examination of the ancient body, details of which are published in the journal Nature, external, revealed that the operation took place when the person was a child. Growth and healing of their leg bone suggests they recovered and lived for another six to nine years, probably dying in their late teens or early twenties.

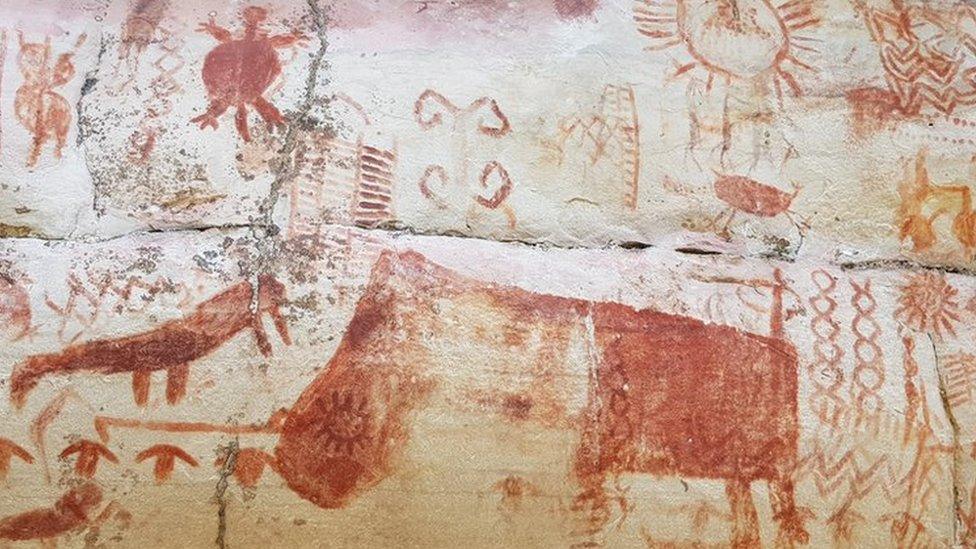

The grave itself was excavated in a cave called Liang Tebo, in East Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo, a place that has some of the world's earliest rock art.

One of the three researchers who found and excavated the grave, Dr Tim Maloney from the Griffith University in Australia, said he was simultaneously "excited and terrified" to reveal the ancient bones.

As well as the left foot being absent, the leg bones show signs of healing

"We very carefully brushed away the deposits and recorded the lower half of the remains. We could see that the left foot was absent, but also that the remaining bone fragments were unusual," he told BBC News.

"So we were excited at the range of possibilities, including surgery, that had caused this."

The excavation team subsequently asked Dr Vlok, who is based at the University of Sydney, to examine the remains. "With a discovery like this", she said, "it's a mixture of excitement and sorrow, because this happened to a person.

"This person - a child - experienced so much pain, even if it was 31,000 years ago."

Dr Maloney explained that, because this person showed signs of having been cared through their recovery and for the rest of their life, the archaeologists are confident that this was an operation, rather than any kind of punishment or ritual.

"To allow them to live in this mountainous terrain, it's highly likely that the rest of their community invested in their care," he explained.

Durham University archaeologist Prof Charlotte Robertson, who was not involved in the discovery but reviewed the findings, added that they challenged the view that medicine and surgery came late in human history.

An artist's impression of the person during their life 31,000 years ago

"It shows us that caring is an innate part of being human," she told the BBC. "We can't underestimate our ancestors."

Amputations, she pointed out, require a comprehensive knowledge of human anatomy and surgical hygiene, and considerable technical skill.

"Nowadays, you think about amputation in western context, it's a very safe operation. The person is given anaesthesia, sterile procedures are used, there is control of bleeding and pain management.

"Then you've got 31,000 years ago, someone is performing an amputation on this person and it's successful."

Dr Maloney and his colleagues are now working to investigate what kind of stone surgical tools could have been used at that time.

Follow Victoria on Twitter, external

Related topics

- Published5 May 2021

- Published3 December 2020

- Published20 January 2020