SpaceX Starship: Elon Musk's firm postpones launch of biggest rocket ever

- Published

- comments

Watch: The moment the launch of Starship was halted for the day

An attempt to launch the most powerful ever rocket into space has been postponed for at least 48 hours.

The vehicle, known as Starship, has been built by entrepreneur Elon Musk's SpaceX company.

The uncrewed mission on Monday was called off minutes before the planned launch from Boca Chica, Texas.

The problem appears to have been caused by a frozen "pressurant valve", Musk tweeted. But SpaceX could try to launch again later this week.

Starship stands nearly 120m (400ft) high and is designed to have almost double the thrust of any previous rocket.

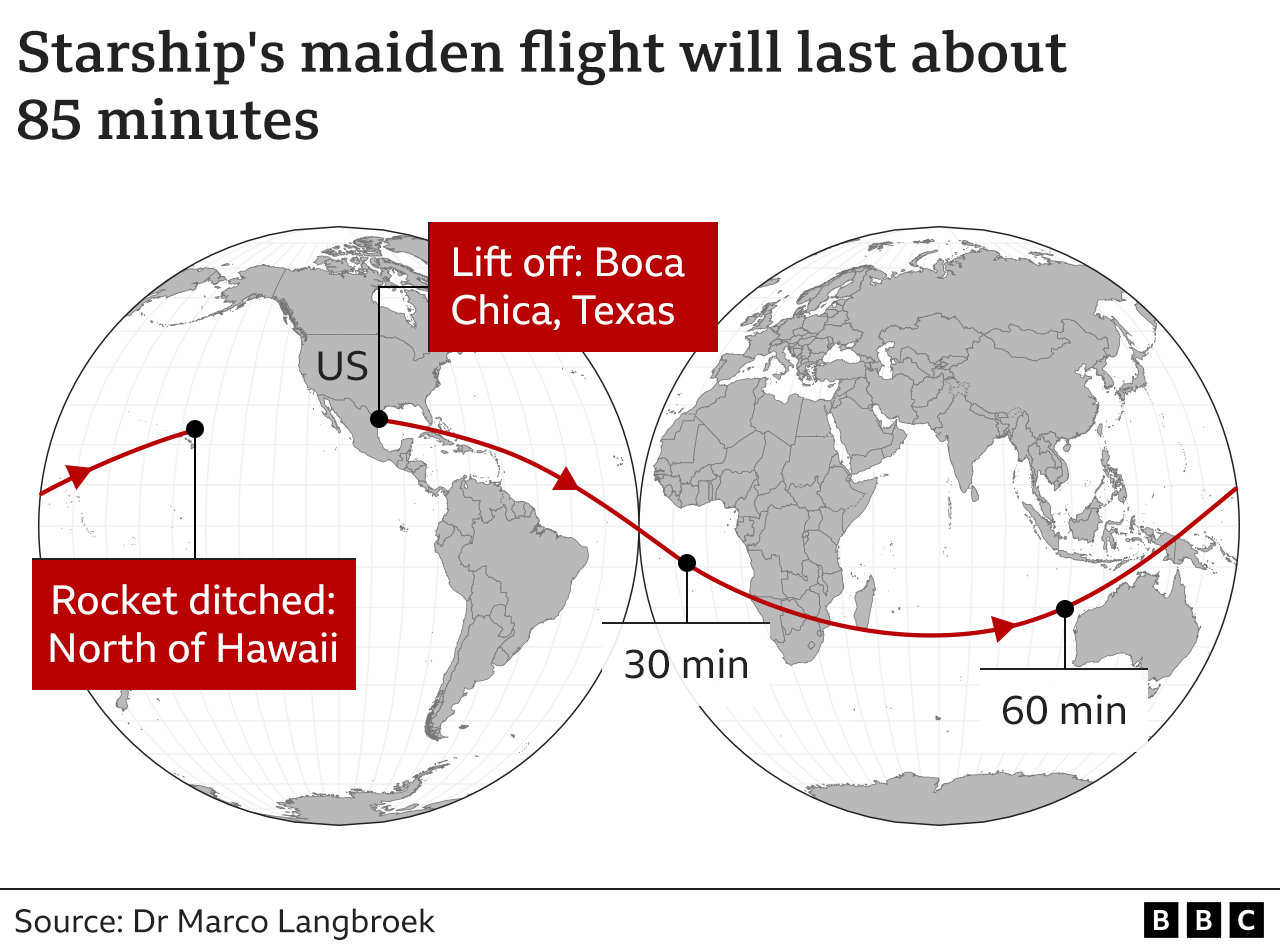

The aim is to send the upper-stage of the vehicle eastward, to complete almost one circuit of the globe.

Before the launch was postponed, Mr Musk had appealed for everyone to temper their expectations. It's not uncommon for a rocket to experience some kind of failure on its initial outing.

"It's the first launch of a very complicated, gigantic rocket, so it might not launch. We're going to be very careful, and if we see anything that gives us concern, we will postpone the launch," he had told a Twitter Spaces event.

Thousands of spectators filled coastal locations on the Gulf of Mexico to witness the event.

Elon Musk is hoping to completely upend the rocket business with Starship.

It's designed to be fully and rapidly reusable. He envisages flying people and satellites to orbit multiple times a day in the same way a jet airliner might criss-cross the Atlantic.

Indeed, he believes the vehicle could usher in an era of interplanetary travel for ordinary humans.

The booster was held on the ground when its engines were ignited for a "static fire" test

The top segment of Starship has been tested previously on short hops, but this would have been the first time it would go up with its lower-stage.

This mammoth booster, suitably called Super Heavy, was fired while clamped to its launch mount in February. However, the engines on that occasion were throttled back to half their capability.

If things go to plan for another launch this week, SpaceX will aim for 90% thrust, meaning the stage should deliver something close to 70 meganewtons. This is equivalent to the force needed to propel almost 100 Concorde supersonic airliners at take off.

Assuming everything proceeds as planned, Starship will rise up and head down range across the Gulf, the 33 engines on the bottom of the methane-fuelled booster burning for two minutes and 49 seconds.

At that point, the two halves of the rocket will separate, and the top section, the ship, will push on with its own engines for a further six minutes and 23 seconds.

By this time, it should be travelling over the Caribbean and cruising through space more than 100km (62 miles) above the planet's surface.

SpaceX wants the Super Heavy booster to try to fly back to near the Texan coast and come down vertically, to hover just above the Gulf's waters. It will then be allowed to topple over and sink.

The ship is expected to re-enter the Earth's atmosphere after almost a full revolution of the Earth, coming down in the Pacific just north of the Hawaiian islands. It's been given protective tiling to cope with the immense heating it will experience during the descent.

A bellyflop into the ocean is timed to occur roughly an hour and a half after lift-off.

In the longer term, SpaceX expects both the booster and the ship to be making controlled landings so they can be refuelled and relaunched.

The company has been experimenting at Boca Chica with different approaches to building the steel stages.

There are various models waiting their turn to take flight.

One of the most interested spectators on Monday will have been the US space agency, Nasa.

It is giving SpaceX almost $3bn to develop a variant of Starship that is planned to land astronauts on the Moon.

Garrett Reisman, a professor of astronautical engineering at the University of Southern California, says Mr Musk has the ambition to go even deeper into the Solar System.

"He sees Starship as potentially another giant paradigm shift, an incredible increase in capability - the capability to truly bring people on large scale to Mars," the SpaceX advisor and former astronaut told BBC News.

"There's a lot of potential benefit, but there's also a lot of potential risk because this is very difficult. Nobody's built a rocket anywhere near this big - twice as big as the next nearest thing."