Meteosat-12: Europe's new weather satellite takes first photos

- Published

WATCH: Meteosat-12 takes a picture of the weather systems below it every 10 minutes

The first images from Europe's new weather satellite, Meteosat-12, have just been released.

The spacecraft, which sits 36,000km above the equator, was launched in December and is currently in a testing phase that will last most of this year.

When Meteosat-12's data is finally released to meteorological agencies, it's expected to bring about a step-change in forecasting skill.

Warnings of imminent, hazardous conditions should improve greatly.

This is something called "nowcasting" - the ability to say with greater confidence that violent winds, lightning, hail or heavy downpours are about to strike a particular area.

Meteosat-12 should help forecasters identify those places about to experience extreme conditions

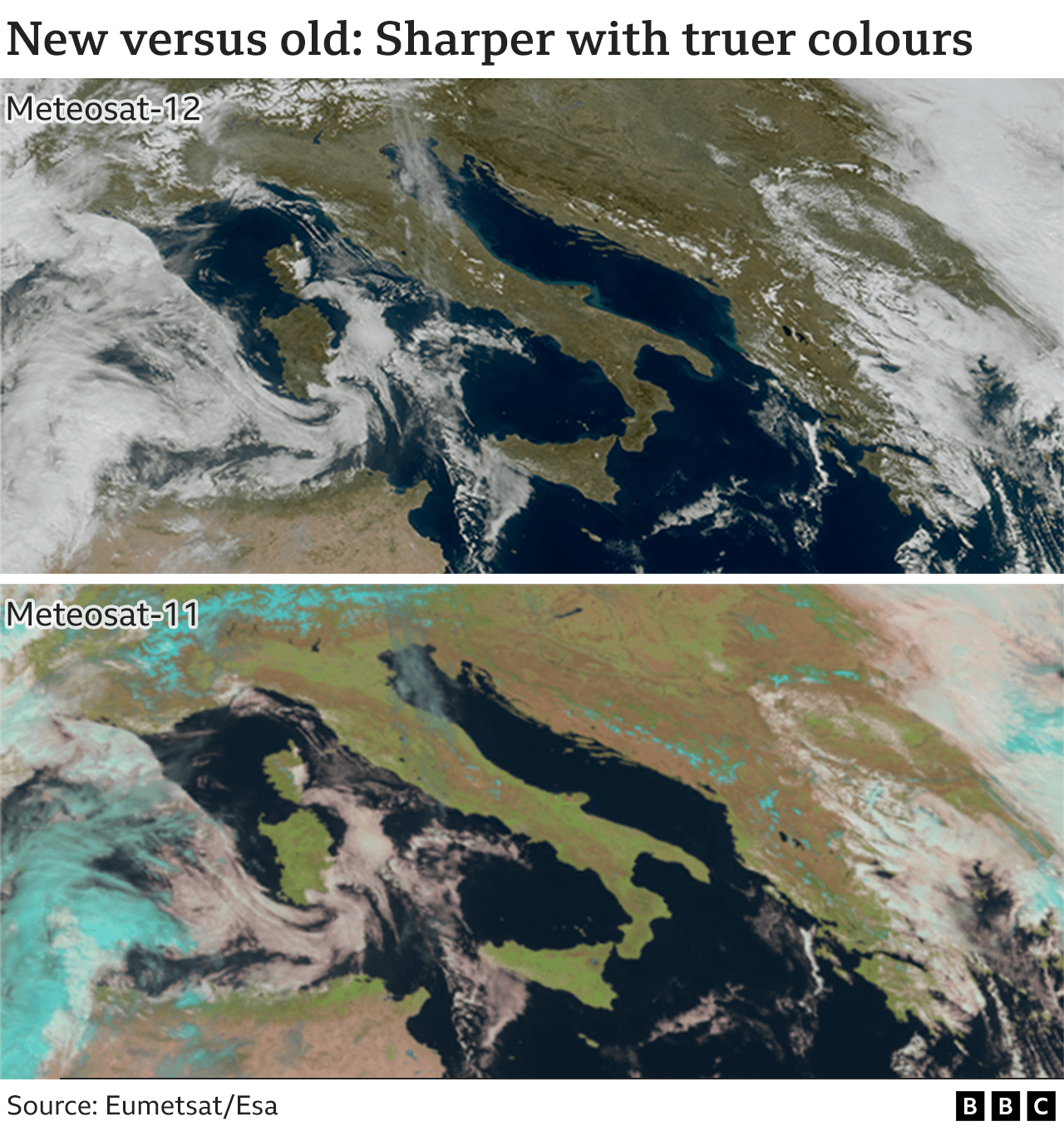

Part of this advance will come from the increased resolution of Meteosat-12. For previous generation satellites, a feature in a storm had to be at least 1km across to be detected. The new spacecraft will track features as small as 500m in diameter.

"We can now see very fine structures," said Jochen Grandell from Eumetsat, the intergovernmental agency that manages Europe's weather satellites.

"You may have heard the term 'overshooting top', for example, which is a part of a thunderstorm's cloud development where you might see very strong updrafts and downdrafts. These are very rapidly changing, and they are very small as well. But they are also very powerful," he told BBC News.

WATCH: European countries share the cost of running the Meteosat system

Europe has had its own meteorological spacecraft sitting high above the planet since 1977. The new imager is the third iteration in the series.

Meteosat-12 sits in a "stationary" position, keeping a permanent eye on Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

