Satellites now get full-year view of Arctic sea-ice

- Published

In summer months, up to 30% of the sea-ice can be covered in meltponds

Satellites can now measure the thickness of sea-ice covering the Arctic Ocean all year round.

Traditionally, spacecraft have struggled to determine the full state of the floes in summer months because the presence of surface meltwater has befuddled their instruments.

But by using new "deep learning" techniques, scientists have pushed past this limitation to get reliable observations across all seasons.

The breakthrough has wide implications.

Apart from the obvious advantage to ships, which need to know those parts of the Arctic that will be safe to navigate, there are significant benefits to climate and weather forecasting.

At the moment, there is considerable variation in the projections for when the polar ocean might be totally free of ice in an ever warmer world.

Having an improved insight into the melting processes in those key months when floes are being reduced, in area and thickness, ought now to sharpen the output from computer models.

"Despite excellent efforts by many researchers, these climate models' predictions of when we'll see the first fully ice-free Arctic Ocean in summer - they vary by 30-plus years," Dr Jack Landy, from UiT The Arctic University of Norway, told BBC News.

"We need to tighten those predictions so we're a lot more confident about what's going to happen and when - and how the climate feedbacks will accelerate as a consequence."

Prof Julienne Stroeve: "This will help us nail down when that first ice-free summer may happen"

The extent of Arctic sea-ice cover has been in decline for the entire period that satellites have been monitoring it, which is more than 40 years - a reduction running at an average rate of 13% per decade, external.

But it's only really since 2011 that spacecraft have been able to consistently measure its thickness - and thickness (or more properly, volume) is the true measure of the floes' health.

That's because the extent of sea-ice cover is heavily dependent on whether the winds have spread out the floes or pushed them together.

To measure thickness, scientists use satellite altimeters.

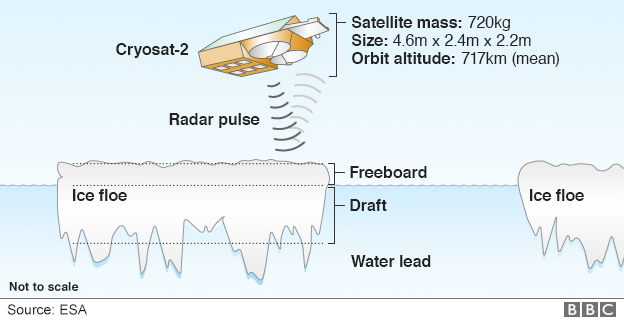

The European Space Agency's (Esa) pioneering Cryosat-2 mission carries a radar to measure the difference in height between the top of the marine ice and the top of the water in the cracks, or leads, that separate the floes.

From this difference, scientists can then, with a relatively simple calculation, work out the thickness of the ice.

The approach works well in winter months, but in summer, when the snows on top of the ice, and the ice itself, start to melt, pooling water effectively dazzles the radar. Scientists can't be sure if the echo signal that returns to Cryosat is coming from the open ocean or from the surface of a meltpond sitting on the ice.

May through to September - the key melt season - has been a blind period for the spacecraft.

To solve the problem, researchers used an artificial intelligence (AI) technique in which an algorithm was able to learn and identify reliable observations from a vast library of synthetic radar signals.

Arctic ice helps to cool Earth by reflecting the Sun's energy - up to 80% - straight back out into space

Prof Julienne Stroeve, from University College London (UCL), explained: "We simulated what would be the echo shapes that we would get for different ice surface types - whether they had meltponds; whether it was flooded ice; or ice of different roughnesses; or simply leads. We created this huge database of physically based estimates of what the radar return should look like, and then we matched those to the individual radar pulses from the instrument to find echoes that matched the best."

Esa has kept in its data archives all the Cryosat May-to-September measurements, even though for the past decade they've been of next to no use. But now, thanks to this new approach, Dr Landy's team has been able to go back through the records to recover full-year ice thickness measurements for the entire time the satellite has been operational.

Dr Rachel Tilling worked extensively with Cryosat data before transferring her studies to the US space agency's recently launched Icesat-2 laser altimeter mission.

She applauded the innovation.

"Summer is when sea-ice extent in the Arctic is seeing its most rapid decline, and having this extra dimension will help us understand more about how the ice pack is changing," the Nasa scientist told BBC News.

"Icesat-2 has its own unique difficulties in summer but we're lucky that its photon-counting technology means we can still measure the height of sea-ice, water and melt ponds year-round.

"Having said that, Cryosat-2 will always be my first love so I'm really excited to see it being used in this novel way."

The volume of sea-ice has halved across the Arctic since the late 1970s

A chief beneficiary of the new thickness measurements would be Inuit populations in the Arctic, said Dr Michel Tsamados, also from UCL.

"[They] have identified sea-ice roughness and slush (melted snow and ice) as a key impediment for safe travel on the ice with the changing climate already negatively affecting these characteristics and causing increased travel accidents and search-and-rescues," he explained.

"Both are related to the thickness of the ice. Therefore, measuring throughout the full year the sea-ice thickness from space from Cryosat-2 but also Icesat-2 and other satellite sensors will eventually help provide better maps to the Inuit populations for safe travel over this rapidly changing terrain."

Dr Landy and colleague have published their new Cryosat approach in the journal Nature, external.

How to measure sea-ice thickness

Cryosat's radar has the resolution to see the Arctic's "floes" and "leads"

Some 8/9ths of the ice tends to sit below the waterline - the draft

The radar senses the height of the freeboard - the ice above the waterline

Knowing this 1/9th figure allows Cryosat to work out sea-ice thickness

The thickness multiplied by the area of ice cover produces a volume

Icesat-2 does exactly the same as Cryosat but with a laser instrument

The biggest uncertainty for both is the covering of snow on the ice