Superbug fight 'needs farmers to reduce antibiotic use'

- Published

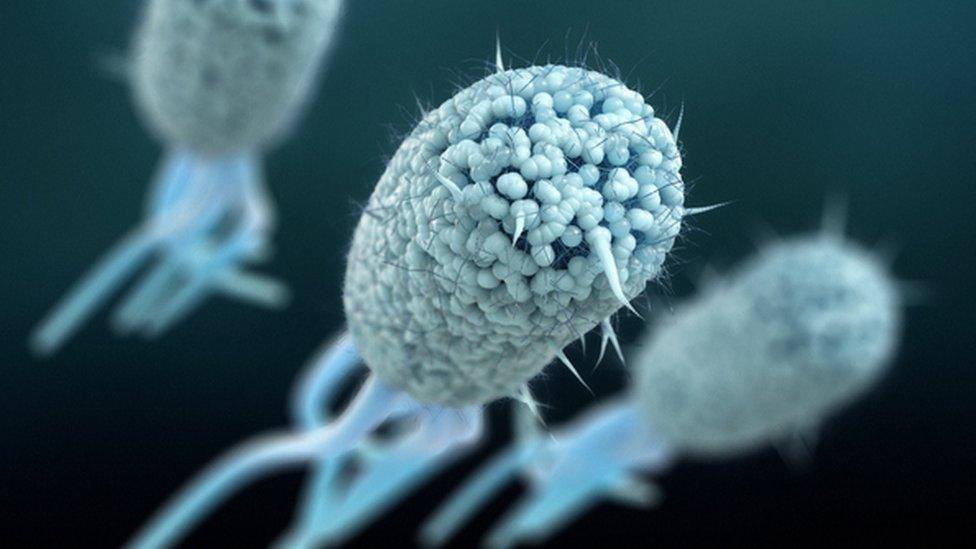

E-coli bacteria can develop a resistance to the drugs used to treat them.

Health and animal welfare campaigners concerned about the spread of superbugs in humans are calling for a ban on the overuse of antibiotics in farm animals.

They say routinely using antibiotics in livestock can lead to bacteria becoming resistant and such 'superbugs' could spread to humans.

Sample tests they carried out in rivers near farms, in slurry and in chicken litter found resistant bacteria.

The government said it is considering new restrictions on antibiotic use.

A spokesperson from the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra) said: "We do not support routine preventative use of antibiotics in animals - they should not compensate for poor husbandry practices and we will continue to look into strengthening legislation in this area."

The National Farmers Union said UK farming was "a leader when it comes to the responsible use of antibiotics".

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has been described by the World Health Organisation as "one of the biggest threats to global health, food security, and development today.", external

The overuse of antibiotics, in both human medicine and agriculture, has seen them become less effective and led to the rise of 'superbugs' - strains of bacteria that can no longer be treated by certain drugs.

The latest data published by the UK Health Security Agency shows that the estimated total number of serious antibiotic resistant infections in England rose by 2.2% in 2021 compared to 2020, from 52,842 to 53,985.

Researchers for the Alliance to Save our Antibiotics and World Animal Protection carried out tests for superbugs in rivers alongside a dozen intensive and higher-welfare pig and poultry farms in Warwickshire, Herefordshire, Devon, Norfolk and the Wye Valley and in the slurry from four intensive dairy farms and in one chicken litter sample.

Environmental impacts

They said they found a range of antibiotic-resistant genes and resistant strains of bacteria, Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus).

They said higher levels of at least one type of resistance were found downstream of five of out eight intensive farms. None of the four higher welfare outdoor pig or chicken farms tested had higher levels of any type of resistance downstream than was found upstream, according to the report.

"Overall, our findings suggest that factory farms are likely to be discharging resistance genes and superbugs into public waterways," concluded the report, which was drawn up with Fera Science, external and the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, external.

Intensive 'factory' farming methods have been blamed for contributing to the rise in AMR, with claims that a high number of animals kept closely together can be a breeding ground for disease and can lead to antibiotics being given to whole herds or flocks simply to keep illness at bay.

Cóilín Nunan, scientific adviser to the Alliance to Save Our Antibiotics, said that higher-welfare farming methods were needed to keep the risk of illness and antibiotic use down.

"Most antibiotics taken by people or animals are excreted, along with antibiotic-resistant bacteria. When manure or slurry is spread on land, this increases the number of resistant bacteria in soils and water," he said.

"The best way to reduce farming's impact is to make large cuts to antibiotic use, and this means keeping animals in healthier conditions so they rarely need medication."

Professor Isabelle Durance, director of the Cardiff Water Research Institute, who was not involved in the study, told the BBC it was accepted that faecal matter entering water bodies can carry with it drug-resistant bacteria and genes, external, and that could come from farming.

"We know that with faecal material from agricultural production, there is an amount that enters wastewater. You can have perfectly healthy chickens with bacteria that have antimicrobial resistance. As soon as there is faecal material in water bodies there will be anti-microbial resistant bacteria," she explained.

But she warned it was "extremely difficult" to link the bacteria in rivers to a specific source.

Peter Greig says his farms only use antibiotics when absolutely necessary

Peter Greig, the co-founder of Pipers Farm, oversees 45 higher-welfare outdoor farms across Somerset, Devon, Cornwall, Wales and East Anglia which, he says, only use antibiotics when sick animals are in need and not as a routine preventative measure.

Mr Greig said he was not surprised by the report's findings: "It's a no-brainer. The excreta which comes out of an industrial pig or poultry environment is then spread so that it feeds into the groundwater and into the rivers. That causes a major disruption to the balance of nature."

In January, the EU banned all routine farm antibiotic use and all preventative antibiotic, external treatments of groups of animals in order to tackle the overuse, and inappropriate use, of the medicines.

The government had supported a ban in 2018 but has yet to carry out the public consultation it said it would.

Defra said proposed changes to existing regulations on antibiotic use on farms would be put out for public consultation "in due course".

Meanwhile, the latest annual UK Veterinary Antibiotic Resistance and Sales Surveillance (UK-VARSS) report, external, published earlier this month, showed sales of antibiotics for use in livestock had reduced by 55% since 2014.

Cat McLaughlin, of The Responsible Use of Medicines in Agriculture (RUMA) Alliance, said livestock farmers were continuing to "make positive progress on antibiotic use reduction targets".

But she added: "We must remember that antibiotics are important tools that the veterinary sector needs at its disposal to protect animal health and welfare against disease challenges.'

- Published12 April 2022

- Published15 February 2022

- Published20 January 2022

- Published5 January 2022

- Published17 November 2021