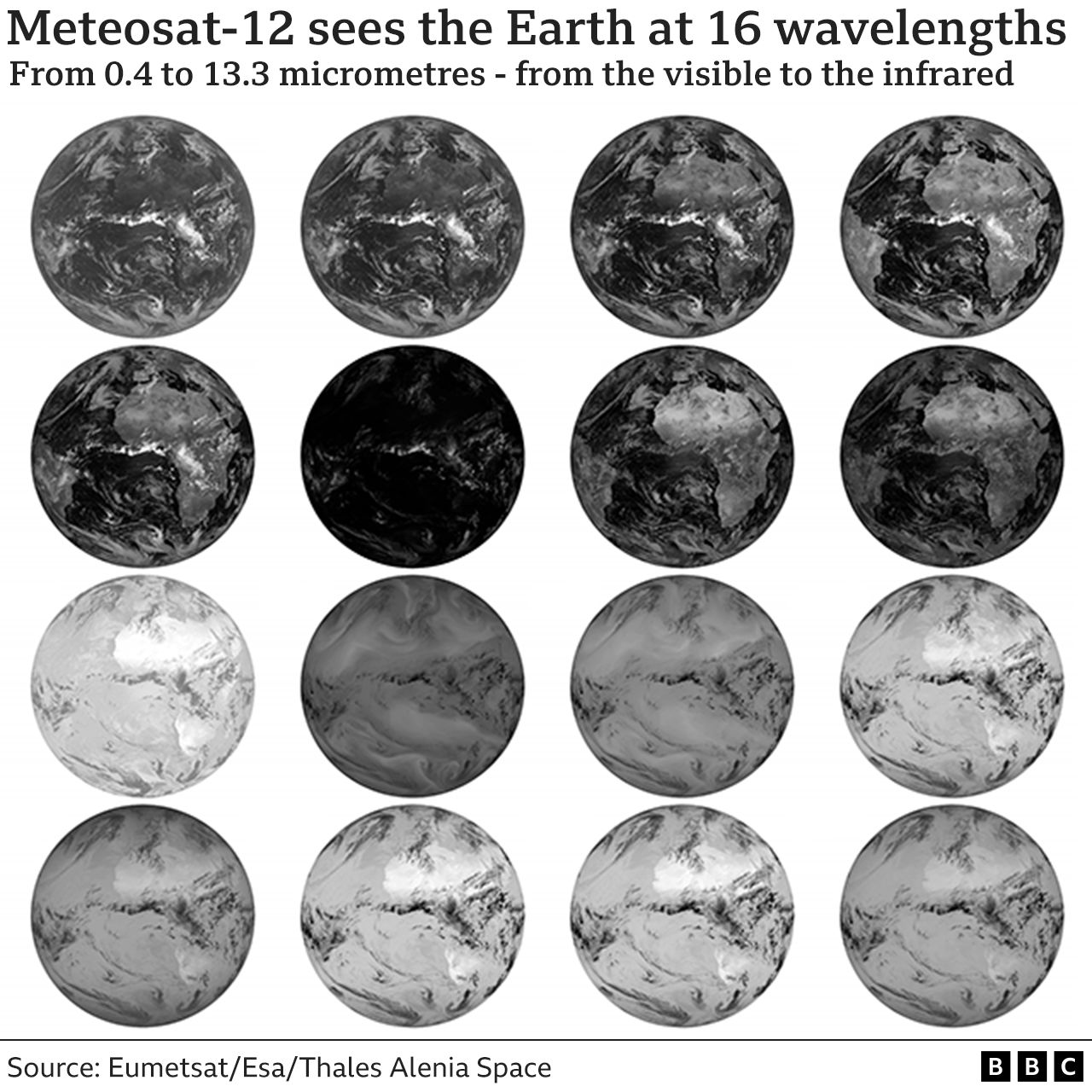

It will return a full picture of the weather systems racing across Earth's surface at a rate of one every 10 minutes, five minutes faster than has been the case up to now. It also views the planet in more wavelengths of light. Sixteen instead of the previously available 12.

The additional bands of light allow for true colour images. In other words, the pictures are much closer to what the human eye might perceive if looking down from the same vantage point.

"The first time we received the data, there were huge emotions because we could see the high quality of the sensor," recalled Eumetsat colleague Alessandro Burini.

"The optical quality of the images, of the radiometry, of the navigation - in other words the accuracy of the position of the individual pixels in an image - is really very good."

Artwork: The near-4 tonne satellite sits 36,000km above the equator

The new third-generation system will eventually comprise a trio of spacecraft working in unison.

A second imager will go up in 2026 to acquire more rapid - every 2.5 minutes - pictures of just Europe. Before that, in 2024, a "sounding" spacecraft will launch to sample the temperature and humidity down through the atmosphere.

With replacement satellites already ordered for the first working threesome, Europe is guaranteed coverage well into the 2040s.

The overall cost is expected to be about €4.3bn (£3.7bn).

If that sounds like a lot of money (and it is), it pales next to the value society accrues from accurate weather forecasting - in preventing loss of life, infrastructure damage and economic disruption.

Repeated analyses have judged the benefits to be worth tens of billions every year across Europe as a whole.

BBC Weather presenter and meteorologist Simon King was excited to see the new imagery.

"It's like going from standard definition to 4K," he said. "The increase in resolution is quite remarkable. When you zoom in you can really see the cloud structure. And it's not just cloud, you can see very clearly as well the dust in the atmosphere, which is important for hurricane development for example."

Nataša Strelec Mahović works at Eumetsat, training people how to use data from space. She's previously worked as a meteorologist in Croatia.

"Another example I would name as a consequence of higher resolution would be fog detection because we can now see fog even in very narrow valleys," she explained. "And maybe another application I would emphasize is wildfire monitoring, as [Meteosat-12] will not only see much smaller fires better and see the smoke, but the channels on [Meteosat-12] will allow us to see the differences even in fire intensity."

Testing of the satellite and ground systems will continue through this year. National forecasting agencies, such as the UK Met Office, Meteo France and DWD (the German Meteorological Service), should be ingesting Meteosat-12 information into their supercomputers on a routine basis early in 2024.