Royal Society: Four incredible objects that made science history

- Published

Fossil hunters on the south coast of England sent pictures of their finds to scientists

One of the first scientific findings signed by a woman is now online for the public to see for the first time.

Martha Gerrish's descriptions of the stars in 1734 joins discoveries by Isaac Newton, Victorian fossil hunters and pioneer photographers.

The documents have been digitised by the scientific institution the Royal Society in London.

It hopes it will lead to more discoveries as researchers use the archive.

Around 250,000 documents can now be viewed online, covering everything from climate observations, the history of colour, how to conduct electricity, and animals.

You can access the online archive here. , externalWe have picked out some of the highlights:

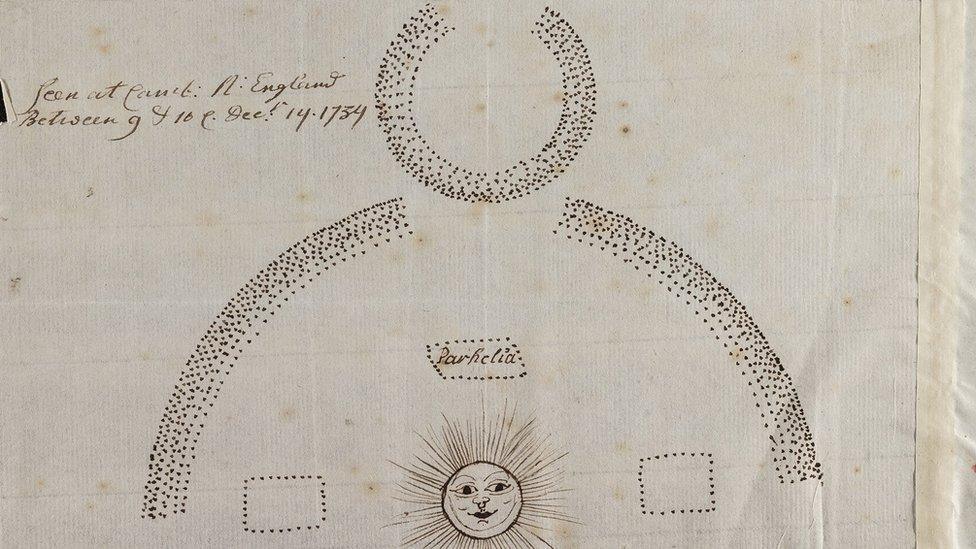

First letter signed by a woman

In 1734 a woman living in New England called Martha Gerrish wrote to the Royal Society that she had spotted a rare astronomical sight called a Parhelion or 'sun dog' - an optical phenomenon that appears in the sky as two halos beside the sun.

It is the first letter in the archives of the society's journal - called Philosophical Transactions - known to be sent by a woman in her own name. Most women at the time had limited access to formal education and would not be considered intellectual equals to men.

A drawing of a sundog by Martha Gerrish who signed the letter to the Royal Society with her own name

Ms Gerrish acknowledges this imbalance in her letter when she wrote: "If this came from a masculine hand, I believe it would be an acceptable present to the Royal Society."

The letter demonstrates that women have contributed to science for centuries even when their work was not public, explains Royal Society historian Louisiane Ferlier.

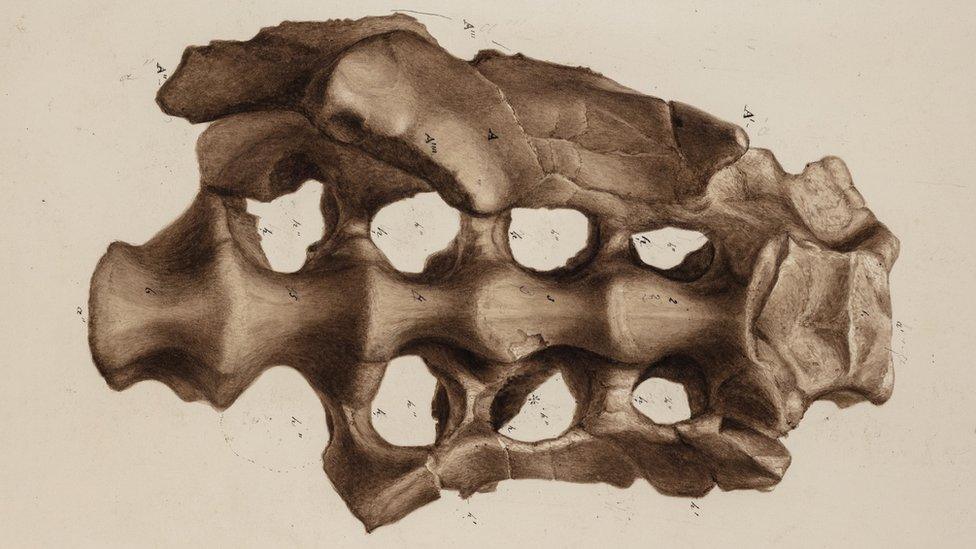

Victorian dinosaurs

Dinosaur hunter Gideon Mantell sent in detailed drawings from discoveries in 1849 he made of dinosaur fossils on the Jurassic coast, in southern England.

Some of the drawings were in fact made by his wife, explains Royal Society librarian Keith Moore, and were essential in showing other scientists what had been discovered before photography had been invented.

Fossil hunters drew their dinosaur finds and sent to scientists for study

Drawings of the dinosaur fossils were crucial to collectors but also to anatomists who were trying to work out how the bones fitted together to form an animal, Mr Moore adds.

