South rainier than north as UK weather trend flips

- Published

A wildfire burns on Scotland's Affric Kintail Way

The northern UK tends to be much wetter than the south, but this summer that pattern is being flipped on its head.

Water levels in much of Scotland are very low with some rivers breaking records, while southern England is mostly healthy after a very wet spring.

The UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology warns of increased risk of drought affecting farmers and nature.

One North Wales farmer told BBC News he has already almost lost a crop.

Meanwhile, experts at the Wildlife Trusts say they are seeing signs of stressed nature.

But current forecasts suggest the UK is unlikely to face drinking water shortages or hosepipe bans this summer.

However, "vigilance is still required" in the southeast after demand for water in the recent heatwave may have depleted supplies, explains Jamie Hannaford, UKCEH Group Leader for Hydrological Status and Outlooks.

Climate change is driving up global temperatures but there are currently no studies that clearly link human-induced climate change with altered risk of drought in the UK, according to the Met Office., external

UKCEH is an environmental research institute that analyses data from the Environment Agency and other public bodies.

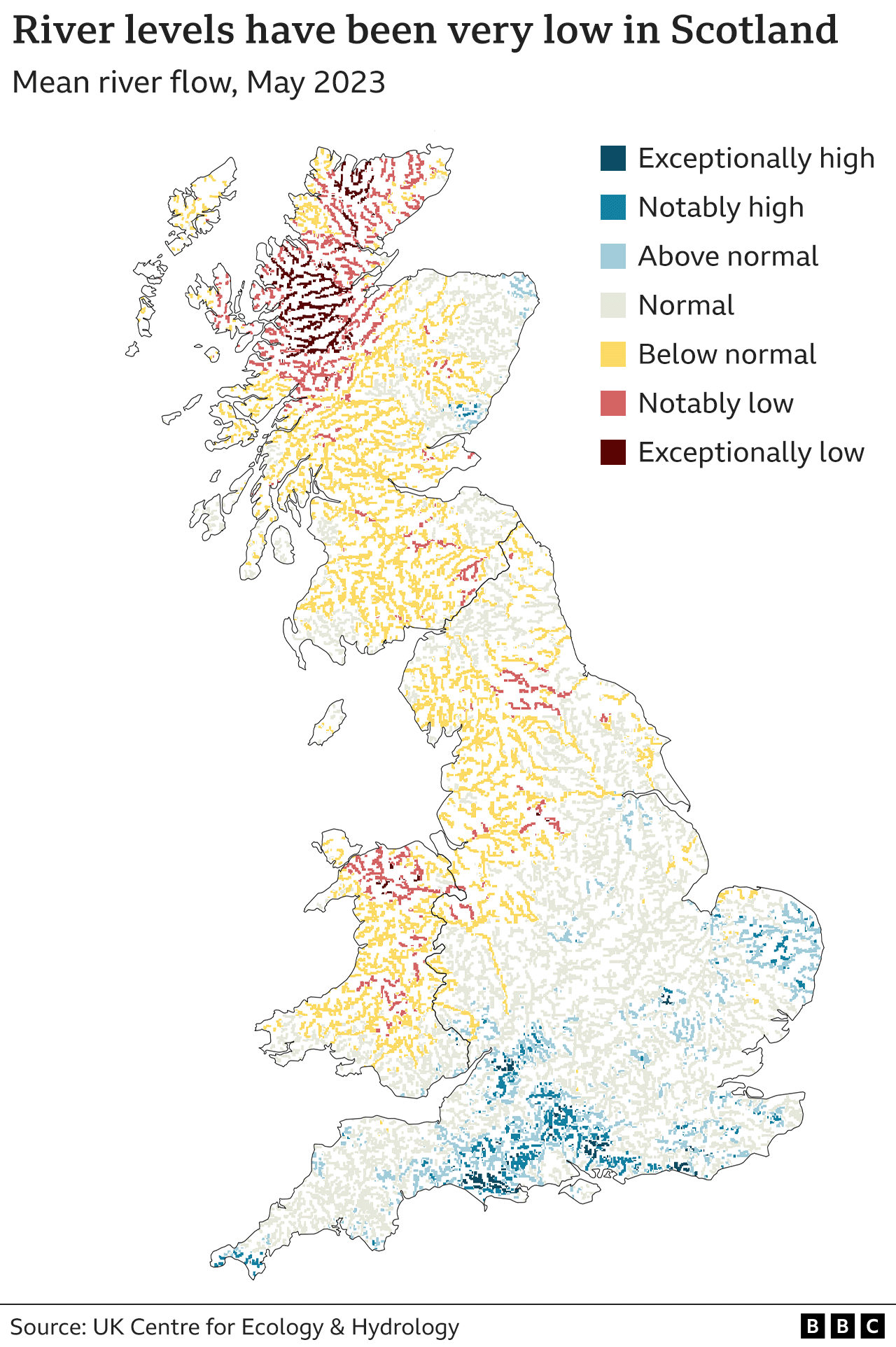

A map of UK river flows in May shows a clear divide between southern England and Wales, compared to Scotland, north-west England and north Wales.

The river Nevis in western Scotland registered its lowest May flow since records began in 1983, while the Ewe had its second lowest since 1971.

The Highlands had its eight driest May since 1890.

Last week the Scottish Environment Protection Agency issued water scarcity alerts for the majority of the country, external, with Loch Maree in the northwest highlands facing significant shortages.

By contrast, most southern regions received over 140% of their average rainfall. Wessex had its fifth wettest spring since records began there in 1890.

One exception is in Devon and Cornwall where hosepipe bans remain in place after drought last year affected reservoir levels.

The effects of dry weather are already being felt in parts of Scotland and Wales. A large wildfire burned overnight on Wednesday in the Rhondda valley, South Wales.

Last week firefighters in the Scottish Highlands fought to control what could be the UK's largest fire to date.

Helicopter footage shows large wildfire being fought on Rhigos mountain

Llŷr Jones, a farmer in Corwen, North Wales, has already noticed the effects of heat on his farm this year.

Temperatures in the sheds for his flock of 32,000 hens have consistently reached 28C for the past 10 days.

"We put in extra fans and encourage them to drink more water. They don't like anything higher than 25C so we're constantly checking to make sure they're happy," he says.

A field of spring barley planted in April was close to failure until thunderstorms on Monday rescued the crop, he explains.

"Last year, on this mountain in Wales, it reached 32C. You get to a point where there's nothing else you can do but desperately hope for rain to save the crops," he says.

He lives on the family farm with his wife and three young children, and says it's clear they will have to change how they farm.

"We are fully aware of the weather changing and we're doing everything we can to adapt," he explains.

The environment is already showing signs of drought, explains Ali Morse at The Wildlife Trusts.

"Vegetation is starting to look a bit drier, flowers aren't as healthy. If you look out at the countryside, it doesn't look as green," she explains.

But the "hidden impacts" of drought on wildlife are really concerning, she says, adding that there is some evidence that insect numbers are lower this year after the 2022 drought.

Butterflies and moths can be affected if they lay their eggs on plants that are dried out, or young fish may have stunted growth in rivers with low flows, affecting their ability to mate as adults.

"If we do avoid drought this year it was by chance, not because the UK did the right things to avoid it," she adds.

Data visualisation by Erwan Rivault