Titanic sub: Safety concerns raised about missing submersible

- Published

Watch: What debris has been found and what does it mean?

A former employee of OceanGate - the company that operates the missing Titan submersible - warned of potential safety problems with the vessel as far back as 2018.

US court documents show that David Lochridge, the company's Director of Marine Operations, had raised concerns in an inspection report.

The report "identified numerous issues that posed serious safety concerns", according to the documents, external, including the way the hull had been tested.

Mr Lochridge "stressed the potential danger to passengers of the Titan as the submersible reached extreme depths". He said his warnings were ignored and called a meeting with OceanGate bosses but was fired, according to the documents.

The company sued him for revealing confidential information, and he countersued for unfair dismissal. The lawsuit was later settled but we don't know the details of the settlement.

The BBC tried to contact Mr Lochridge but he is not commenting.

Separately, a letter sent to OceanGate by the Marine Technology Society (MTS) in March 2018 and obtained by the New York Times, external, stated "the current 'experimental' approach adopted by OceanGate... could result in negative outcomes (from minor to catastrophic)".

A spokesman for OceanGate declined to comment on the safety issues raised by Mr Lochridge and the MTS.

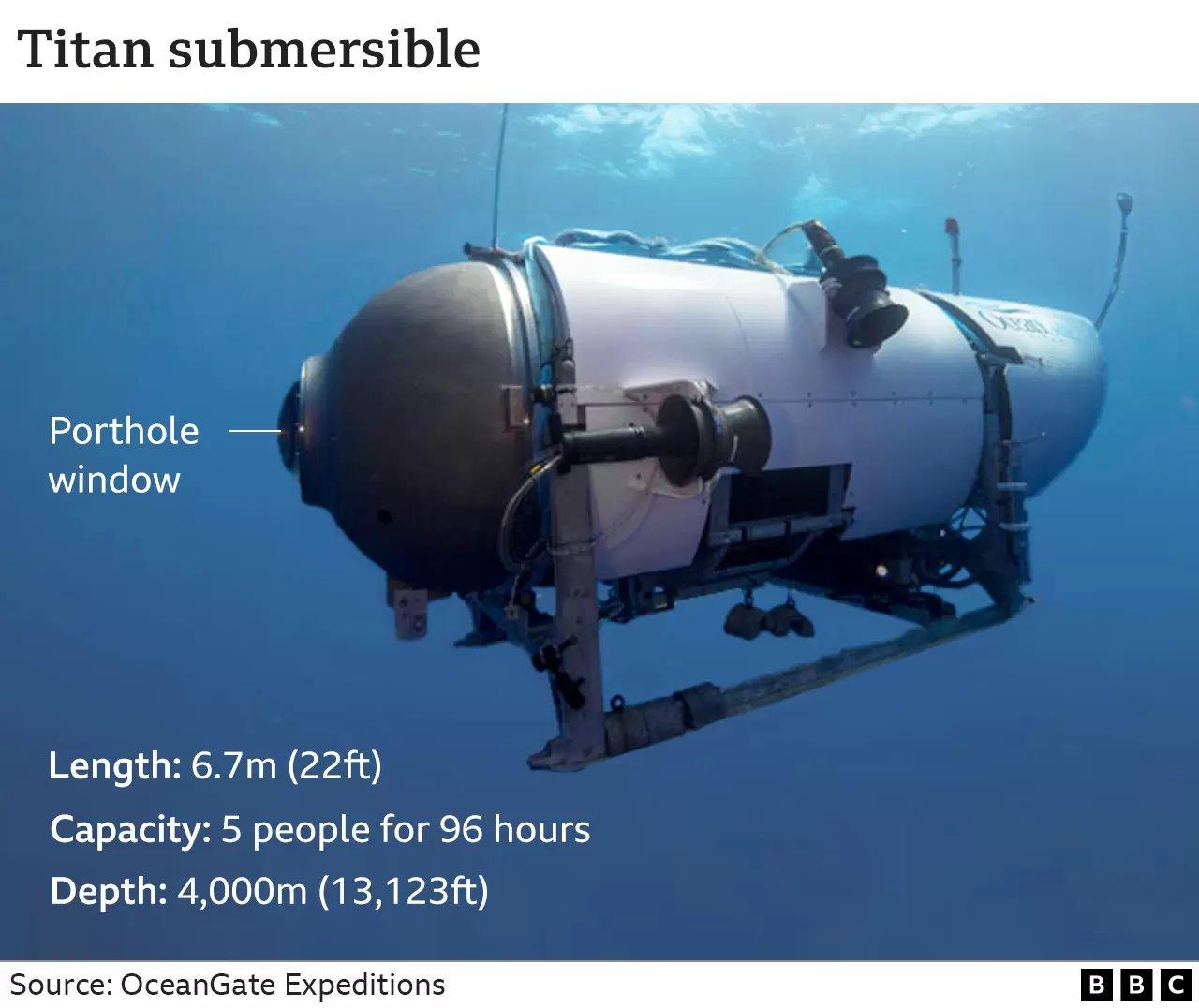

The Titan submersible, described as "experimental" by the company, was built from an unusual material for a deep sea vessel.