"You've got a bunch of bones here. How are they put together? These days we kind of know what a dinosaur looks like, but when you're starting from absolute scratch, these drawings were really helpful," he explains.

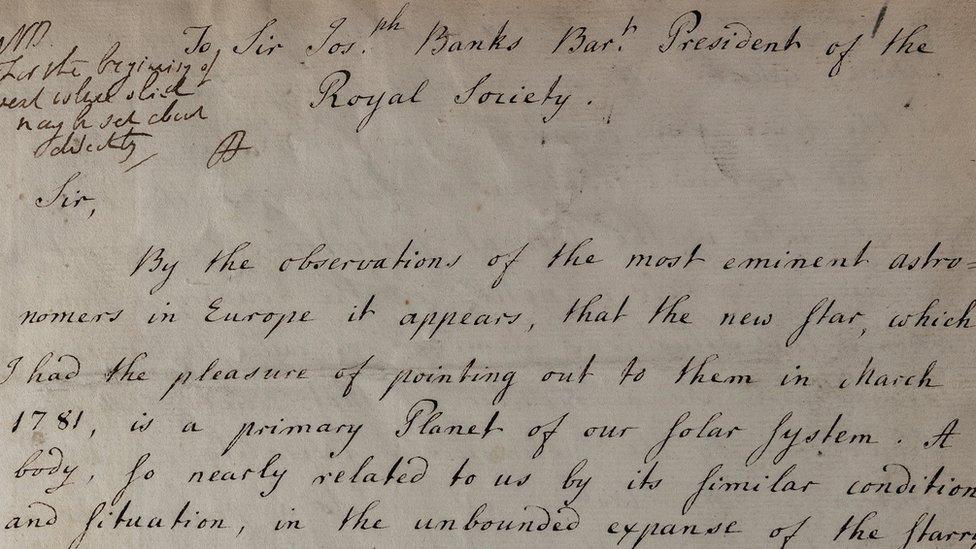

Discovery of Uranus

Have a look at the original letter written by the scientist who discovered the planet Uranus.

William Herschel wrote to the society in 1782 to say he had spotted a new "primary planet of our solar system".

The letter from William Herschel explaining that he had discovered a new planet

It was a shocking discovery at the time, Mr Moore says, because scientists thought they understood what was in the skies.

But William Herschel was using a powerful new telescope and "suddenly he found something new, which was the first planet discovered in modern history".

But if Herschel had had his way, we would be calling the planet Uranus something totally different. His idea was to name it "Georgium Sidus" - after the sitting King George III.

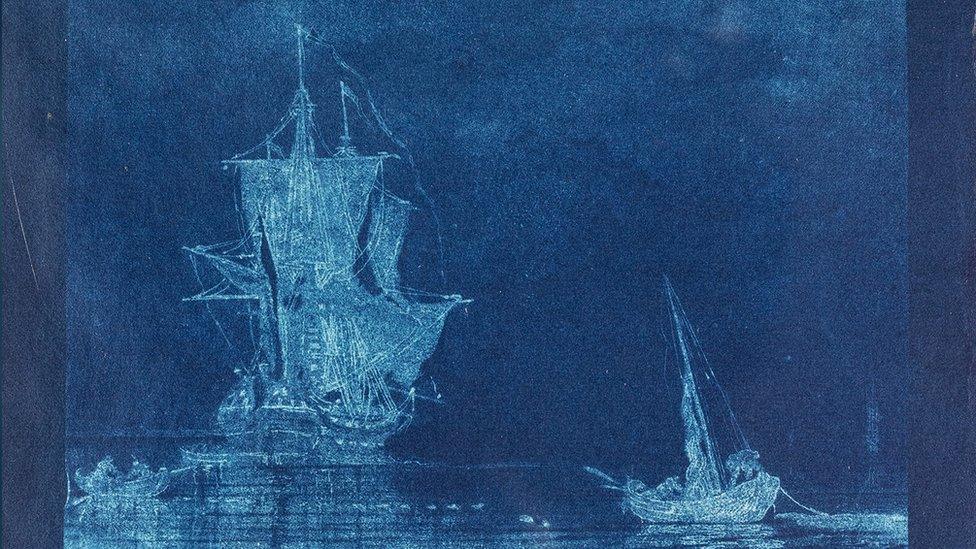

Early photography experiments

Long before smartphones and digital cameras were everywhere, inventors in the 1830s and 1840s were experimenting with a new idea.

Some of the first attempts to capture images were sent to the Royal Society.

An early experiment with cyanotype photography from the 1830s

One innovator, William Henry Fox Talbot, wrote in 1839 that he thought he had discovered something that might have "many useful and important applications".

His letters also reveal how inventions can sometimes come about through failure, explains librarian Mr Moore.

Frustrated by his poor drawing abilities, Mr Talbot turned to trying to invent a new way to capture pictures.

As well as these four finds, the Royal Society - one of the world's leading scientific organisations - has thousands of other objects collected since it was founded in 1660.

Ground-breaking scientists including Benjamin Franklin, Edmund Halley and Isaac Newton sent their research findings to the society's journal.

But ordinary people could also submit their ideas and discoveries in letters and pictures. One letter in 1790 from a French cloth-maker included a piece of silk that he said demonstrated he had discovered how to make the "pinkest ever pink dye".

Making the history of science more accessible to the public is "essential", says Ms Ferlier, who helped to digitise the archive.

"It shows how science has evolved and grew into a discipline with checks and balances that we can trust today," she explains.