Winchcombe meteorite bolsters Earth water theory

- Published

The Winchcombe meteorite broke off an asteroid between Mars and Jupiter

A meteorite that crashed on the Gloucestershire town of Winchcombe last year contained water that was a near-perfect match for that on Earth.

This bolsters the idea rocks from space brought key chemical components, including water, to the planet early in its history, billions of years ago.

The meteorite is regarded as the most important recovered in the UK.

Scientists publishing their first detailed analysis, external say it has yielded fascinating insights.

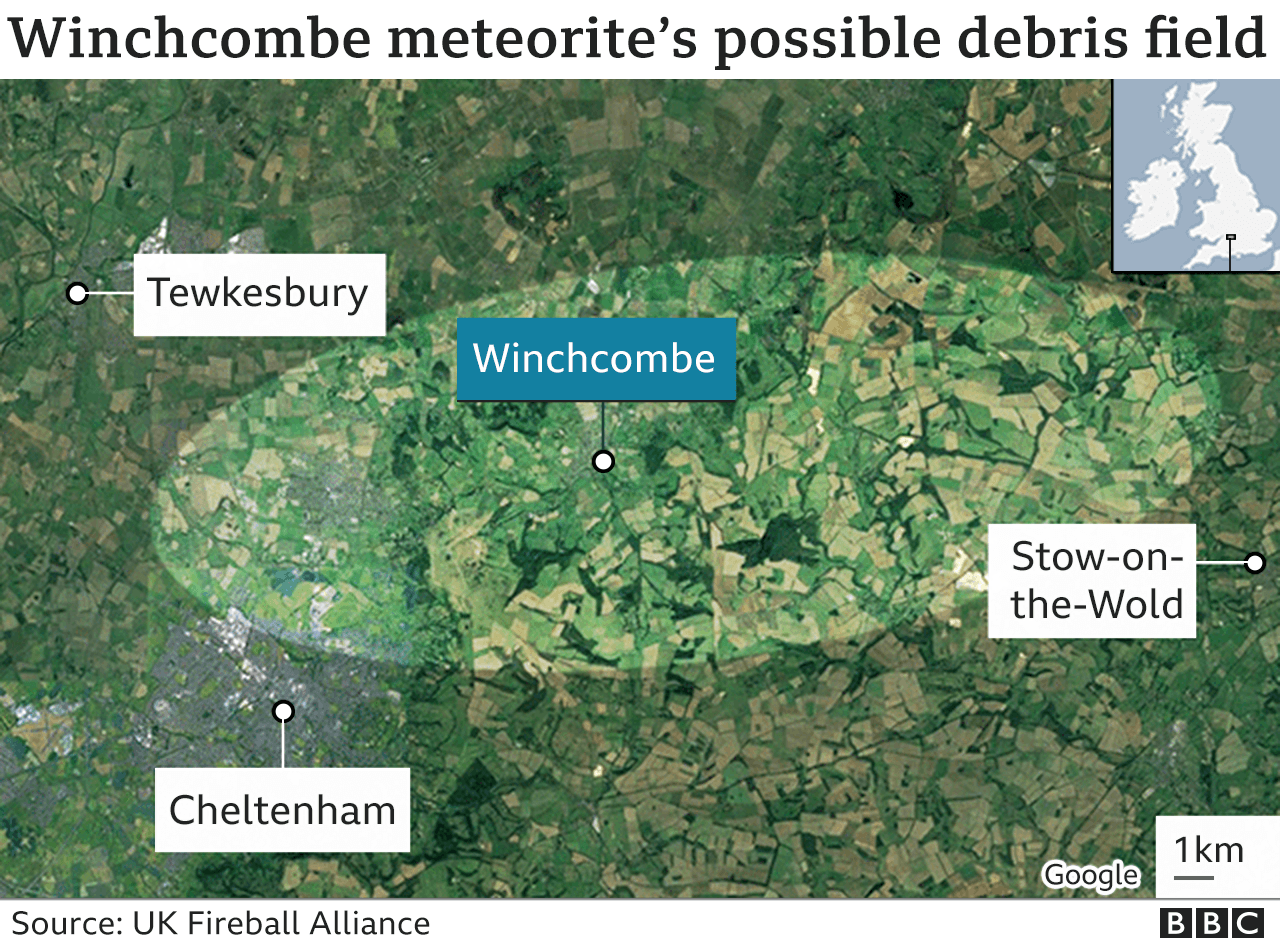

More than 500g (1lb) of blackened debris was picked up from people's gardens and driveways and local fields, after a giant fireball lit up the night sky.

The crumbly remains were carefully catalogued at London's Natural History Museum (NHM) and then loaned to teams across Europe to investigate.

Water accounted for up to 11% of the meteorite's weight - and it contained a very similar ratio of different types of hydrogen atoms to the water on Earth.

Some scientists say the young Earth was so hot it would have driven off much of its volatile content, including water.

For the Earth to have so much today - 70% of its surface is covered by ocean - suggests there must have been a later addition.

Some say this could have come from a bombardment of icy comets - but their chemistry is not a great match.

Carbonaceous chondrites, however - meteorites such as the Winchcombe one - most certainly are.

And the fact it was recovered less than 12 hours after crashing means it had absorbed very little earthly water, or indeed any contaminants.

"All other meteorites have been compromised in some way by the terrestrial environment," co-first author Dr Ashley King, from the NHM, told BBC News.

"But Winchcombe is different because of the speed with which it was picked up.

"This means when we measure it, we know the composition we're looking at takes us all the way back to the composition at the beginning of the Solar System, 4.6 billion years ago.

"Bar fetching rock samples back from an asteroid with a spacecraft, we could not have a more pristine specimen."

Precise trajectory

Scientists examining the meteorite's carbon- and nitrogen-bearing organic compounds, including its amino acids, had a similarly clean picture.

This is the type of chemistry that could have been a feedstock for biology to begin on the early Earth.

The new analysis also confirms the meteorite's origin.

Camera footage of the fireball has allowed researchers to work out a very precise trajectory.

Calculating backwards, this indicates the meteorite came from the outer asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

Winchcombe material recently sold at auction for more than 120 times the value of its weight in gold

Further investigations reveal it was knocked off the top few metres of a parent asteroid, presumably in some collision.

It then took only 200,000 to 300,000 years to arrive on Earth, the number of particular atoms, such as neon, created in the meteorite material through the constant irradiation from high-speed space particles, or cosmic rays, reveals.

"0.2-0.3 million years sounds like quite a long time - but from a geological perspective, it's actually very quick," Dr Helena Bates, from the NHM, said.

"Carbonaceous chondrites have to get here quickly or they won't survive, because they're so crumbly, so friable, they'll just break apart."

'More secrets'

The scientists first analysis, in this week's edition of the Science Advances journal, external, is just an overview of Winchcombe's properties.

A dozen more papers on specialist topics are due to come out shortly in an issue of the Meteoritics & Planetary Science journal.

And even they will not be the last word.

"Researchers will continue to work on this specimen for years to come, unlocking more secrets into the origins of our Solar System," co-first author Dr Luke Daly, from the University of Glasgow, said.