Its hull - surrounding the hollow part where passengers sit - was made from carbon fibre, with titanium end plates and a small window at one end.

"Typically, the part of deep-sea submersible housing the humans is a titanium sphere around 2m in diameter," said Dr Nicolai Roterdam, lecturer in marine biology at the University of Portsmouth.

To withstand the immense pressures of the deep you need super-strong materials, to resist the weight of water above that's pressing down on you.

Carbon fibre is cheaper than titanium or steel and is extremely strong, but it is largely untested for deep sea vessels like the Titan.

In an interview with Oceanographic, external last year, OceanGate's chief executive Stockton Rush said: "Carbon fibre is used successfully in yachts and in aviation, but it has not been used in crewed submersibles."

In the court documents, Mr Lochridge claimed the hull had not been properly tested - where it's placed under extreme pressures and analysed to look for potential problems.

He claimed that trials on a smaller scale model of the sub had revealed flaws in the carbon under pressure testing.

Mr Lochridge also raised the issue of the Titan's glass viewport. He claimed the company that made the material would only certify its use down to 1,300m.

More on the Titanic sub

A December 2018 statement from OceanGate, external said the Titan had completed a 4,000 meter dive which "completely validates OceanGate's innovative engineering and the construction of Titan's carbon fiber and titanium hull".

In a 2020 interview with GeekWire, external, Mr Rush said tests were conducted which revealed that the Titan's hull "showed signs of cyclic fatigue".

The BBC filmed Stockton Rush inside the submersible in 2022

In a May 2021 court filing, the company said Titan had undergone more than 50 test dives, including to the equivalent depth of the Titanic, in deep waters off the Bahamas and in a pressure chamber.

The shape of the Titan is also unusual.

The hull of a deep-diving sub is usually spherical, which means it receives an equal amount of pressure at every point, but Titan's hull is tube-shaped, so the pressure would not be equally distributed.

"Titan is quite a different deep-sea submersible compared to those used in research," said Dr Roterman.

"Whether or not this design with composite materials represents a structural weakness would be for engineers to determine, however," she added.

Why wasn't the sub certified?

In the court documents, Mr Lochridge also said he had urged OceanGate to get the submarine inspected and certified.

Subs can be certified or "classed" by marine organisations - for example by the American Bureau of Shipping (ABS) or DNV (a global accreditation organisation based in Norway) or Lloyd's Register.

This essentially means that the vehicle must meet certain standards on aspects including stability, strength, safety and performance.

The process involves reviewing the design and construction, assessing testing and trials to be certified. And once the sub is in service it needs to be checked periodically to ensure it still meets these criteria.

But certification of subs isn't mandatory.

OceanGate's Titan submersible (pictured above) has been missing since Monday

Titan was never certified or classed - as the company wrote a blog post about it in 2019., external

It said the way that Titan had been designed fell outside the accepted system - but it "does not mean that OceanGate does not meet standards where they apply."

It added that the classification agencies "slowed down innovation… bringing an outside entity up to speed on every innovation before it is put into real-world testing is anathema to rapid innovation".

A CBS reporter who went on the Titan in 2022 quoted a waiver people signed before boarding as stating it was "an experimental submersible vessel that has not been approved or certified by any regulatory body which could result in physical injury, emotional trauma or death."

Any sub that dives over 4,000m is a one-off vehicle - not something mass-produced - and requires innovation and novel design to survive at these depths.

But that doesn't mean this falls outside the classification system.

Take for example the sub called the Limiting Factor. This vessel, designed by Triton submarines, has repeatedly travelled to the very deepest places in the ocean - performing many dives to the bottom of the Mariana Trench, which lies 11km down.

It's a truly unique and cutting-edge vessel - but the team behind it collaborated with the DNV classification agency from design, through to construction and testing. And the Limiting Factor is fully certified to repeatedly - and safely - dive to any depth in the ocean.

Additional reporting by Thomas Spencer.

Sign up for our UK morning newsletter and get BBC News in your inbox.